10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/apl/a.14070

Artículos

Luis Felipe Dias Lopes 1

Deoclécio Junior Cardoso da Silva 2

Mauren Pimentel Lima 3

Beatriz Leite Gustmann Castro 4

Nuvea Kuhn 5

Fillipe Grando Lopes 6

Eduarda Grando Lopes 7

Luciano Amaral 8

Federal University of Santa Maria, Brazil

1  0000-0002-2438-0226, Ph. D. in Production Engineering, Research Professor of Administration

0000-0002-2438-0226, Ph. D. in Production Engineering, Research Professor of Administration

Declaration of interest statement: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Correspondence concerning

this article should be addressed to Luis Felipe Dias Lopes, Federal University

of Santa Maria, Av. Roraima n°. 1000, Cidade Universitária, Prédio 74C, Camobi, Santa Maria - RS, Brazil, CEP: 97105-900.

lflopes67@yahoo.com.br.

Phone: +55 (55) 999718584.

Received: march 18, 2024

Accepted: march 18, 2025

To cite this article: Lopes, L. F. D., Silva, D. J. C, Lima, M. P., Castro, B. L. G., Kuhn, N., Lopes, F. G., Lopes. E. G., & Amaral, L. (2024). Emotional health in the workplace: Validation of a measurement inventory. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, 42(3), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/apl/a.14070

Abstract

This study aimed to develop and validate the Emotional Health at Work Inventory (EHWI), a measurement tool designed to assess workers' emotional health in organizational settings. The research explored the factorial structure, reliability, and convergent validity of the EHWI, using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) as a reference for validation. A quantitative survey involving 483 workers from various professional sectors was conducted. Exploratory factor analysis and partial least squares structural equation modeling were employed to evaluate the instrument's psychometric properties. The results showed the validity and reliability of the EHWI, with positive emotions significantly associated with positive affect (P = 0.854, p < 0.001), and negative emotions strongly related to negative affect (P = 0.793, p < 0.001). Additionally, a negative relationship was found between positive and negative emotions (P = -0.290, p < 0.001). These findings suggest that the EHWI is an effective tool for assessing emotional health in the workplace, enabling organizations to systematically monitor employees' well-being. The study contributes to the field by providing an empirically validated measurement instrument that can guide interventions aimed at promoting positive emotional experiences and reducing negative emotional impacts in the workplace. Further research may explore cross-cultural adaptations and longitudinal applications of the EHWI.

Keywords: emotional health; workplace well-being; psychometric validation; positive emotions; negative emotions; structural equation modeling.

Resumen

Este estudio tuvo como objetivo desarrollar y validar el Inventario de Salud Emocional en el Trabajo (ISET), una herramienta de medición diseñada para evaluar la salud emocional de los trabajadores en entornos organizacionales. Se exploró la estructura factorial, confiabilidad y validez convergente del ISET, utilizando la Escala de Afecto Positivo y Negativo (PANAS) como referencia de validación. Se realizó una encuesta cuantitativa con 483 trabajadores de diversos sectores profesionales. Se aplicaron el análisis factorial exploratorio y el modelado de ecuaciones estructurales de mínimos cuadrados parciales para evaluar las propiedades psicométricas del instrumento. Los resultados confirmaron la validez y confiabilidad del ISET, con emociones positivas significativamente relacionadas con el afecto positivo (P = 0.854, p < 0.001) y emociones negativas fuertemente asociadas con el afecto negativo (P = 0.793, p < 0.001). Además, se observó una relación inversa entre emociones positivas y negativas (P = -0.290, p < 0.001). Estos hallazgos indican que el ISET es una herramienta eficaz para evaluar la salud emocional en el trabajo, que permite a las organizaciones monitorear sistemáticamente el bienestar de sus empleados. El estudio contribuye a este campo al ofrecer un instrumento validado empíricamente que puede guiar intervenciones para fomentar experiencias emocionales positivas y mitigar el impacto de emociones negativas en el entorno laboral. Investigaciones futuras pueden explorar adaptaciones transculturales y aplicaciones longitudinales del ISET.

Palabras clave: salud emocional; bienestar laboral; validación psicométrica; emociones positivas; emociones negativas; modelado de ecuaciones estructurales.

Resumo

Este estudo teve como objetivo desenvolver e validar o Inventário de Saúde Emocional no Trabalho (ISET), uma ferramenta de medição projetada para avaliar a saúde emocional de funcionários em ambientes organizacionais. A estrutura fatorial, a confiabilidade e a validade convergente do ISET foram exploradas usando a Escala de Afetos Positivos e Negativos (PANAS) como referência de validação. Foi realizada uma pesquisa quantitativa com 483 trabalhadores de diversos setores profissionais. A análise fatorial exploratória e a modelagem de equações estruturais de mínimos quadrados parciais foram aplicadas para avaliar as propriedades psicométricas do instrumento. Os resultados confirmaram a validade e a confiabilidade do ISET, com emoções positivas significativamente relacionadas ao afeto positivo (P = 0.854, p < 0.001) e emoções negativas fortemente associadas ao afeto negativo (P = 0.793, p < 0.001). Além disso, observou-se uma relação inversa entre emoções positivas e negativas (P = -0.290, p < 0.001). Essas descobertas indicam que o ISET é uma ferramenta eficaz para avaliar a saúde emocional no trabalho e isso permite que as organizações monitorem sistematicamente o bem-estar de seus funcionários. O estudo contribui para o campo ao oferecer um instrumento empiricamente validado que pode orientar intervenções para promover experiências emocionais positivas e mitigar o impacto das emoções negativas no ambiente de trabalho. Pesquisas futuras podem explorar adaptações transculturais e aplicações longitudinais do ISET.

Palavras-chave: saúde emocional; bem-estar no trabalho; validação psicométrica; emoções positivas; emoções negativas; modelagem de equações estruturais.

An individual's emotions play relevant roles in organizational environments, significantly influencing their interaction. Emotion is an affective state that causes physiological and endocrine changes in the individual, significantly influencing performance and shaping emotions, attitudes, and interests (López-Benítez et al., 2022).

Kumari (2012) reported that emotions are a dimension of health, being "a necessary condition to successfully manage one's life" (p. 48), involving expressing one's feelings in an age-appropriate way, controlling one's emotions and behaviors (Garnefski et al., 2001; Verzeletti et al., 2016). Thus, positive emotions are essential for overall health, particularly emotional well-being (Bacter et al., 2021; Lazarus, 2011).

Regarding emotions in the workplace, Dubreuil et al. (2021) explained that they influence employee performance. The authors analyzed the mediating role of positive and negative emotions in the relationship between strength use and work performance, demonstrating that these emotions influence this relationship.

Because of this, interest in the topic of emotional health in the workplace has grown. Emotional health is related to various psychological aspects, such as self-regulation, coping, perceived autonomy and control, and social skills (Bacter et al., 2021). For Ibikunle et al. (2021), workers' emotional health can serve as an indicator of satisfaction with both life and the workplace. Thus, the topic of emotional health has sparked much interest in research given that, according to Aliakbari (2015) and Ibikunle et al. (2021), the emotional health of individuals tends to influence work efficiency, performance, participation, absenteeism, and employee retention, thereby being an indicator of individual well-being.

Curry and Epley (2022) also investigated workers' emotional health. The authors reported that longevity in the workplace, supported by a new practice model, along with better satisfaction with the work environment, is associated to improved emotional health, helping to prevent burnout and employee turnover. Gorgenyi-Hegyes et al. (2021) showed that emotional health is closely related to well-being and happiness arising from recognition (i.e., social relationships in the work environment). Moreover, physical, and emotional health lead to well-being, although they do not affect worker loyalty in the workplace (Gorgenyi-Hegyes et al., 2021; Merino & Privado, 2015). According to Gorgenyi-Hegyes et al. (2021), the lack of a direct relationship between physical and emotional health and worker loyalty in the workplace may be influenced by factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as increased job insecurity and changes in work dynamics.

Considering the significance of emotional health in the workplace and its influence on employee performance, well-being, and loyalty, this study poses two research questions: (1) Can the development of an inventory focused on emotional health provide an accurate evaluation of workers? (2) Does the inventory of emotional health at work correlate with the dimensions of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)?

This study aimed to develop and validate the Emotional Health at Work Inventory (EHWI), examining its factorial structure, reliability, and convergent validity with the PANAS. Furthermore, this investigation aimed to assess the instrument's effectiveness in measuring workers' emotional health and provide insights for organizational interventions designed to enhance well-being in the workplace. As for the theoretical implications, this study may be an important contribution to the discussion on the application of the emotional health at work construct by validating the measurement instrument. Furthermore, we hope our findings will contribute to the problematization and debate on this topic and expand knowledge on this subject.

As practical implications, the results can subsidize and guide policies and programs to improve workers' well-being by providing a more detailed look at positive and negative emotions, work resources, organizational and social support, interpersonal relationships, personal resources, and work-life balance. Such a perspective is supported by Aung and Tewogbola (2019), Gupta (2019), and Alexander et al. (2020).

This study is structured as follows: after the introduction, the theoretical framework is presented, divided into emotional health at work and positive and negative emotions. In the third topic, the method is presented, demonstrating all the steps performed to develop this study, followed by the results in the fourth section and the discussion of the results. Finally, the study concludes with the final considerations.

Theoretical Background

Emotional Health in the Workplace

Emotional health is associated with lifestyle habits that promote a balanced psychological state, enabling individuals to manage emotions, maintain well-being, and prevent emotional disorders (Diener et al., 2019; Fredrickson, 2001). However, the absence of emotional disturbances does not necessarily equate to complete emotional health. Factors such as a lack of defined goals, emotional emptiness, and unchecked anxiety may create imbalances (Suh & Punnet, 2022).

In the workplace, emotions significantly influence organizational relationships (Dubreuil et al., 2021). Positive emotions can improve performance, engagement, and resilience, enhancing motivation and promoting employee social connections (Diener et al., 2019). Conversely, negative emotions might result in counterproductive work behaviors, decreased job satisfaction, and heightened emotional distress (Bauer & Spector, 2015; Nikolaev et al., 2019).

An established framework for emotional health within organizations can strengthen employee resilience, psychological well-being, and work-life balance. Conversely, negative workplace factors such as excessive workload, time pressure, poor interpersonal relationships, and unsupportive organizational culture can impair emotional health (Koinis et al., 2015; Marcucci & Santos, 2021).

Additionally, promoting positive emotions in professional settings encourages cooperative behaviors and mitigates workplace stress. Research has shown that recognition, appreciation, and gratitude significantly enhance employees psychological functioning and well-being (Di Fabio et al., 2017; Merino & Privado, 2015). Paakkanem et al. (2021) emphasized that acknowledging positive emotions among co-workers strengthens interpersonal relationships and empathy, contributing to a more supportive work environment.

Given these considerations, this study aims to investigate the role of emotional health in the workplace, evaluating its relationship with positive and negative effects through the following hypotheses:

• H1: Positive emotions are positively correlated with positive affect.

• H2: Negative emotions are positively correlated with negative affect.

• H3: Positive emotions are negatively correlated with negative emotions.

Positive and Negative Emotions in the Workplace

Positive emotions are associated with work performance, job satisfaction, and overall wellbeing, reinforcing employees' commitment and engagement (Fredrickson, 2001; Lyubomirsky et al., 2005). These emotions expand cognitive and behavioral flexibility, enabling individuals to navigate workplace challenges more effectively (Diener & Seligman, 2002; Fredrickson, 1998). Sansone and Sansone (2010) emphasized that gratitude enhances well-being, and in professional settings, promotes intrinsic motivation, job performance, and emotional stability (Armenta et al., 2017; Di Fabio et al., 2017).

In addition, workplace recognition and appreciation have a positive impact on employee engagement, reinforcing motivation and job satisfaction (Fagley, 2018); Merino & Privado, 2015). From a neurophysiological perspective, positive emotions contribute to psychological resilience and emotional health, improving employees' ability to manage stress and adapt to organizational changes (Alexander et al., 2021).

In contrast, negative emotions in the workplace are associated with stress, burnout, and reduced job satisfaction (Nikolaev et al., 2019). Such emotions, including anger and anxiety, can lead to dissatisfaction and negatively impact the organizational climate (Gross, 2015; Katana et al., 2019; Madrid et al., 2015). Bauer and Spector (2015) showed that experiencing negative emotions in the workplace increases counterproductive behaviors, while Leung and Lee (2014) found that guilt and shame contribute to emotional distress and reduced motivation.

Furthermore, neuroscience studies suggest that emotions are processed through two mechanisms: one linked to reward and positive experiences (e.g., satisfaction, pleasure, and joy) and another associated with punishment and negative emotional responses (e.g., sadness, frustration, and stress) (Balestrin & De Marco, 2019). Fisher (2019) argued that negative emotions have a greater impact in the workplace, as they tend to trigger stressful and conflict-prone situations more often than positive emotions.

However, researchers have suggested that positive emotions counteract the effects of negative emotions, promoting emotional regulation and resilience (Gupta, 2019). Silvestre and Vandenberghe (2013) highlighted that positive emotions reduce stress and enhance interpersonal relationships, cognitive flexibility, and coping strategies. Employees who consistently experience positive emotions report higher well-being, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment (Alexandre et al., 2021; Diener & Seligman, 2002).

Colombo et al. (2021) also that mindfulness and gratitude-based strategies significantly improve emotional regulation. These findings underscore the importance of developing and implementing workplace interventions that promote positive emotions and emotional intelligence to enhance well-being and productivity.

This study establishes a clear relationship between emotional health and workplace affect, aiming to provide organizations with a structured assessment tool to evaluate and foster employee well-being. The hypotheses, based on psychological and organizational behavior research, provide a foundation for future workplace interventions aimed at enhancing emotional health and professional performance.

Method

In order to achieve the defined objective, this study was designed with a descriptive and quantitative approach and a population composed of workers from various segments (teachers, health professionals, police officers, and civil servants, among others) of different regions in Brazil. The respondents were contacted via email and social networks and were provided with an online questionnaire along with a free informed consent form. If they agreed to participate, they proceeded to answer the questionnaire. The data were collected from March to April 2022, ensuring an acceptable, representative, and reliable sample for proposing the model and analyzing the results. Thus, 483 valid responses were obtained using the convenience sampling method. The inclusion criteria consisted of being at least 18 years old and being formally employed. To comply with the ethical precepts, this study was approved by an ethics committee (CAAE 44261821.8.0000.5346, opinion CEPE 4.606.946).

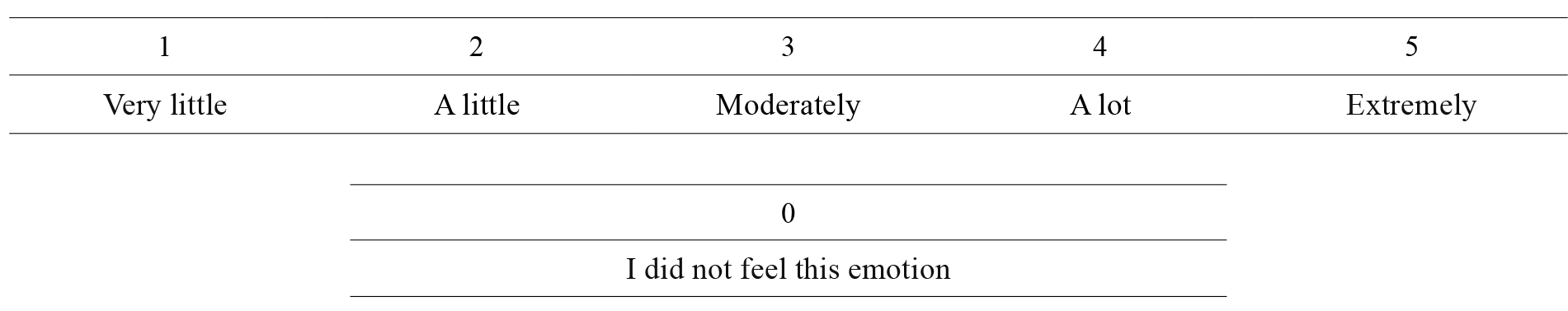

In order to evaluate emotional health, the EHWI (Appendix) was developed. It is composed of two dimensions: one positive dimension containing ten different types of emotions (Joy/Happiness, Love, Kindness, Satisfaction, Fun, Affection, Gratitude, Humor, Motivation, and Pleasure) and the other negative dimension containing ten emotions (Anxiety, Discouragement, Frustration, Regret, Fear, Bitterness, Rage, Anger, Boredom, and Stress). The individuals answered their emotions felt during the last two weeks of work using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ("very little") to 5 ("extremely"), with the possibility of answering "I did not feel this emotion" (score of 0).

In order to verify the effectiveness of the developed instrument and improve its credibility, the EHWI was related to the PANAS proposed by Watson et al. (1988) and validated for Brazil by Nunes et al. (2019). This scale is composed of two dimensions containing ten positive affect items (Interested, Enthusiastic, Excited, Nice, Determined, Proud, Active, Charmed, Warm, and Surprised) and ten negative affect items (Disturbed, Tormented, Afraid, Scared, Nervous, Tremulous, Remorse, Guilty, Irritable, and Repulsive), which was answered using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ("very little or not at all") to 5 ("Extremely"). The participants' demographic information was also collected, including gender, age group, marital status, and region of residence.

Data Analysis

The data were imported into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (version 365) and analyzed by the SPPS® Software (version 26) and SmartPLS® version 4.1.0.9. The data were presented in tables and graphs expressed in absolute values and percentages and the instrument validation statistics.

First, construct validation was applied using the exploratory factor analysis method for positive and negative emotions to verify the relationship between indicators and dimensions (factor loadings). Subsequently, the partial least squares structural equational modeling (PLS-SEM) method was applied to estimate the relationships between the dimensions of the EHW Inventory and the PANAS by assessing the convergent validity of the proposed scale. To rank the dimensions of the instruments, the score standardization technique (Equation 1) was applied to make the dimensions of the scales comparable (Lopes, 2018). A score of 0.00 to 33.33 is classified as low, 33.34 to 66.67 as moderate, and 66.68 to 100 as high.

Where:

Ssi = standardized score for dimension I.

Sum = sum of valid scores for dimension I.

Minimum = lowest possible score for dimension I.

Maximum = highest possible score for dimension i.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

The demographic and social data, including the Brazilian region where they work (work or study), gender, age group, and marital status, are listed in Table 1. Of the 483 respondents, 367 (67.09 %) live in southern Brazil, 275 (56.94 %) are male, 214 (44.31 %) are adults up to 30 years old, and 263 (54.45 %) are not married (single, separated, or widowed).

Table 1 Statistical details of respondents' demographic and social characteristics

Note: n = number of individuals; % = percentage.

Consistency of the Instrument and Model Fit

The path model was fitted for 300 iterations, but stabilized after 7 iterations. The bootstraping technique was used for 5.000 subsamples, and the predictive relevance criterion of the model was determined by the blindfolding technique. The model stabilized after seven iterations, and the model fit was determined by standardized root mean square residuals (SRMR), square euclidean distance (SED), geodesic distance (Gd), and the normed fit index (NFI). The results confirmed that the proposed structural model fit the data with acceptable indices (SRMR = 0.073, SED = 7.135, Gd = 1.718, NFI = 0.812). The SRMR value was below 0.08 and the NFI value was above 0.8 (Henseler et al., 2016), indicating a satisfactory and adequate structural model.

Correlation, Multicollinearity, and Descriptive Assessment of Dimensions

The values of the correlations between the dimensions and their significance are shown in Figure 1. The highest correlation was between negative emotions (NE) and negative affect (NA) (r = 0.693) and positive emotion (PE) and positive affect (PA) (r = 0.654), while the lowest correlation was between PA and NA (r = -0.174). We observed that all correlations were significant and, according to Hair et al. (2019), were acceptable and did not compromise the structural model. Another relevant aspect concerns the dispersions: the positive emotions with positive affect and the negative emotions with negative affect. For the descriptive evaluation (Table 2), the mean and the standard deviation of the dimensions were calculated, and the mean values ranged from 2.01 to 2.78. Standard deviation values ranged from 0.903 to 0.995, showing that the means were representative for eachNof the dimensions.

Figure 1. Pearson correlation matrix and descriptive statistics

Table 2 Factorial loadings, VIF, reliability, and average extracted variance

Measurement Model Assessment

The factorial loadings, variance inflation factor (VIF) values for assessing the interrelationships between observed variables and their respective latent variables, as well as Cronbach's alpha, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR) are listed in Table 2. The VIF values ranged from 1.290 to 3.860, meeting the criterion of non-collinearity (i.e., VIF < 5.0) (Joseph et al., 2010), while the alpha and CR values met the assumptions (0.7 < 0 < 0.95). Lastly, the AVE proposed by Hair et al. (2022) was also met (AVE > 0.5). The alpha of the PA was higher than the original scale 0.926 > 0.840, and the NA was lower than the original scale 0.894 < 0.90.

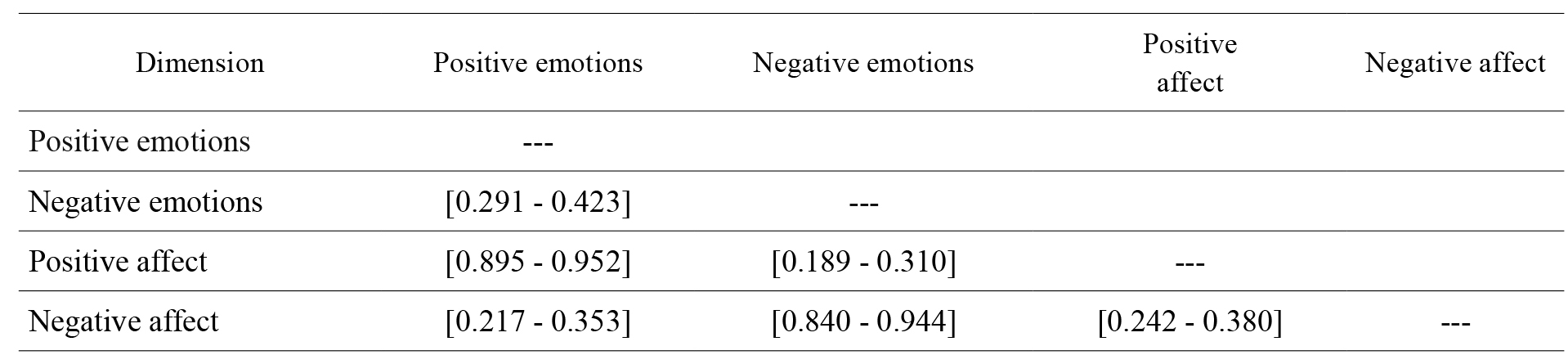

As for the discriminant validity of the model, the model was tested by the Heterotrait Monotrait Ratio (HTMT), as it provides the true estimate of the correlations between the dimensions and, therefore, better control of the relevance and accuracy of the proposed model (Henseler, 2011; Henseler et al., 2015). The HTMT values were excellent, as the upper limit of the HTMT for the 95 % confidence interval, calculated using the bootstrapping method, was below 1. The values found were between 0.310 and 0.952, which are considered acceptable for the discriminant validity of the model (Hair et al., 2022) (Table 3).

Table 3 Discriminant validity of the model by HTMT criterion*

Note. * 95% confidence interval.

Structural Model Assessment

To evaluate the coefficients of explanation, a structural model analysis was used with PLS-SEM using bootstrapping techniques (5.000 subsamples) (Hair et al., 2022). The blindfolding technique was used to evaluate the predictive relevance of the model (Geisser, 1975; Stone, 1974). The path coefficients/hypotheses were analyzed by the Student t-test (Hair et al., 2022) (Table 4).

Table 4 The relationship analysis through PLS-SEM and evaluation of model coefficients

By analyzing the coefficients of explanation, a statistical significance was observed in the three predictive dimensions, highlighting that PE explained 72.9 % of PA and NE explained 62.9 % of NA. The same occurred with the predictive relevance PE — PA (Q2 = 0.434) and NE — NA (Q2 = 0.317.). Positive relationships were observed between PE — PA (p = 0.854; t = 6.024; p = 0.000) and NE — NA (p = 0.793; t = 3.246; p = 0.000) and negative relationship between PE - NE (p = -0.290; t = 5.889; p = 0.000) (Table 4).

Figure 2 shows the descriptive measures of the indicators for each dimension. The highest positive emotion of the respondents was Gratitude (mean = 3.31; SD = 1.193), which is a reflection of having survived a pandemic, having gone through difficult times, and having expectations for better days, while the lowest was Kindness (2.37; 1.053). This reflects the lack of affection, little affection, and lack of care due to social confinement. The highest negative emotion was Stress (2.69; 1.247), which is a reflection of the moment of concern we are living due to physical and emotional overload. The lowest was Bitterness (1.63; 0.773), reflecting the extent to which people relied on each other during the pandemic to offer help and foster a sense of hospitality. As for the affections, we observed that the highest positive affect was Active (3.08; 1.255), which arises from the principle of people wanting to be effective, diligent, and resilient. The lowest positive affect was Excited (2.27; 1.029), that is, less excited and stimulated to perform tasks. The highest negative affect was Nervous (2.60; 1.181), which means feeling upset, distressed, and impatient with the situation we live. The lowest affect was Remorse (1.62; 0.717), less guilty and distressed.

Figure 2. Descriptive measure of emotion and affect indicators (mean)

Figure 3 shows that both positive (60.04 %) and negative (47.41 %) emotions predominated in a moderate index in the individuals surveyed. In contrast, 66.29 % of the individuals surveyed exhibited a high level of negative affect, while 53.83 % demonstrated moderate positive affect.

Figure 3. Classification of dimensions

Discussion

Experiencing positive emotions is crucial for well-being in the workplace, influencing employee engagement, performance, and resilience (Diener et al., 2019). In this study, "Gratitude" emerged as the most intense positive emotion (3.31; 1.193), associated with feelings of recognition and value, while "Kindness" was the least intense (2.37; 1.153), associated with care, affection, and appreciation. Research indicates that gratitude in the workplace significantly enhances employee well-being and job satisfaction. Di Fabio et al. (2017) found that employees who experience gratitude are more likely to cultivate positive emotions, contributing to improved psychological health. Armenta et al. (2017) noted that gratitude boosts motivation, leading to prosocial behaviors and stronger commitment to organizational goals. Trépanier et al. (2015) found that recognition positively affects employees' psychological functioning, and Fagley (2018) identified appreciation as a crucial factor in promoting well-being at work through positive emotions.

Concerning negative emotions, "stress" was identified as the most intense (Figure 3), associated with anxiety, worry, and nervousness. While stress can enhance focus and energy via adrenaline release (Matthews et al., 1990), it can harm employees' mental health. "Bitterness," associated with irritation, anger, and resentment, was the least intense negative emotion. These findings concur with Magiolino (2014), who argued that such emotions are often seen negatively in the workplace, prompting coping mechanisms such as avoidance or suppression. Nevertheless, Magiolino (2014) suggested that workplace interventions should concentrate on emotion regulation strategies to improve employees' capability to effectively navigate workplace challenges.

Hypothesis Testing and Workplace Implications

H1: Positive emotions are positively correlated to positive affect. This hypothesis was confirmed, aligning with Silton et al. (2020), who found that positive emotions at work are closely related to well-being and motivation. Alexander et al. (2021) further highlighted that experiencing positive emotions promotes happiness and engagement in professional settings.

H2: Negative emotions are positively correlated to negative affect. This hypothesis was also supported. Research indicates that negative emotions can contribute to stress and burnout, impacting employees' emotional health (Kang & Nan, 2022). Fadardi and Azadi (2017) and Almaraz et al. (2022) discovered that workplace emotional health could be influenced by personal beliefs, including religious faith, which may mitigate some negative effects but not eliminate their impact on well-being. Thus, mindfulness-based training and emotional intelligence programs are recommended to improve emotional self-regulation and minimize negative emotions in professional environments (Kang & Nan, 2022).

H3: Positive emotions are negatively correlated to negative emotions. This hypothesis was supported, albeit with a weak correlation. Studies suggest that positive emotions can counteract negative emotions by broadening individuals' cognitive and behavioral capabilities (Diener & Seligman, 2002; Gupta, 2019; Pressman et al., 2019). In work settings, emotions such as joy and gratitude can enhance collaboration, creativity, and engagement, while reducing the effects of stress and anxiety (Gupta, 2019; Johnson et al., 2020). Fredrickson (2001) posited that positive emotions widen cognitive flexibility and enhance adaptive behaviors, enabling employees to navigate challenges more effectively. Fredrickson (2004) showed that experiencing positive emotions in the workplace can reduce the aftereffects of stress and frustration, although the underlying mechanisms remain to be clarified.

Implications for Workplace Emotional Health

In work environments, positive and negative emotions influence decision-making, teamwork, and overall job satisfaction (Johnson et al., 2020; MacIntyre & Vincze, 2017). While negative emotions can serve adaptive purposes, such as alerting employees to potential threats or conflicts, excessive negativity in the workplace can lead to disengagement and burnout. Consequently, fostering a culture of psychological safety, recognition, and emotional intelligence training can help organizations enhance employee well-being and productivity.'Positive emotions have the potential to neutralize negative emotional experiences by expanding employees' thought-action repertoire, reducing emotional exhaustion and fostering resilience in the workplace (Fredrickson, 2001; Johnson et al., 2020). This highlights the significance of developing emotional health inventories tailored to professional contexts, enabling organizations to effectively assess, monitor, and improve employees' emotional well-being.

Final considerations

This article aimed to propose an inventory of emotional health at work, testing the relationship between the proposed inventory and the dimensions of the PANAS to demonstrate its validity. Based on the analysis results, the proposed inventory was validated, demonstrating reliability in the statistical tests (see Table 3).

Based on the measurements taken from the surveyed population, gratitude emerged as the prominent positive emotion, while stress was the most prominent negative emotion. Authors such as Cain et al. (2019) make it clear that gratitude in the work environment can be pivotal to well-being, as it can be understood as an individual's positive tendency to recognize and correspond to positive events, thus improving work performance (Cortini et al., 2019).

By relating the dimensions of the proposed instrument with the PANAS, we observed that the hypotheses tested were supported, thus demonstrating validity and reliability for the inventory to assess emotional health at work.

Based on the empirical and theoretical evidence discussed, it is possible to conclude that the argument that the EHWI provides a coherent and reliable assessment of employees' emotional health. Thus, the theoretical implications lie in the fact that it develops, validates, and presents an instrument to assess the emotional health of employees in the workplace, thus generating empirical information that can help other researchers to develop studies on the subject. Moreover, the managerial implications lie in the dynamism and ease with which managers can interpret the results, providing evidence that can support decision-making and strategy formulation for addressing negative emotions that may significantly impact employee performance and, consequently, the organization.

As a limitation of this stud is the challenge of retrieving the applied instruments and the restricted sample population. Future studies should apply the instruments to workers from specific sectors and a larger population, as well as analyze its relationship with other instruments documented in the literature.

References

Alexander R., Aragón O. R., Bookwala J., Cherbuin N., Gatt J. M., Kahrilas I. J., Kàstner N., Lawrence A., Lowe L., Morrison R. G., Mueller S. C., Nusslock, R., Papadelis, C., Palnaszek, K. L., Richter, S. H., Silton, R. L., & Styliadis, C. (2021). The neuroscience of positive emotions and affect: Implications for cultivating happiness and wellbeing. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 121, 220-249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.12.002

Aliakbari, A. (2015). The impact of job satisfaction on teachers' mental health: A case study of the teachers of Iranian Mazandaran province. World Scientific News, 12, 1-11. https://worldscientificnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/WSN-12-2015-1-11.pdf

Almaraz, D., Saiz, J., Moreno Martín, F., Sánchez-Iglesias, I., Molina, A. J., Goldsby, T. L., & Rosmarin, D. H. (2022). Religiosity, emotions and health: The role of trust/mistrust in god in people affected by cancer. Healthcare, 10(6), Article 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10061138

Armenta, C. N., Fritz, M. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2017). Functions of positive emotions: Gratitude as a motivator of self-improvement and positive change. Emotion Review, 9(3), 183-190. http://doi.org/10.1177/1754073916669596

Aung, N., & Tewogbola, P. (2019). The impact of emotional labor on the health in the workplace: A narrative review of literature from 2013-2018. AIMS Public Health, 6(3), 268-275. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2019.3.268

Bacter, C., Bãltãtescu, S., Marc, C., Sãveanu, S., & Buhas, R. (2021). Correlates of preadolescent emotional health in 18 countries. A study using children's words data. Child Indicators Research, 14(4), 1703-1722. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12187-021-09819-y

Bauer, J. A., & Spector, P. E. (2015). Discrete negative emotions and counterproductive work behavior. Human Performance, 28(4), 307-331. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2015.1021040

Balestrin, J. L., & De Marco, T. T. (2019). Emoções com base na neurociência e a sua ligação com os transtornos de ansiedade: uma contribuição para a área da psicologia. Anuário Pesquisa e Extensão Unoesc Videira, 4, Article e23386. https://portalperiodicos.unoesc.edu.br/apeuv/article/view/23386.

Cain, I. H., Cairo, A., Duffy, M., Meli, L., Rye, M. S., & Worthington Jr., E. L. (2019). Measuring gratitude at work. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(4), 440-451. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1484936.

Cortini, M., Converso, D., Galanti, T., Di Fiore, T., Di Domenico, A., & Fantinelli, S. (2019). Gratitude at work works! A mix-method study on different dimensions of gratitude, job satisfaction, and job performance. Sustainability, 11 (14), 3902. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143902

Colombo, D., Pavani, J. B., Fernández-Álvarez, J., García-Palacios, A., & Botella, C. (2021). Savoring the present: The reciprocal influence between positive emotions and positive emotion regulation in everyday life. PLoS One, 16(5), Article e0251561. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251561.

Curry, A., & Epley, P. (2022). "It makes you a healthier professional": The impact of reflective practice on emerging clinicians' self-care. Journal of Social Work Education, 58(2), 291-307. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2020.1817825.

Di Fabio, A., Palazzeschi, L., & Bucci, O. (2017). Gratitude in organizations: A contribution for healthy organizational contexts. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Article 2025. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02025

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81-84. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00415

Diener, E., Thapa, S., & Tay, L. (2019). Positive emotions at work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 7(1), 451-477. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012119-044908

Dubreuil, P., Ben Mansour, J., Forest, J., Courcy, F., & Fernet, C. (2021). Strengths use at work: Positive and negative emotions as key processes explaining work performance. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l 'Administration, 38(2), 150-161. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1595.

Fadardi, J. S., & Azadi, Z. (2017). The relationship between trust-in-God, positive and negative affect, and hope. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(3), 796-806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-015-0134-2.

Fagley, N. S. (2018). Appreciation (including gratitude) and affective well-being: Appreciation predicts positive and negative affect above the Big Five personality factors and demographics. SAGE Open, 8(4), 215824401881862. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018818621.

Fisher, C. (2019). Emotions in organizations. In R. J. Aldag (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopedia of business and management. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acre-fore/9780190224851.013.160

Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 300-319. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.23.300.

Fredrickson B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broadenand-build theory of positive emotions. The American Psychologist, 56(3), 218-226. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.218.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367-1377. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1512.

Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V., & Spinhoven, P. (2001). Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personality and Individual Differences, 30(8), 1311-1327. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00113-6

Geisser, S. (1975). The predictive sample reuse method with applications. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 70(350), 320-328. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01621459.1975.10479865

Gorgenyi-Hegyes, E., Nathan, R. J., & Fekete-Farkas, M. (2021). Workplace health promotion, employee wellbeing and loyalty during COVID-19 pandemic - Large scale empirical evidence from Hungary. Economies, 9(2), Article 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9020055.

Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781

Gupta, R. (2019). Positive emotions have a unique capacity to capture attention. Progress in Brain Research, 247, 23-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.pbr.2019.02.001

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). A Primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E, (2019). Multivariate data analysis. Cengage Learning.

Henseler, J. (2011). Why generalized structured component analysis is not universally preferable to structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 402-413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0298-6.

Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2-20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115-135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Ibikunle, M. A., Afolabi, R. F., & Bello, S. (2021). Job Satisfaction and Psychological Distress among Teachers in Selected Schools in Ibadan, Southwestern Nigeria in 2021: A Cross-Sectional Study. Journal of Occupational Health and Epidemiology, 10(4), 266-273. http://johe.rums.ac.ir/article-1-500-en.html

Johnson, S. L., Elliott, M. V., & Carver, C. S. (2020). Impulsive responses to positive and negative emotions: Parallel neurocognitive correlates and their implications. Biological Psychiatry, 87(4), 338-349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.08.018

Joseph, F., Barry, J. B., Rolph, E. A., & Rolph, E. A. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson Prentice Hall.

Kang, M. Y., & Nan, J. K. M. (2022). Effects and mechanisms of an online short-term audio-based mindfulness program on negative emotions in a community setting: A study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Integrative Medicine, 52, 102139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2022.102139

Katana, M., Rõcke, C., Spain, S. M., & Allemand, M. (2019). Emotion regulation, subjective wellbeing, and perceived stress in daily life of geriatric nurses. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, Article 1097. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01097

Koinis, A., Giannou, V., Drantaki, V., Angelaina, S, Stratou, E., & Saridi, M. (2015). The impact of healthcare workers job environment on their mental-emotional health. Coping strategies: The case of a local general hospital. Health Psychology Research, 3(1), Article 1984. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4768542/

Kumari, P. L. (2012). Influencing factors of mental health of adolescents at school level. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 5, 48-56. https://iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/papers/Vol5-issue4/G0544856.pdf

Lazarus, R. S. (2011). Emotie si adaptare: o abordare cognitiva a proceselor afective [Emotion and adaptation. A cognitive approach to affective processes]. Editura Trei.

Leung, S., & Lee, A. (2014). Negative affect. In A. C. Michalos (Ed.), Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0753-5_1923

Lopes, L. F. D. (2018). Métodos quantitativos aplicados ao comportamento organizacional [electronic resource]. Voix, https://www.gpcet.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/E-book.pdf

López-Benítez, R., Carretero-Dios, H., Lupiáñez, J., & Acosta, A. (2022). Influence of emotion regulation on affective state: Moderation by trait cheerfulness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23, 303-305, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00400-6

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 803-855. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803

MacIntyre, P. D., & Vincze, L. (2017). Positive and negative emotions underlie motivation for L2 learning. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 7(1), 61-88. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2017.7.1.4

Madrid, H. P., Patterson, M. G., & Leiva, P. I. (2015). Negative core affect and employee silence: how differences in activation, cognitive rumination, and problem-solving demands matter. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100, 1887-1898. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039380

Magiolino, L. L. S. (2014). A significação das emoções no processo de organização dramática do psiquismo e na constituição social do sujeito. Psicologia e Sociedade, 26, 48-59. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-71822014000600006

Marcucci, L., & Santos, R. C. (2021). The impact of absenteeism and the relationship with emotional absence based on individual stories. Independent Journal of Management & Production, 12(4), 945-963. https://doi.org/10.14807/ijmp.v12i4.1351

Matthews, D. E., Pesola, G., & Campbell, R. G. (1990). Effect of epinephrine on amino acid and energy metabolism in humans. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, 258(6), E948-E956. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.1990.258.6.e9

Merino, M. D., & Privado, J. (2015). Does employee recognition affect positive psychological functioning and well-being? The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 18. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2015.67

Nikolaev, B., Shir, N., & Wiklund, J. (2019). Dispositional positive and negative affect and self-employment transitions: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 44(3), 451-474. http://doi.org/10.1177/1042258718818357

Nunes, L. K. O., Lemos, D. C. L., Ribas, R. C., Behar C. B., & Santos, P. P. P. (2019). Análise psico-métrica da PANAS no Brasil. Ciencias Psicológicas, 13(1), 45-55. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v13i1.1808

Paakkanem, M. A., Martela, F., & Pessi, A. B. (2021). Responding to positive emotions at work - The Four Steps and potential benefits of a validating response to coworkers' positive experiences. Frontiers in Psychology, 11 (12), Article 668160. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.668160

Pressman, S. D., Jenkins, B. N., & Moskowitz, J. T., (2019). Positive affect and health: What do we know and where next should we go? Annual Review of Psychology, 70(1), 627-650. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102955

Sansone, R. A., & Sansone, L. A. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: the benefits of appreciation. Psychiatry (Edgmont), 7(11), 18-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21191529/

Silvestre, R. L. S., & Vandenberghe, L. (2013). Os benefícios das emoções positivas. Contextos Clínicos, 6(1), 50-57. https://doi.org/10.4013/ctc.2013.61.06

Silton, R. L., Kahrilas, I. J., Skymba, H. V., Smith, J., & Bryant, F. B., & Heller, W. (2020). Regulating positive emotions: implications for promoting well-being in individuals with depression. Emotion, 20(1), 93-97. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000675

Stone, M. (1974). Cross-validatory choice and assessment of statistical predictions. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 36(2), 111-133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1974.tb00994.x

Suh, C., & Punnett, L. (2022). High emotional demands at work and poor mental health in client-facing workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), Article 7530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127530

Trépanier, S. G., Forest, J., Fernet, C., & Austin, S. (2015). On the psychological and motivational processes linking job characteristics to employee functioning: Insights from self-determination theory. Work & Stress, 29(3), 286-305. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2015.1074957

Verzeletti, C., Zammuner, V. L., Galli, C., & Agnoli, S. (2016). Emotion regulation strategies and psychosocial well-being in adolescence. Cogent Psychology, 3(1), Article 1199294. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2016.1199294

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063-1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Appendix

Emotional Health Work Inventory (EHWI)

Instructions: Use the scale below and mark (X) the option that best reflects your emotion.

In the last few weeks, while working alone, I felt:

Note. * positive emotions = even numbers; negative emotions = odd numbers.