ISSN:1794-4724 | eISSN:2145-4515

Coparenting Intervention Programs: A Systematic Literature Review

Programas de intervención en coparentalidad: una revisión sistemática de la literatura

Programas de intervenção em coparentalidade: uma revisão sistemática da literatura

Thaís Ramos de Carvalho, Lívia Lira de Lima Guerra, Ligia de Santis, Elizabeth Joan Barham

Coparenting Intervention Programs: A Systematic Literature Review

Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, vol. 40, no. 2, 2022

Universidad del Rosario

Thaís Ramos de Carvalho a thais_rcarvalho@hotmail.com

Federal University of São Carlos, Brasil

Lívia Lira de Lima Guerra

Federal University of São Carlos, Brasil

Ligia de Santis

University San Francisco, Estados Unidos de América

Elizabeth Joan Barham

Federal University of São Carlos, Brasil

Received: february 07, 2022

Accepted: september 02, 2022

Additional information

To cite this article: Carvalho, T. R. Guerra, L. L. L., Santis, L., & Barham, E. J. (2022). Coparenting intervention programs: A systematic literature review. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, 40(2), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/apl/a.10330

Abstract: The coparenting relationship affects parents’ and children’s socioemotional well-being. Thus, we reviewed evidence in the scientific literature to describe the objectives and organization of coparenting intervention programs, to examine the design of these studies and summarize evidence concerning the effectiveness of these programs. The following electronic databases were used: Bireme, Psycnet, Periódicos capes, and IndexPsi Periódicos. The review was carried out in April 2020 with no restrictions involving the date of publication. The keywords used were “coparenting”, combined with any of the following terms “training”, “intervention”, or “program”, in Portuguese, English, and Spanish. Based on the study criteria 34 texts about 17 intervention programs were examined to gain information about research design, program objectives and format, topics covered, intervention strategies, and evidence of program effectiveness. We observed that an experimental design was used in two-thirds of the studies with pretest, posttest, and follow-up evaluations. In many programs, parenting was also addressed. An array of psychoeducational intervention strategies was used to improve abilities such as emotional regulation, bidirectional communication, and joint decisionmaking. The programs were effective in helping parents to develop a more positive coparenting relationship (for example, by increasing support and reducing conflicts) and to improve their parenting (by reducing harsh parenting behaviors), with longitudinal studies indicating the stability of these effects. These findings indicate that coparenting can be improved and that working on the coparenting relationship is an important way of strengthening the socioemotional well-being of parents and their children.

Keywords: Coparenting, intervention, evaluation, parenting, family adjustment.

Resumen: La relación de coparentalidad afecta el bienestar socioemocional de padres e hijos. Dada su importancia, revisamos la evidencia en la literatura científica para describir los objetivos y la organización de los programas de intervención en coparentalidad que han sido evaluados, examinar el diseño de los estudios de evaluación y resumir la evidencia relativa a la eficacia de estos. Se utilizaron las bases de datos electrónicas Bireme, Psycnet, Periódicos capes y IndexPsi Periódicos. La revisión se realizó en abril del 2020, sin restricciones en la fecha de publicación. La palabra clave utilizada fue coparenting, combinada con cualquiera de los siguientes términos: training, intervention, o program. En portugués, inglés y español. Se identificaron 34 textos de 17 programas de intervención. Estos artículos fueron examinados para obtener información sobre el diseño de la investigación, los objetivos y el formato del programa, los temas tratados, las estrategias de intervención y la evidencia de la eficacia del programa. Observamos que en dos tercios de los estudios se utilizó un diseño experimental con evaluaciones previas, posteriores y de seguimiento. En muchos programas también se abordó la crianza de los hijos. Se utilizó una serie de estrategias de intervención psicoeducativas para mejorar habilidades como la regulación emocional, la comunicación bidireccional y la toma de decisiones conjunta. Los programas fueron eficaces para ayudar a los padres a desarrollar una relación de coparentalidad más positiva (por ejemplo, aumentando el apoyo y reduciendo los conflictos) y mejorar su crianza (por ejemplo, reduciendo las conductas de crianza duras), con estudios longitudinales que indican la estabilidad de dichos efectos. Estos resultados muestran que la coparentalidad puede mejorarse y que trabajar en esa relación es una forma de fortalecer el bienestar socioemocional de padres e hijos.

Palabras clave: coparentalidad, intervención, evaluación, crianza, ajuste familiar.

Resumo: A relação coparental afeta o bem-estar socioemocional de pais e filhos. Dada a sua importância, revisamos as evidências na literatura científica para descrever os objetivos e a organização dos programas de intervenção coparental que foram avaliados, examinamos o desenho dos estudos de avaliação e resumimos as evidências sobre sua eficácia. Foram utilizadas as bases de dados eletrônicas Bireme, Psycnet, Periódicos capes e Periódicos IndexPsi. A revisão foi realizada em abril de 2020, sem restrições quanto à data de publicação. As palavras-chave utilizadas foram “coparenting”, combinada com qualquer um dos seguintes termos: “training”, “intervention” ou “program” em português, inglês e espanhol. Foram identificados 34 textos sobre 17 programas de intervenção. Esses artigos foram revisados para obter informações sobre o desenho da pesquisa, objetivos e formato do programa, tópicos abordados, estratégias de intervenção e evidências da eficácia do programa. Descobrimos que dois terços dos estudos usaram um desenho experimental com avaliações prévias, posteriores e de acompanhamento. A parentalidade também foi abordada em muitos programas. Uma série de estratégias de intervenção psicoeducativas foram utilizadas para melhorar habilidades como a regulação emocional, comunicação bidirecional e tomada de decisão conjunta. Os programas foram eficazes em ajudar os pais a desenvolver uma relação de coparentalidade mais positiva (por exemplo, aumentando o apoio e reduzindo conflitos) e melhorar sua parentalidade (por exemplo, reduzindo comportamentos parentais severos), com estudos longitudinais indicando a estabilidade desses efeitos. Esses resultados indicam que a coparentalidade pode ser aprimorada e que trabalhar a relação coparental é uma forma de fortalecer o bem-estar socioemocional de pais e filhos.

Palavras-chave: coparentalidade, intervenção, avaliação, parentalidade, ajustamento familiar.

The quality of family interactions has a strong influence on positive human development (Cowan & Cowan, 2002; Minuchin, 1982; Minuchin et al., 1999). Researchers have also observed that the coparenting relationship seems to be a factor that influences other family relationships, affecting the socioemotional wellbeing of each family member (Feinberg, 2003; Margolin et al., 2001; McHale, 1995). A coparenting partner is a person who shares the long-term responsibility for caring for a child with another. Working closely with another person on such a complex and significant task as this and over such a long period of time, however, can be difficult (Guerra et al., 2020). This leads to the question: can we help parents (or other primary caregivers) establish more positive coparenting relationships? In this study, we reviewed findings on the design and effects of programs that aimed to help parents (or other parental figures) work together to manage the tasks involved in raising their children.

Identifying coparenting programs is not a straightforward task, as programs that address coparenting have often been added to parenting programs (Shapiro et al., 2011). Thus, it is important to define coparenting. Three of the most widely cited theoretical models of coparenting were developed by Margolin et al. (2001), Feinberg (2003), and Van Egeren and Hawkins (2004). The authors of these models understand coparenting as the interactions between two individuals (the biological parents or other primary caregivers) who take joint responsibility for the welfare of a particular child. Although there are some distinctions, the authors of all three models indicate that coparenting partners need to be able to deal with differences in their opinions about parenting, to express their approval and support for the other parent, to assume responsibilities for family-related tasks, and to avoid involving the child in interparental conflicts by using the child to help manage conflicts or by forming an alliance to exclude or disqualify the other parent.

In addition to describing and delimiting the concept of coparenting, many researchers have investigated how coparenting relates to family adjustment. For example, coparenting has a strong influence on parent-child relationships and parenting practices. Margolin et al. (2001) indicated that the extent to which parents collaborate with each other (positive coparenting) influences how they interact with their children and deal with stress related to their parenting roles. Böing and Crepaldi (2016) reported similar findings, indicating that approval of the partner’s parenting was an important predictor of parenting styles. The more strongly the mothers endorsed their husband’s parenting behaviors, the more likely they were to report that their husbands used a reciprocal, democratic parenting style. In addition, the greater the occurrence of undermining behaviors in the coparenting relationship, as reported by fathers, the higher the probability both parents would use an overly permissive style of parenting (Böing & Crepaldi, 2016).

Going one step further to look at how the coparenting relationship affects children’s developmental outcomes, Teubert and Pinquart (2010) conducted a meta-analysis, examining 59 studies in which statistical information was reported on the relationship between coparenting and indicators of child adjustment. Positive coparenting (high levels of cooperation and agreement and low levels of conflict and triangulation) had a strong positive association with desirable child development outcomes (social adjustment and emotional attachment), and a strong negative association with undesirable outcomes (internalizing and externalizing behavior problems). A more robust analysis of the effects of coparenting was made by examining only the results of longitudinal studies (nine studies with an average duration of 37 months). The authors concluded that the way parents interact with each other to raise their children is significantly related to the children’s psychological adjustment.

However, according to Sifuentes and Bosa (2010), although evidence for the importance of coparenting has been widely reported, most research has been conducted with parents whose children have a normal trajectory of development progress. Thus, the authors questioned whether parents of children with special needs, such as autism, require more elaborate adaptations in the family context and in the coparenting relationship between the parents. Compared to children who do not have special needs, raising a child with special needs requires more intensive parenting involvement and a greater need for additional help, but to the extent that the parents can support each other in establishing helpful ways to respond to their child’s needs, the quality of the coparenting relationship would still be expected to influence parent and child outcomes.

Considering this and other evidence that points to the influence of a positive coparenting relationship on the psychological adjustment of the parents and on important development outcomes for the children (Feinberg et al., 2009), researchers and practitioners began to invest in finding ways to improve this relationship. In their study, Feinberg et al. (2009) presented strong evidence that addressing coparenting and other family relationships in intervention programs can benefit family dynamics and child development.

In the years that followed, additional efforts were made to improve coparenting relationships through the development of interventions focused directly on the coparenting relationship and including elements related to coparenting in parenting programs. Evidence on the effectiveness of intervention programs that included coparenting as one of its components points to improvements for various family members and for key relationships in the family system, including the promotion of marital satisfaction, better parenting practices, self-regulation in infants, social competence in children, and parental self-efficacy (Feinberg & Kan, 2008; Feinberg et al., 2009; 2015). However, we were unable to find a review study that could provide researchers and practitioners with an overview of the intervention programs that have been evaluated, the quality of the studies conducted to evaluate these programs, differences in the target population for each program, and the outcomes that have been reported. Thus, the goal of this paper was to review the scientific literature to describe the objectives and organization of the coparenting intervention programs, examine the design of the evaluation studies, and summarize evidence concerning the effectiveness of these programs.

Method

Data collection procedures

In accordance with the prisma statement (Liberati et al., 2009), a systematic review was carried out in April 2020 using the following databases: Bireme, Psycnet, Periódicos capes, and IndexPsi Periódicos. No restrictions were used concerning the date of publication. Considering the objectives of this study, the following keyword combinations were used: “coparenting” and “training,” “intervention,” “program” in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. All the keywords were inserted in the “subject” field. No restrictions were imposed regarding the date of publication, the use of a comparison or control group, a particular outcome variable, or any other aspects of study design (Liberati et al., 2009). Based on the prisma statement, additional searches may be conducted when the researchers need more information about any of the studies in terms of procedures, outcomes, or about the intervention programs themselves.

Exclusion criterio

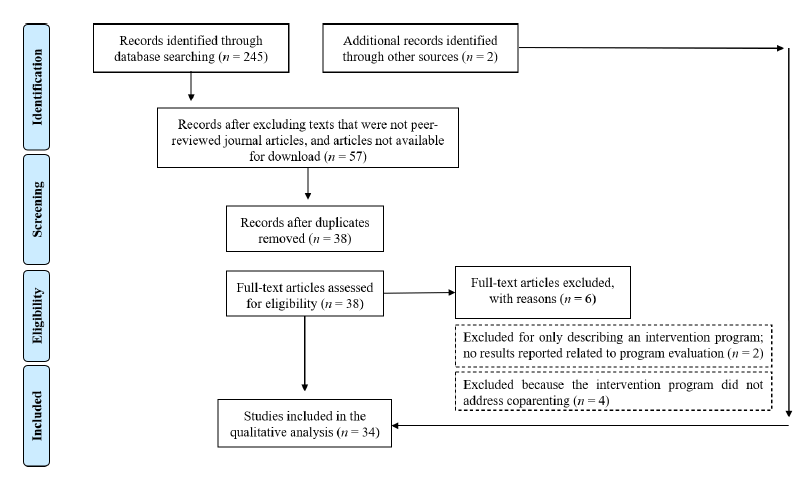

During the first phase of the review, the titles and abstracts of each article were independently analyzed by two researchers to decide on the exclusion of studies. Disagreements were resolved by reaching consensus in discussions that included a third researcher. Only scientific articles which had undergone peer review and had the full version available for download were considered. Of the 245 publications initially identified, 57 met these criteria. Texts retrieved multiple times in different databases were considered only once, reducing the total number of papers to 38.

After considering these initial criteria, a group of three researchers applied further exclusion criteria; they read the 38 studies (once again, disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached). These additional criteria were: (a) the study was not about an intervention program, (b) the coparenting relationship was not addressed in the intervention program, and (c) no program evaluation results were presented. Based on these criteria, another six articles were excluded, resulting in the retention of 32 studies for qualitative analysis. There was 94.7% agreement among the evaluators about the inclusion or exclusion of each study. At this point, two additional texts were included (Gaskin-Butler et al., 2015; Ward et al., 2017) to obtain information about topics covered and intervention strategies used in two of the programs, as this information was not described in the initial set of articles. In Figure 1, we present a summary of the criteria used to exclude articles and the number of articles excluded based on each criterion.

Data analysis procedures

To increase the quality of the data analysis process, three researchers analyzed the content of the 34 selected articles, obtaining information that describes 17 intervention programs. To guide the analysis of the programs found in the different studies, the following information was registered: program objectives, research design used to evaluate each program, program format (number of sessions, individual or group setting, and target participant characteristics), topics covered, intervention strategies used, evidence of program effectiveness, and study limitations.

Results

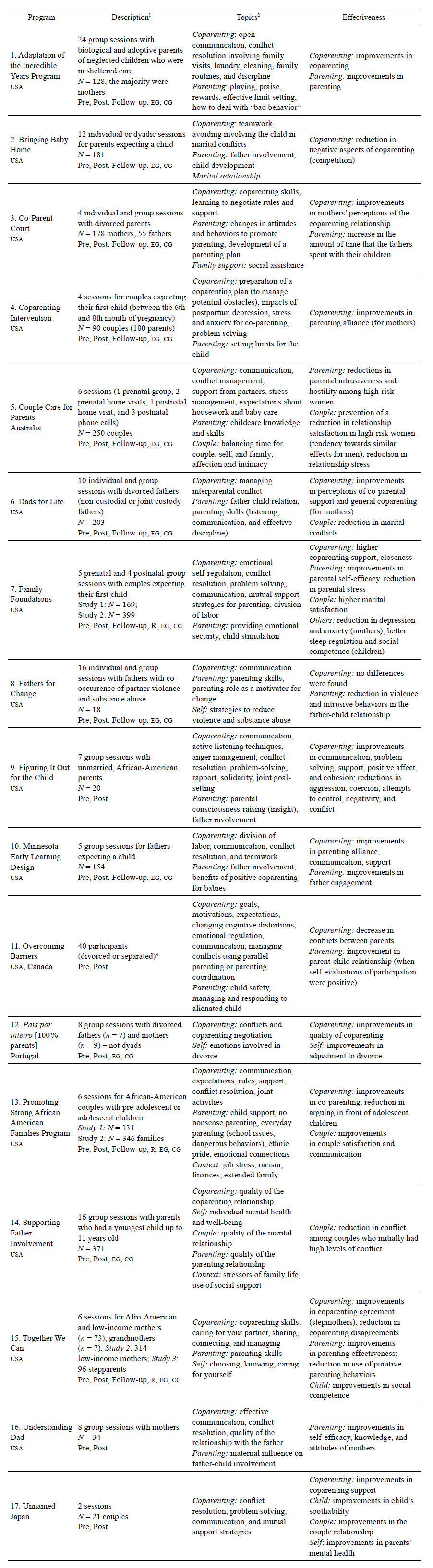

Sufficient information was found to examine 17 intervention programs, presented in alphabetical order: Adaptation of the Incredible Years (Linares et al., 2006), Bringing Baby Home (bbh) (Shapiro et al., 2011), Co-Parent Court (cpc) (Marczak et al., 2015), Coparenting Intervention (Doss et al., 2014), Couple Care for Parents (Petch et al., 2012), Dads for Life (dfl) (Cookston et al., 2007), Family Foundations (ff) (Brown, Feinberg & Kan, 2012; Brown, Goslin & Feinberg, 2012; Feinberg et al., 2009; Feinberg et al., 2010; Feinberg et al., 2014; Feinberg et al., 2015; Feinberg, Jones, Hostetler et al., 2016; Feinberg, Jones, Roettger et al., 2016; Feinberg & Kan, 2008; Jones et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2018; Kan & Feinberg, 2015; Solmeyer et al., 2013), Fathers for Change (Stover, 2015), Figuring It Out for the Child (fioc) (Gaskin-Butler et al., 2015; McHale et al., 2015), Minnesota Early Learning Design (meld) (Fagan, 2008), Overcoming Barriers Program (obp) (Saini, 2019; Ward et al., 2017), Pais por inteiro (papi) [100 % parents] (Lamela et al., 2010), Promoting Strong African American Families Program (Prosaaf) (Beach et al., 2014; Lavner et al., 2019), Supporting Father Involvement (sfi) (Epstein et al., 2015), Together We Can (twc) (Adler-Baeder et al., 2016; Garneau & Adler-Baeder, 2015; Kirkland et al., 2011), Understanding Dad (Fagan et al., 2015), and an Unnamed program, conducted by Takeishi et al. (2019).

Although all the programs were designed to improve the coparenting relationship, some of them had additional goals related to improving the marital relationship, parenting, and father involvement. In addition, the PApi and obp sought to help parents with the process of emotional adaptation to divorce, and the Fathers for Change program worked on issues related to the reduction of violence and substance abuse. In Table 1, we present a summary of the information we gathered, including the name of each program, the country where the programs were evaluated, information about the program-evaluation research design, program format, topics covered, and evidence of the effectiveness of each program.

Most of the programs were conducted in the usa, with only four programs conducted in other countries (Japan, Australia, Portugal, and Canada). The Japanese program was based on the Family Foundations program. Two thirds of the programs (64.7 %) were evaluated using an experimental study design (random assignment to intervention and control groups) with a pre-test, a post-test, and at least one follow-up evaluation. Replication studies were found for three programs: Family Foundations, Prosaaf, and Together We Can.

There were variations in the structure of the intervention programs, considering the number of sessions (ranging from 2 to 24), format (group, individual, or mixed), and the topics covered. Nearly all the programs used a group intervention format, often mixed with individual sessions; 12 of the programs were comparatively brief (up to 8 sessions). The obp was conducted in a “camp” (or retreat) context. Most of the programs were offered during the transition to parenthood period, but four programs were designed for divorced parents, and one was for parents with adolescent children.

The programs covered coparenting issues but also offered guidance on topics such as parenting, the couple’s relationship, and participant’s wellbeing. In addition, most programs used a variety of intervention strategies, such as modeling (using videos or film clips), instructing (using program pamphlets or participant manuals, readings, and discussions), behavioral training (via role-play activities, games, working on communication strategies, teaching problem-solving techniques, improving stress and anger management abilities), emotional involvement (using self-revelation), and tasks for establishing behavior changes in the parents’ home environment (using homework and a coparenting plan).

The effects of the intervention programs were mostly evaluated using self-report instruments, although some researchers used observational measures or interviews. In one study, the effects of the Family Foundations program were also tested using a biological measure (the parents’ cortisol levels). In three studies, however, although improving the coparenting relationship was a program goal, this relationship was not evaluated. Improvements in the coparenting relationship were observed for 13 of the 17 programs, with some researchers reporting general improvements while others indicated changes in more specific areas of coparenting, such as increased coparenting support, closeness, communication, and agreement, as well as reductions in coparenting disagreements and conflicts.

Given that the quality of the coparenting relationship is intertwined with parenting behaviors and the quality of the marital relationship, we also examined results related to these outcomes. Although not all the programs focused on parenting or the couple’s relationship, improvements in parenting were reported for 9 of the 12 programs that addressed parenting, including results such as a greater sense of parenting self-efficacy, lower parental intrusiveness and hostility, higher father engagement, and improvements in parent-child relationships. Significant improvements in the couple’s relationship satisfaction were also reported for four of the programs.

Additional indirect effects of improvements in coparenting were also measured. Improvements in the parents’ emotional well-being (lower depression and anxiety, better adjustment to divorce) were evaluated and confirmed for four programs. Furthermore, the Family Foundations program was successful in establishing positive coparenting relationships, as expected, which appears to have buffered the negative impacts of parenting stress on the mothers’ mental health (depression and anxiety symptoms), the babies’ birthweight, and the number of days of hospitalization at birth. During follow-up studies, further benefits for the children were observed, including greater soothability, better sleep regulation, and higher social competence.

A buffering effect of coparenting was also reported for the Coparenting Intervention program, which was also effective in helping the parents establish a good coparenting relationship. When this relationship was better, it contributed to preventing unhealthy levels of perceived stress.

Although many of the studies were of high scientific caliber, the authors of the studies we reviewed noted various research limitations. Some noted problems such as small sample sizes, non-representative samples regarding the phenomenon of interest (truncated variance problems), non-generalizable effects due to targeting particular groups of parents (e. g., divorced, high-risk, or low-income parents/ fathers), use of only one measurement method (e. g., only self-report instruments or only observational measures), use of instruments lacking studies to examine evidence of validity, difficulties evaluating the effects of any specific component of the program due to the use of a complex intervention strategy (for example, activities on coparenting and parenting), small effect sizes, not enough sessions focused on developing coparenting skills, no evaluation of the effects of the program on the child, absence of a control group, no follow-up evaluation, and no replication studies to confirm the results.

Discussion

An important issue in intervention work on family functioning is to decide who to work with (the target population) and at what point in their lives. Many of the coparenting programs were offered during the transition to parenthood period, as this is a phase when parents may be more open to outside assistance and a time when they are actively investing in constructing a positive coparenting relationship (Feinberg, 2002; Feinberg et al., 2009). Another finding that justifies working with parents during the transition to parenthood period is that rates of depression, anxiety, and marital conflict usually increase substantially during this period, with negative effects on child development (Feinberg et al., 2009).

Another factor that varied across studies and programs was the target population—some researchers worked with couples, while others worked only with mothers or only with fathers. The Fathers for Change, meld, and dfl1 intervention programs were offered only to fathers; the Understanding Dad program was offered only to mothers. The fact that a given program was offered to only one member of the parenting dyad does not mean that the program cannot be used with the other parent (or with both parents together). However, these programs would need to be evaluated to establish their effectiveness with an expanded population. Among the interventions that were offered to both parents, one presented evidence of efficacy only for the mothers (the Coparenting Intervention program), which also points to the need to understand differences in program efficacy related to the participant’s gender.

Although prevention work during the transition to parenthood is of unquestionable importance, interventions that are appropriate for other stages of family life are also needed. The coparenting relationship changes over time, as the children move from one developmental stage to the next and as the parents’ circumstances change. The results of the intervention studies that were carried out with parents of older children (Frascarolo et al., 2018) and divorced parents (for example, Lamela et al., 2010) signal that, even when the children are older and interparental conflict is higher, many parents can improve their coparenting relationship.

According to Shapiro et al. (2011), most early coparenting programs were designed to promote a more collaborative relationship among divorced parents. Later, researchers began to test coparenting as a means of encouraging father involvement, while others focused on promoting good quality coparenting relationships as the main objective of their intervention program. Despite this diversity, the structure of the programs was generally similar to those of earlier studies in the area of family intervention research (Cowan & Cowan, 1995, 2002; Hawkins et al., 2008; Micham-Smith & Henry, 2007).

In all the programs, at least one of the objectives was to promote a more positive coparenting relationship. However, most of the programs had additional objectives, such as improving parenting behaviors or the marital relationship. Complex problems, such as family adjustment, require multi-component intervention programs (Moore et al., 2015). The combination of objectives reflected the researchers’ expectations that better quality coparenting relationships, based on bidirectional communication and collaboration, can fortify their efforts to improve parent-child interactions, as well as to develop the non-parenting components of the couple’s relationship, as the associations between coparenting and other family relationships have already been documented in the scientific literature (Barzel & Reid, 2011; Feinberg et al., 2007; Feinberg et al., 2012; Morrill et al., 2010; Norlin & Broberg, 2013; Pedro & Ribeiro, 2015; Venâncio, 2015).

In general, professional help aided the parents to improve interpersonal skills that are important for coparenting, such as communication, problem solving, improving stress, anger management abilities, and being supportive. Most of the programs were prepared by program developers who organized activities based on a behavioral change model that addresses links between thoughts, feelings, and interpersonal behaviors (as described by Moore et al., 2015). Thus, parents built up skills in a cumulative and integrative way, with each skill increasing their ability to manage stressful coparenting situations.

The intervention strategies used in the programs reviewed involved active learning techniques often used in cognitive-behavioral therapy (Guerra et al., 2020). These strategies included social learning strategies (such as modeling, instructing, behavioral feedback, and social reinforcement), emotional engagement strategies (such as self-revelation), the development of self-monitoring and self-regulation abilities (with respect to thoughts, feelings, and verbal behavior), and tasks to promote transferring new skills to the home environment. These are impactful strategies that can help people expand their interpersonal skills, leading to long-term benefits.

Although there were many differences among the programs, improvements in the coparenting relationship were reported in most of the studies. This provides evidence that the quality of the coparenting relationship can be improved using professional intervention techniques, such as the strategies described in the programs we examined. A higher quality coparenting relationship helps parents work together to negotiate the difficulties of raising a child (Feinberg, 2003).

It also appears that improvements in coparenting were typically accompanied by improvements in parenting and satisfaction with the marital relationship, confirming that coparenting, parenting, and the quality of the marital relationship, seem to go hand in hand (Feinberg et al., 2009). Furthermore, for some programs, additional impacts were evaluated, considering a variety of problems that typically occur during the period of transition to parenthood. In the Family Foundations program, for example, stronger coparenting relationships attenuated mothers’ mental health problems and were also associated with a lower incidence of problems related to the baby’s birth weight and of other complications that lead to extended hospital stays. It is important to highlight, however, that the number of replication studies and longitudinal program-evaluation studies is still small.

Finally, it is important to consider the limitations of this review study linked to methodological issues. The choice of keywords, databases, and languages contribute to finding studies on the topic of interest, but there may be other studies that were not included in the present review that describe additional results or other intervention programs focused on coparenting. Thus, review studies that use other keywords and that cover research published in other languages are needed to add to the results found.

Final considerations

In this paper, we described intervention programs that had, as one of their objectives, the promotion of a positive coparenting relationship and examined evidence of the effectiveness of each program. It is important for researchers and professionals to have access to a summary of findings on the effects of intervention programs that address coparenting, so they can examine evidence about how to foster this relationship and about some of the benefits of helping parents to interact positively with each other to raise their child.

The outcomes reported characterize an advance in coparenting research, as the results of intervention studies, compared to correlational studies, offer more robust scientific evidence. We already knew that coparenting was associated with family functioning (McHale & Rasmussen, 1998). Now we know that it is possible to improve the coparenting relationship and that these improvements can help parents to interact more constructively with their children and with each other, not only in the coparenting relationship but also in their marital relationship, contributing to the parents’ and their children’s socioemotional wellbeing.

The programs reviewed dealt with multiple aspects of family life. Although the focus on coparenting represents a relatively new contribution, it is important to realize that working only on coparenting is probably not sufficient to reach the reported outcomes for the children’s development and for parents’ mental health. To make further progress in coparenting, we offer three suggestions. First, coparenting programs should be evaluated in a wider range of cultural contexts. Findings from a greater number of countries will help to identify ways to improve them. In the present review, although we searched for studies using North and South American databases and were able to analyze texts written in English, Portuguese, or Spanish, only four of the studies we reviewed were conducted outside the USA.

Additionally, given the rapid evolution of technologies and the increasing use of these tools, it will be important to develop interventions that can be applied in multiple formats (such as face-toface and online versions). This could favor the dissemination of these programs, permitting not only an increase in the number of people assisted but also leading to the possibility of reaching a greater range of people. Some parents are more likely to benefit from in-person programs at local community centers, while others, for logistical reasons, can more easily participate if they do not have to travel or leave work early.

Finally, given that research on coparenting programs is still at an intermediate stage of evidence-gathering, researchers should invest in conducting longitudinal studies. For example, can programs such as the ones reviewed permanently interrupt the transmission of interpersonal behaviors that lead to intimate partner violence, parental depression, divorce, and harsh parenting? How does a more cooperative coparenting relationship affect the children as teenagers, the emotional well-being of young adults who have left their parents’ home, and coparenting behaviors when the grown-up children become parents? The answers to these questions may contribute to reducing long-standing social problems and to promoting more positive socioemotional interactions in family contexts and beyond.

References

Adler-Baeder, F., Garneau, C., Vaughn, B., Mcgill, J., Harcourt, K. T., Ketring, S., & Smith, T. (2016). The effects of mother participation in relationship education on coparenting, parenting, and child social competence: Modeling spillover effects for low-income minority preschool children. Family Process, 57(1), 1–18. http://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12267

Barzel, M., & Reid, G. J. (2011). A preliminary examination of the psychometric properties of the Coparenting Questionnaire and the Diabetes-Specific Coparenting Questionnaire in families of children with Type I diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 36(5), 606–617. http://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsq103

Beach, S. R. H., Barton, A.W., Lei, M. K., Brody, G. H., Kogan, S. M., Hurt, T. R., Fincham, F. D., & Stanley, S. M. (2014). The effect of communication change on long-term reductions in child exposure to conflict: Impact of the Promoting Strong African American Families (Prosaaf) program. Family Process, 53(4), 580–595. http://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12085

Böing, E., & Crepaldi, M. A. (2016). Relação pais e filhos: compreendendo o interjogo das relações parentais e coparentais. Educar em Revista, 59, 17–33. http://doi.org/10.1590/0104-4060.44615

Brown, L. D., Feinberg, M. E., & Kan, M. L. (2012). Predicting engagement in a transition to parenthood program for couples. Evaluation and Program Planning, 35, 1–8. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.05.001

Brown, L. D., Goslin, M. C., & Feinberg, M. E. (2012). Relating engagement to outcomes in prevention: The case of a parenting program for couples. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50, 17–25. http://doi.org/10.1007s10464-011-9467-5

Cookston, J. T., Braver, S. L., Griffin, W. A., De Lusé, S. R., & Miles, J. C. (2007). Effects of the dads for life intervention on interparental conflict and coparenting in the first two years after divorce. Family Process, 46(1), 123–137. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00196.x

Cowan, C. P., & Cowan, P. A. (1995). Interventions to ease the transition to parenthood: Why they are needed and what they can do. Family Relations: Journal of Applied Family & Child Studies, 44(4), 412–423. http://doi.org/10.2307/584997

Cowan, P. A., & Cowan, C. P. (2002). Interventions as tests of family systems theories: Marital and family relationships in children’s development. Development and Psychopathology, 14(4), 731–759. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579402004054

Doss, B. D., Cicila, L. N., Hsueh, A. C., Morrison, K. R., & Carhart, K. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of brief coparenting and relationship interventions during the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(4), 483–494. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0037311

Epstein, K., Pruett, M. K., Cowan, P., Cowan, C., Pradhan, L., Mah, E., & Pruett, K. (2015). More than one way to get there: Pathways of change in coparenting conflict after a preventive intervention. Family Process, 54(4), 610–618. http://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12138

Fagan, J. (2008). Randomized study of a pre-birth coparenting intervention with adolescent and young fathers. Family Relations, 57(3), 309–323. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00502.x

Fagan, J., Cherson, M., Brown, C., & Vecere, E. (2015). Pilot study of a program to increase mothers’ understanding of dads. Family Process, 54(4), 581–589. http://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12137

Feinberg, M. E. (2002). Coparenting and the transition to parenthood: A framework for prevention. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 5, 173–195. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019695015110

Feinberg, M. E. (2003). The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parent: Science and Practice, 3(2), 95–131. http://doi.org/10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01

Feinberg, M. E., Brown, L. D., & Kan, M. L. (2012). A multi-domain self-report measure of coparenting. Parenting, Science and Practice, 12(1), 1–21. http://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2012.638870

Feinberg, M. E., Jones, D. E., Hostetler, M. L., Roettger, M. E., Paul, I. M., & Ehrenthal, D. B. (2016). Couple-focused prevention at the transition to parenthood, a randomized trial: Effects on coparenting, parenting, family violence, and parent and child adjustment. Society for Prevention Research, 17, 751–764. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0674-z

Feinberg, M. E., Jones, D. E., Kan, M. L., & Goslin, M. C. (2010). Effects of family foundations on parents and children: 3.5 years after baseline. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(5), 532–542. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0020837

Feinberg, M. E., Jones, D. E., Roettger, M. E., Hostetler, M. L., Sakuma, K., Paul, I. M., & Ehrenthal, D. B. (2016). Preventive effects on birth outcomes: Buffering impact on maternal stress, depression, and anxiety. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20, 56–65. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-015-1801-3

Feinberg, M. E., Jones, D. E., Roettger, M. E., Solmeyer, A. R., & Hostetler, M. L. (2014). Longterm follow-up of a randomized trial of family foundations: Effects on children’s emotional, behavioral, and school adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 28(6), 821–831. http://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000037

Feinberg, M. E., & Kan, M. L. (2008). Establishing family foundations: Intervention effects on coparenting, parent/infant well-being, and parent-child relations. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(2), 253–263. http://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.253

Feinberg M. E., Kan M. L., & Goslin M. C. (2009). Enhancing coparenting, parenting, and child self-regulation: Effects of family foundations 1 year after birth. Prevention Science, 10, 276– 285. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-009-0130-4

Feinberg, M. E., Kan, M. L., & Hetherington, E. M. (2007). The longitudinal influence of coparenting conflict on parental negativity and adolescent maladjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(3), 687–702. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00400.x

Feinberg, M. E., Roettger, M. E., Jones, D. E., Paul, I. M., & Kan, M. L. (2015). Effects of a psychosocial couple-based prevention program on adverse birth outcomes. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19, 102–111. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1500-5

Frascarolo, F., Fivaz-Depeursinge, E., & Philipp, D. (2018). The child and the couple: From zero to fifteen. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27, 3073–3084. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1090-8

Garneau, C. L., & Adler-Baeder, F. (2015). Changes in stepparents’ coparenting and parenting following participation in a community-based relationship education program. Family Process, 54(4), 590–599. http://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12133

Gaskin-Butler, V. T., McKay, K., Gallardo, G., Salman-Engin, S., Little, T., & McHale, J. P. (2015). Thinking 3 rather than 2 + 1: How a coparenting framework can transform infant mental health efforts with unmarried African American parents. From Zero to Three, 35(5), 49–58. http://hdl.handle.net/11693/48858

Guerra, L. L. L., Carvalho, T. R. C., Santis, L., & Barham, E. J. (2020). Programas de intervenção em coparentalidade: tópicos abordados e técnicas cognitivo-comportamentais utilizadas. In B. Cardoso & K. Paim (Eds.), Terapias cognitivo-comportamentais para casais e famílias: bases teóricas, pesquisas e intervenções (pp. 397–420). Synopsis.

Hawkins, A. J., Lovejoy, K. R., Holmes, E. K., Blanchard, V. L., & Fawcett, E. (2008). Increasing fathers’ involvement in childcare with a couple-focused intervention during the transition to parenthood. Family Relations, 57(1), 49–59. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00482.x

Jones, D. E., Feinberg, M. E., & Hostetler, M. L. (2014). Costs to implement an effective transition-to-parenthood program for couples: Analysis of the Family Foundations program. Evaluation and Program Planning, 44, 59–67. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2014.02.001

Jones, D., Feinberg, M., Hostetler, M., Roettger, M., Paul, I. M., & Ehrenthal, D. B. (2018). Family and child outcomes 2 years after a transition to parenthood intervention. Family Relations, 67(2), 270–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12309

Kan, M. L., & Feinberg, M. E. (2015). Impacts of a coparenting-focused intervention on links between pre-birth intimate partner violence and observed parenting. Journal of Family Violence, 30, 363–372. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9678-x

Kirkland, C. L., Skuban, E. M., Adler-Baeder, F., Ketring, S. A., Bradford, A., Smith, T., & Lucier-Greer, M. (2011). Effects of relationship/ marriage education on co-parenting and children’s social skills: Examining rural minority parents’ experiences. Early Childhood Research and Practice, 13(2). https://ecrp.illinois.edu/v13n2/kirkland.html

Lamela, D., Castro, M., & Figueiredo, B. (2010). Pais por inteiro: Preliminary evaluation of the effectiveness of a group intervention for divorced parents. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 23(2), 334–344. http://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722010000200016

Lavner, J. A., Barton, A. W., & Beach, S. R. H. (2019). Improving couples’ relationship functioning leads to improved coparenting: A randomized controlled trial with rural African American couples. Behavior Therapy, 50(6), 1016–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2018.12.006

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The prisma statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), Article e1000100. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

Linares, L. O., Montalto, D. M., Li, M., & Oza, V. S. O. (2006). A promising parenting intervention in foster care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(1), 32–41. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.32

Marczak, M. S., Becher, E. H., Hardman, A. M., Galos, D. L., & Ruhland, E. R. (2015). Strengthening the role of unmarried fathers: Findings from the co-parent court project. Family Process, 54(4), 630–638. http://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12134

Margolin, G., Gordis, E. B., & John, R. S. (2001). Coparenting: A link between marital conflict and parenting in two-parent families. Journal of Family Psychology, 15(1), 3–21. http://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.15.1.3

McHale, J. P. (1995). Coparenting and triadic interactions during infancy: The roles of marital distress and child gender. Developmental Psychology, 31(6), 985–996. http://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.31.6.985

McHale, J. P., & Rasmussen, J. L. (1998). Coparental and family group-level dynamics during infancy: Early family precursors of child and family functioning during preschool. Development and Psychopathology, 10(1), 39–59. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579498001527

McHale, J. P., Salman-Engin, S., & Coovert, M. D. (2015). Improvements in unmarried African-American parents’ rapport, communication, and problem-solving following a prenatal coparenting intervention. Family Process, 54(4), 619–629. http://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12147

Mitcham-Smith, M., & Henry, W. J. (2007). High conflict divorce solutions: Parents’ coordination as an innovative coparenting intervention. The Family Journal, 15(4), 368–373. http://doi.org/10.1177/1066480707303751

Minuchin, S. (1982). Families: Functioning and Treatment (Jurema Alcides Cunha, Trad.). Artes Médicas.

Minuchin, P., Colapinto, J., & Minuchin, S. (1999). Working with poor families. Artes Médicas.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The prisma Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The prisma statement. PLoS Med, 6(7), Article e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Moore, G. F., Audrey, S., Barker, M., Bond, L., Bonell, C., Hardeman, W., Moore, L., O’Cathain, A., Tinati, T., Wight, D., & Baird, J. (2015). Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. British Medical Journal, 350, Article h1258. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1258

Morril, M. I., Hines, D. A., Mahmood, S., & Córdova, J. V. (2010). Pathways between marriage and parenting for wives and husbands: The role of coparenting. Family Processes, 49(1), 59–73. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2010.01308.x

Norlin, D., & Broberg, M. (2013). Parents of children with and without intellectual disability: Couple relationship and individual well-being. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 57(6), 552–566. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2012.01564.x

Pedro, M. F., & Ribeiro, M. T. (2015). Portuguese adaptation of the coparenting questionnaire: Confirmatory factor analysis and validity and reliability studies. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 28(1), 116–125. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-7153.201528113

Petch, J. F., Halford, W. K., Creedy, D. K., & Gamble, J. (2012). A randomized controlled trial of a couple relationship and coparenting program (Couple care for Parents) for high- and lowrisk new parents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(4), 662–673. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0028781

Saini, M. (2019). Strengthening coparenting relationships to improve strained parent–child relationships: A follow-up study of parents’ experiences of attending the Overcoming Barriers Program. Family Court Review, 57(2), 217–230. http://doi.org/10.1111/fcre.12405

Shapiro, A. F., Nahm, E. Y., Gottman, J. M., & Content, K. (2011). Bringing baby home together: Examining the impact of a couple-focused intervention on the dynamics within family play. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(3), 337–350. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01102.x

Sifuentes, M., & Bosa, C. A. (2010). Criando pré-escolares com autismo: Características e desafios da coparentalidade. Psicologia em Estudo, 15(3), 477–485. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=287122134005

Solmeyer, A. R., Feinberg, M. E., Coffman, D. L., & Jones, D. E. (2013). The effects of the Family Foundations Prevention Program on coparenting and child adjustment: A mediation analysis. Society for Prevention Research, 15, 213–223. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-013-0366-x

Stover, C. S. (2015). Fathers for change for substance use and intimate partner violence: Initial community pilot. Family Process, 54(4), 600–609. http://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12136

Takeishi, Y., Nakamura, Y., Kawajiri, M., Atogami, F., & Yoshizawa, T. (2019). Developing a prenatal couple education program focusing on coparenting for Japanese couples: A quasiexperimental study. The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine, 249(1), 9–17. http://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.249.9

Teubert, D., & Pinquart, M. (2010). The association between coparenting and child adjustment: A meta-analysis. Parenting: Science and Practice, 10(4), 286–307. http://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2010.492040

Van Egeren, L., & Hawkins, D. (2004). Coming to terms with coparenting: Implications of definition and measurement. Journal of Adult Development, 11, 165–178. http://doi.org/10.1023/B:JADE.0000035625.74672.0b

Venâncio, A. B. (2015). Envolvimento paterno, coparentalidade e equilíbrio trabalho-família: um estudo correlacional (Master’s dissertation, Lisbon University). http://repositorio.ul.pt/bitstream/10451/23012/1/ulfpie047627_tm.pdf

Ward, P., Deutsch, R. M., & Sullivan, M. J. (2017). Overview of the Overcoming Barriers Approach. In A. M. Judge & R. M. Deutsch (Eds.), Overcoming parent-child contact problems: Familybased interventions for resistance, rejection, and alienation (pp. 131–151). Oxford University Press.

Notes

1

Although the mothers were not invited to participate in these programs, they completed the study measures.

Author notes

a Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Thaís Ramos de Carvalho, Federal University of São Carlos, Department of Psychology, Km 235 Washington Luís highway - SP-310, São Carlos, SP, Brazil 13565-905. Email: thais_rcarvalho@hotmail.com