Polyculturalism: Viewing Cultures as Dynamically Connected and its Implications for Intercultural Attitudes in Colombia

Policulturalismo: percibiendo las conexiones dinámicas entre culturas y sus implicaciones sobre las actitudes actitudes interculturales en Colombia

Policulturalismo: percebendo as conexões dinâmicas entre culturas e suas implicações sobre as atitudes interculturais na Colômbia

Polyculturalism: Viewing Cultures as Dynamically Connected and its Implications for Intercultural Attitudes in Colombia

Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, vol. 37, no. 1, 2019

Universidad del Rosario

Received: 23 August 2018

Accepted: 12 September 2018

Additional information

To quote this article: Rosenthal, L., Ramirez L, Levy, S., & Bernardo, A. (2019). Polyculturalism: viewing cultures as dynamicallyconnected and its implications for intercultural attitudes in Colombia. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, 37(1),133-151. Doi: https://doi.org/10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/apl/a.7175

Abstract: In our increasingly globalized world, we are more exposed to diverse people and cultures than ever before, making lay belief systems about cross-cultural influences as well as consequences of those beliefs for intercultural attitudes important to study. Over the past decade, there has been increasing immigration to Colombia, making it a particularly important place in which to understand people’s attitudes and intentions toward individuals from other countries. We previously found in the Philippines and the us that endorsement of polyculturalism —the belief that different racial and ethnic groups influence and are connected to each other— is associated to a range of positive intergroup attitudes. In the current research, we have built on these past findings to contribute to our understanding of intercultural dynamics in Latin America, exploring polyculturalism in a cross-sectional survey study with 423 adults born and living in Colombia. We found that endorsement of polyculturalism was associated to more positive attitudes toward people from other countries and greater friendship intentions toward immigrants from other countries moving to Colombia, while controlling for social dominance orientation, national identification, and feelings toward the self. We also found that there were mean differences in people’s attitudes and friendship intentions toward people from different countries, based on type and level of cultural influence. But, type of country, social dominance orientation, and national identification did not moderate associations of polyculturalism with attitudes and friendship intentions, which suggests that these associations are consistent. Future directions and implications of polyculturalism for understanding intergroup relations around the world are discussed.

Keywords Colombia, diversity, globalization, immigrants, intercultural attitudes, intergroup relations, polyculturalism.

Resumen: En un mundo cada vez más globalizado, estamos cada vez más expuestos a personas y culturas diversas. De ahí la importancia de investigar los sistemas de creencias existentes sobre las influencias transculturales y sus consecuencias. El aumento reciente de la migración hace de Colombia un lugar particularmente interesante para el estudio de las actitudes e intenciones hacia individuos de otras culturas. Hallazgos previos en las Filipinas y Estados Unidos sugieren que la creencia en el policulturalismo —en que los diferentes grupos étnicos y raciales están conectados y se influencian mutuamente— está asociada con una variedad de actitudes positivas. Esta investigación construye sobre estos hallazgos y contribuye a la comprensión de las dinámicas con una variedad intercultural en América Latina, explorando sobre policulturalismo en un estudio transversal que incluyó 423 habitantes nativos colombianos. Encontramos que, controlando la orientación a la dominancia social, la identificación nacional, y la autoestima, la creencia en el policulturalismo está asociada a actitudes más positivas e intención de amistad hacia inmigrantes de otros países a Colombia. También encontramos diferencias significativas en las actitudes e intenciones de amistad hacia personas de diferentes países, dependiendo del tipo y nivel de influencia cultural. No encontramos evidencia de moderación de las asociaciones entre policulturalismo y actitudes e intenciones de amistad, por parte de las variables tipo de país, orientación a la dominancia social e identificación nacional, lo cual sugiere la consistencia de estas asociaciones. Finalmente discutimos las implicaciones de estos hallazgos sobre el papel del policulturalismo en la comprensión de las relaciones intergrupales en el mundo.

Palabras clave: Colombia, diversidad, globalización, inmigrantes, actitudes interculturales, relaciones intergrupales, policulturalismo.

Resumo: No mundo cada vez mais globalizado, estamos cada vez mais expostos a pessoas e culturas diversas. Daí a importância de investigar os sistemas de crenças existentes sobre as influências transculturais e suas consequências. O aumento recente da migração faz da Colômbia um lugar particularmente interessante para o estudo das atitudes e intenções para indivíduos de outras culturas. Resultados prévios nas Filipinas e os Estados Unidos sugerem que a crença no policulturalismo –em que os diferentes grupos étnicos e raciais estão conectados e se influenciam mutuamente– está associada com variedade de atitudes positivas. Esta pesquisa, constrói sobre estes resultados e contribui à compreensão das dinâmicas interculturais na América Latina, explorando sobre policulturalismo em um estudo transversal que incluiu 423 habitantes nativos colombianos. Encontramos que, controlando a orientação à dominância social, a identificação nacional, e a autoestima, a crença no policulturalismo está associada a atitudes mais positivas e intenção de Amizade a imigrantes de outros países à Colômbia. Também encontramos diferenças significativas nas atitudes e intenções de amizade a pessoas de diferentes países dependendo do tipo e nível de influência cultural. Não encontramos evidência de moderação das associações entre policulturalismo e atitudes e intenções de amizade, por parte das variáveis tipo de país, orientação à dominância social e identificação nacional o qual sugere a consistência destas associações. Finalmente discutimos as implicações destes resultados sobre o papel do policulturalismo na compreensão das relações intergrupais no mundo.

Palavras-chave: Colômbia, diversidade, globalização, imigrantes, atitudes interculturais, relações intergrupais, policulturalismo.

Introduction

With increasing globalization, individuals from all over the world are more exposed to diverse people and cultures than ever before, making the study of lay belief systems about cross-cultural contact and influences as well as the consequences of those beliefs for intercultural attitudes and behaviors important to study (e.g., Chiu, Gries, Torelli & Cheng, 2011; Moghaddam, 2012; Verkuyten, 2005; Zirkel, 2008). Lay belief systems about cross-cultural contact and influences have not received much attention in research in Latin America despite their relevance, as this is a region of the world with a richly diverse history, as well as with significant and changing migration patterns (Donato, Hiskey, Duran & Massey, 2010). Recently, because of globalization and the onset of the global economic recession in 2007, changes in migration patterns have been documented across Latin America; yet, there is lack of sufficient research to understand the context in which intercultural relations take place in this region of the world (Cabieses, Tunstall, Pickett & Gideon, 2013).

Colombia in particular is currently a place in which it is important to study attitudes and intentions toward individuals from other countries because over the last decade, increasing numbers of people have been immigrating to Colombia from other countries, and there have been changes in patterns of intercultural contact (Migración Colombia–oim, 2013; oim, 2012). Further, the history of and continued cultural influences on Colombia that vary from different countries may create unique feelings toward people from those different countries. For example, Colombians’ attitudes toward people from countries that have had strong influences through colonization and imperialism, such as Spain, the us, and England, may be different than attitudes toward people from countries that are neighboring and have many shared experiences, such as Ecuador and Venezuela (Telles & Bailey, 2013). We previously found in the Philippines and us that greater endorsement of polyculturalism — the belief that different racial and ethnic groups interact with, influence, and are connected to each other— is associated with more positive attitudes toward people from other countries, including those immigrating to one’s own country (Bernardo, Rosenthal, & Levy, 2013), suggesting studying polyculturalism might also contribute to our understanding of intercultural dynamics in Colombia. In the current investigation, we explored whether polyculturalism is associated with more positive intercultural attitudes and intentions among adults in Bogotá, the capital of Colombia, which is one of the major receptors of the country’s internal and external migration. We also explored whether those intercultural attitudes and intentions, as well as their associations with polyculturalism, vary from country to country, based on type and level of cultural influence.

Colombia

Colombia, similar to other countries in Latin America, is a country with a long history of cross-cultural contact and immigration, including that due to Spanish colonizers starting to come at the end of the 15th century to conquer and exploit the land and Indigenous peoples who lived there, and then later bringing enslaved peoples from Africa for labor (Migración Colombia–oim, 2013; Telles & Bailey, 2013). Since independence and the foundation of the Republic of Colombia in the early 1800s, policies were developed that encouraged immigration, mainly from Europe (Gómez, 2009; Hering Torres, 2012; oim, 2012), but fewer Europeans moved to Colombia than to other places in South America, such as Argentina (Tovar Pinzon, 2001). Starting at the end of the 19th and continuing through the 20th century, a significant number of people immigrated from European, Middle Eastern, and North American countries (d’Anglejan, 2009). Since the 1960’s, more people were emigrating from than immigrating to Colombia, mainly due to economic and security reasons ( oim, 2012). In 1990, Colombia implemented strategies to stimulate foreign economic investment, after which there was a small increase in the numbers of people immigrating to Colombia, mainly from Ecuador, the us, and Venezuela ( oim, 2012). Since 2007, there has been a significant increase in the number of working visas distributed by Colombia mainly for people arriving from Spain, the us, Venezuela, and other South American countries ( oim, 2012).

In addition to immigration, there has been cultural influence from other countries in Colombia throughout history. Historically through colonization and imperialism, European countries —especially Spain, but also, to a lesser degree, other countries such as the uk— have exerted a powerful influence on Colombia as well as other Latin American countries (Telles & Bailey, 2013). In the past several decades, the us has also exerted considerable influence on Colombia due to the us’ position as a dominant economic and political power in the region (Harris & Nef, 2008). Yet, the consequences of the dominant roles of countries like Spain and the us on Latin America, including culture and social relations, have not received enough attention. Even scarcer is research on consequences of the mutual impact between Latin American countries and cultures, such as between Colombia and neighboring countries like Ecuador and Venezuela, which have many similarities, such as their ethnic composition, and their common history of colonization by and subsequent independence from Spain, among other things. Given these dynamics, Colombia is an important place in which to study people’s current attitudes and intentions toward individuals from other countries, including examining how those attitudes and intentions may vary by country depending on the type (imperialist/dominating versus mutual/peer) and level (high versus low) of influence.

For example, some empirical evidence suggests that the experience of colonization may affect people´s self-image (Varas-Diaz & Serrano-Garcia, 2003), identities (Richards, Pillay, Mazodze & Govere, 2005), and attitudes toward colonizing countries (David & Okazaki, 2010). Although it might be expected that attitudes would be more positive toward people from countries with mutual/peer influence and more negative toward people from countries with imperialist/dominating influence, this may not be the case. Some past research has found evidence of an internalized “colonial mentality,” such that some Filipino Americans have an implicit preference for American over Filipino things (David & Okazaki, 2010). Some social scientists in Colombia have also pointed out that, while Latin American societies combated colonialism, they also adopted important aspects of Western culture, such as belief and value systems, as their own (Mansilla, 2004), which may affect how they treat individuals from different groups (Maya Restrepo, 2009). Yet, empirical evidence on how these dynamics may affect attitudes toward people from different countries is missing. Therefore, these potential differences between countries based on type and level of influence are important to explore when examining attitudes toward people from other countries and immigrants in a place like Colombia.

Polyculturalism

Historians introduced the concept of polyculturalism, documenting examples of ways that different racial and ethnic groups have throughout history interacted, exchanged ideas, and influenced each other’s cultures (e.g., Flint, 2006; Kelley, 1999; Prashad, 2001). As an example, in his book Everybody was Kung Fu fighting: Afro-Asian connections and the myth of cultural purity, Prashad (2001) describes the pan-Asian, pan-African, and other cultural influences that have contributed to Kung Fu, which is often thought of as a solely East Asian cultural product. There are indeed endless examples of these types of cultural influences or exchanges that have occurred all around the world and in all realms of life, ranging from martial arts and music to food and science.

Inspired by the work of these historians (Flint, 2006; Kelley, 1999; Prashad, 2001), we began a research program from a psychological perspective studying polyculturalism as a belief system (Rosenthal & Levy, 2010; 2012). Although polyculturalism is not a lay person’s term, there are many examples of cross-cultural influences that people are aware of, potentially even more so in our increasingly globalized world. For example, in Colombia, a person who endorses polyculturalism might think of the examples of cumbia and salsa, which are popular styles of music and dance in Colombia derived from African, Indigenous American, and European influences as well as influences from surrounding countries in South, Central, and North America, and the Caribbean. This kind of information may be taught in schools, passed on by family and other community members, or expressed in media. This attention to cross-cultural influences and connections as well as the dynamic nature of cultures is not only historically and contemporarily accurate, but also offers a lens through which people can potentially see past perceived cultural “barriers” between groups of people and envision social change and innovation not constrained by concepts of cultures as bounded, separate, and static. Therefore, we hypothesized that endorsement of polyculturalism could support positive intergroup attitudes and behaviors by highlighting dynamic connections among different racial, ethnic, and cultural groups (Rosenthal & Levy, 2010, 2012). Being aware of the ways that one’s own culture has both been influenced by and has influenced other cultures could increase openness to intergroup contact and greater comfort interacting with people of other backgrounds. Likewise, seeing how everywhere diverse groups of people have made contributions to cultural products that people enjoy and benefit from could promote more positive attitudes toward people from other groups and encourage greater support for social equality.

To empirically study polyculturalism as a belief system, we (Rosenthal & Levy, 2012) developed an individual difference measure assessing the extent to which people acknowledge the often unspoken connections between different racial, ethnic, and cultural groups and the interactions between different groups that have led and continue to lead to various cultural products. Importantly, endorsement of polyculturalism is distinct from other diversity-related belief systems, which we have empirically demonstrated (Bernardo et al., 2016; Rosenthal & Levy, 2012). Belief in polyculturalism does not involve minimizing or ignoring group differences —such as with colorblindness (Ryan, Hunt, Weible, Peterson & Casas, 2007; Wolsko, Park, Judd & Wittenbrink, 2000)— or prescribing that members of diverse cultural backgrounds adopt a dominant culture —such as with assimilation (Verkuyten, 2005; Zárate & Shaw, 2010). However, belief in polyculturalism does involve attending to the dynamic nature of intercultural interactions and the products of those interactions, therefore not focusing only on the unique cultural differences between groups (such as with multiculturalism), which can sometimes lead to stereotyping and enhancement of perceived divisions between groups (Ryan et al., 2007; Wolsko et al., 2000). It is an important feature to the context of Colombia that the belief in polyculturalism also does not involve a promotion of the homogenization of diverse cultures —such as with mestizaje (Telles & Bailey, 2013). Scholars argue that since Colonial times, Latin American ideologies of mestizaje, or racial mixing, mask ethno-racial discrimination. In Colombia, at first, colonial narratives put together the notion of “the Indigenous”, thus reducing several Indigenous cultures to one overarching category, ignoring the existing differences between them. Later, multiple African ethnicities were reduced to a single one: Black, or Negro in Spanish (Hering Torres, 2012). Consequently, although having a focus on culture mixing, mestizaje ideologies in reality constituted a “racial project” that forced the assimilation of Indigenous populations and ignored descendants of formerly enslaved African peoples (Telles & Bailey, 2013). Polyculturalism is a unique belief system or approach to diversity because it allows for the acknowledgement and appreciation of cultural differences while also focusing on cross-cultural connections and influences, which we hypothesized would have positive associations with intergroup attitudes and behaviors.

Supporting our hypotheses, we have found endorsement of polyculturalism to be associated with a range of more positive intergroup attitudes across many diverse undergraduate and community samples in the us. Polyculturalism has been associated with less support for social inequality, more positive attitudes toward diversity, greater willingness for intergroup contact, and greater support for liberal policies related to affirmative action and immigration (Rosenthal & Levy, 2012). Polyculturalism has also been associated with more positive and less negative attitudes toward Muslim Americans, including willingness for intergroup contact and relevant policy attitudes (Rosenthal, Levy, Katser, & Bazile, 2015). Further, among undergraduates at a diverse university, polyculturalism before starting college prospectively predicted increases in positive intergroup contact and friendship from first to second year of college (Rosenthal & Levy, 2016), supporting the connection between polyculturalism and openness to cross-cultural contact and influence. Other research in the us has found polyculturalism to be associated with less sexism (Rosenthal, Levy, & Militano, 2014) and sexual prejudice —i.e., prejudice toward gay men and lesbian women (Rosenthal, Levy, & Moss, 2012)—, as well as with lower intergroup anxiety and greater belonging among undergraduates at a diverse university (Rosenthal, Levy, London, & Lewis, 2016).

Although the first psychological research on polyculturalism was conducted in the us, polyculturalism is a belief system relevant to societies and cultures all around the world, and increasing research has been exploring polyculturalism outside the us. We have found that, among students in the Philippines and the us, endorsement of polyculturalism is associated with more positive attitudes toward people from other countries as well as greater willingness to be friends with people from other countries who move to their country (Bernardo Rosenthal, & Levy, 2013). In another study with a Filipino university sample, endorsement of polyculturalism was associated with greater warmth toward gay men and lesbian women (Bernardo, 2013), consistent with findings from us samples described above (Rosenthal, Levy, & Moss, 2012). Studies with Australian adults have also found endorsement of polyculturalism to be associated with less support for discrimination against a Muslim woman (described in a scenario), greater support for the celebration of “Harmony Day,” which is focused on exploring cultural diversity (Pedersen, Paradies & Barndon, 2015), as well as lower prejudice toward refugees, lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals, and transgender and intersex individuals (Healy, Thomas & Pedersen, 2017). Additionally, a cross-cultural study with university students in Australia and China found polyculturalism to be associated with greater cultural intelligence (Bernardo & Presbitero, 2017). These findings support that polyculturalism is a relevant belief system in other places besides the us, with implications for a range of intergroup attitudes, including attitudes toward people from other countries. They also suggest that further research examining polyculturalism and its correlates in different places around the world is warranted, and the study of polyculturalism may shed light on intercultural dynamics in Colombia.

The Current Research

In the current research, we explored associations of polyculturalism in Colombia with attitudes toward people from other countries. We hypothesized that, consistent with past work in the Philippines and the us, endorsement of polyculturalism would be associated with more positive attitudes toward people from other countries and friendship intentions toward immigrants moving from other countries to Colombia.

In order to increase confidence that polyculturalism makes a unique contribution to attitudes and friendship intentions, we controlled for social dominance orientation (level of support for social hierarchy and inequality) and national identification because of their established influence on and relevance to intergroup attitudes cross-culturally (Brylka, Mähönen & Jasinskaja-Lahti, 2015; Pratto et al., 2000). Specifically, social dominance orientation (Thomsen, Green & Sidanius, 2008) and national identification (Pehrson, Vignoles & Brown, 2009) have been associated with negative attitudes and intentions toward immigrants. In some (Rosenthal & Levy, 2012) but not in all (Bernardo, Rosenthal, & Levy, 2013) past research, we have found polyculturalism to be negatively associated with social dominance orientation; in some but not other past samples (Bernardo, Rosenthal, & Levy, 2013), we have found polyculturalism to be positively associated with national identification. We also previously found social dominance orientation to be negatively associated with attitudes toward people from other countries and immigrants (Bernardo, Rosenthal, & Levy, 2013). We additionally controlled for feelings toward the self, given self-esteem’s relevance to intergroup attitudes (Aberson, Healy & Romero, 2000; Hogg & Abrams, 1990), as well as to avoid potential confounding of associations by mood. Although we have not found feelings toward the self to be associated with polyculturalism, we have found them to be associated positively with friendship intentions toward immigrants (Bernardo, Rosenthal, & Levy, 2013).

We also explored whether intercultural attitudes and intentions, as well as their associations with polyculturalism, varied for different countries based on type and level of cultural influence. In particular, we made comparisons between Western countries that have had imperialist/dominating and high levels of political, economic, and cultural influence on Colombia (Spain, the us, the uk), neighboring countries that share common history with Colombia and have had mutual/peer and high levels of influence on the country (Ecuador and Venezuela), and countries that have had relatively low direct influence on Colombia (Afghanistan, Canada, Japan, North Korea, and the Philippines). Further, we tested whether social dominance orientation and national identification might moderate associations of polyculturalism with attitudes and friendship intentions, as social dominance orientation has been found to interact with other factors to predict intergroup attitudes (Federico, 1999), and we have found ethnic identification to moderate some associations of polyculturalism with intergroup attitudes in the U.S. (Rosenthal, Levy, & Moss, 2012). Although we did not have specific hypotheses that country group, social dominance orientation, or ethnic identification would moderate associations of polyculturalism with attitudes or friendship intentions, past research suggests that these factors are relevant potential moderators.

Exploring these possible interactions is important to understand the nature of polyculturalism’s associations with attitudes and friendship intentions. Taken together, the current study aimed to build on and extend past research on polyculturalism, examining its role in Colombia (and Latin America, more broadly) for the first time, and to contribute to an understanding of intercultural attitudes in Colombia.

Method

Participants

Individuals had to be 18 years or older to be eligible to participate. A total of 446 adults took part in the study. Results reported below are based on data from 423 individuals that were born in Colombia (12 people not born in Colombia and 3 people who did not report were excluded) and who completed all measures of interest for the current research —8 people with missing data were excluded. Of those 423 participants, 226 (53 %) were men, 195 (46 %) women, and 2 did not report their gender. The mean age of participants was 27.21 (SD = 10.55). The majority of participants (241, 57%) identified as combined indigenous and white descent (Mestizo), 120 (28 %) identified as white, 29 (7 %) as of black and white descent (Mulatto), 8 (2 %) as indigenous, 4 (1 %) as black/Afro-Colombian, 4 (1 %) as black and indigenous, and 17 (4 %) identified as belonging to another race/ethnicity or did not report their race/ethnicity. As for social class, 10 (2 %) participants identified as lower class, 47 (11 %) as lower middle class, 269 (64 %) as middle class, 83 (20 %) as upper middle class, 7 (2 %) as upper class, and 7 participants did not report their social class. In terms of education level, 8 (2 %) participants reported having finished primary school, 109 (25.8 %) reported having finished high school, 63 (15 %) reported having completed a technical school, 215 (51 %) having completed a university degree, and 21 (5 %) reported finishing a Master’s or other higher postgraduate degree.

Procedure

In 2011, for this study community adults were recruited in different areas of Bogotá Colombia, in public places, such as parks, malls, and bus terminals. People were invited to participate in the study by undergraduate research assistants who were trained to use a script for recruitment that involved introducing themselves as research assistants for a project about social beliefs. Potential participants were given a written consent letter to read, and research assistants highlighted that participation was voluntary and anonymous, they could stop participation at any time, and there would be no payment for participation. If they verbally consented to participate, they were given paper-and-pencil surveys, which were in Spanish. Research assistants gave participants some space to complete surveys in private, but remained close enough so that they could be called on to answer any questions. Procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Universidad del Rosario.

Measures

As part of a larger survey, participants completed the following established measures, for which mean scores were calculated.

Polyculturalism: Participants completed the established 5-item measure of polyculturalism —e.g., “Different racial, ethnic, and cultural groups influence each other” (Rosenthal & Levy, 2012) on a scale of 1 (Strongly disagree) to 6 (Strongly agree) (α = .82).

Social dominance orientation: Participants completed a 7-item, a shortened version previously used (Levy, West, Ramirez & Karafantis, 2006; Bernardo, Rosenthal, & Levy, 2013) of the social dominance orientation scale —e.g., “Some groups of people are simply not the equal of others” (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth & Malle, 1994)— on a scale of 1 (Strongly disagree) to 6 (Strongly agree) (α = .74).

National identification: Participants completed a 4-item, adapted version previously used (Bernardo, Rosenthal, & Levy, 2013) of a patriotism/nationalism measure —e.g., “I am proud to be Colombian” (Kosterman & Feshbach, 1989) on a scale of 1 (Strongly disagree) to 6 (Strongly agree) (α = .88).

Feelings toward the self: Participants completed a previously used 2-item measure of how positive participants felt about themselves (Levy et al., 2006; Bernardo, Rosenthal, & Levy, 2013). One item involved choosing which face from several options (ranging from a big frown to a big smile) that best reflected how participants felt about themselves at that moment, and the other item involved choosing which phrase on a scale of 1 (Not at all good) to 6 (Very, very good) best reflected how they felt about themselves at that moment (α = .85).

Attitudes toward people from other countries: Participants completed the established thermometer scales (Herek & Capitanio, 1999; Louis, Esses, & Lalonde, 2013), indicating how warm or cold they feel toward individuals from ten countries (Bernardo, Rosenthal, & Levy, 2013) on a scale of 0 (Cold) to 100 (Warm). The ten countries included were Afghanistan, Canada, Ecuador, England, Japan, North Korea, the Philippines, Spain, the United States, and Venezuela (α = .95).

Friendship intentions toward immigrants: Participants completed nine items previously used (Bernardo, Rosenthal, & Levy, 2013) indicating on a scale from 1 (Not at all willing) to 6 (Very willing) how willing they would be to be friends with someone who moved to their country from the same set of countries asked about in the attitudes measure, except for the Philippines was left out of the survey inadvertently (α = .91).

Data Analysis

We used correlations, t-tests, and an analysis of variance (anova) to test if age (continuous), social class (continuous), gender (dichotomous), education level (dichotomized as primary school, high school, or technical degree versus university degree or Master’s or higher degree), or race/ethnicity (categorized as white, indigenous and white/Mestizo, or all other racial/ethnic groups) were associated with endorsement of polyculturalism. To test the hypotheses that polyculturalism would be associated with more warm or positive attitudes toward people from other countries and greater friendship intentions toward immigrants, we conducted two step-wise linear regression analyses (to test the unique variance accounted for by polyculturalism), one for each outcome variable. In Step 1, we entered the control variables of social dominance orientation, national identification, and feelings toward the self. In Step 2, we entered polyculturalism. To explore differences in attitudes and friendship intentions toward people from different groups of countries based on level and type of cultural influence, we conducted two repeated-measures anovas, one for each outcome variable, comparing means between Western countries that have had high levels of influence on Colombia (Spain, the us, the uk), countries that neighbor Colombia (Ecuador and Venezuela), and countries that have had less direct influence on Colombia (Afghanistan, Canada, Japan, North Korea, and the Philippines). To explore whether group of countries moderated associations of polycuturalism with attitudes and friendship intentions, we conducted two mixed anovas, one for each outcome variable. In these analyses, polyculturalism and control variables were treated as between-subjects variables, and group of countries was treated as a within-subjects variable. Finally, to test whether social dominance orientation or national identification moderated associations of polyculturalism with attitudes and friendship intentions, we conducted four step-wise linear regression analyses, two for each outcome variable, and two for each moderator. In these analyses, all controls were included, mean centered main effects for polyculturalism and the moderator were also included, and the interaction effect between the mean centered versions of polyculturalism and the moderator were included as predictors of each outcome.

Results

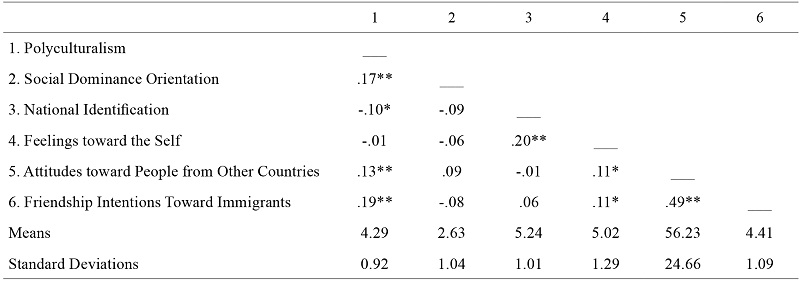

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations for main study variables are shown in Table 1. The mean for polyculturalism was on the “Agree”-side of the scale (between “Agree a little bit” and “Agree”), indicating on average that participants endorsed the belief that different racial and ethnic groups interact with, influence, and are connected to each other. Endorsement of polyculturalism was not associated with age, social class, gender, or race/ethnicity, but was associated with education level, t (414) = -3.09, p = .002. Participants with a university, Master’s, or higher degree (M = 4.42, SD = 0.78) endorsed polyculturalism more than those with a primary, high school, or technical degree did (M = 4.14, SD = 1.06).

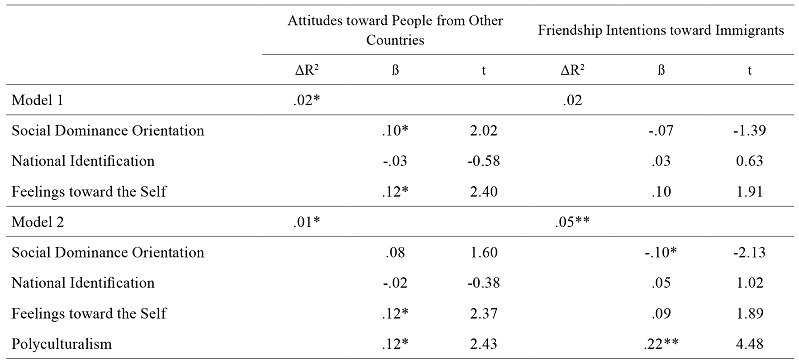

As hypothesized, polyculturalism was positively correlated with attitudes toward people from other countries and friendship intentions toward immigrants from other countries who move to Colombia. Further, in regression analyses (see Table 2), while controlling for social dominance orientation, national identification, and feelings toward the self, greater endorsement of polyculturalism remained associated with more positive attitudes and greater friendship intentions toward people from other countries.

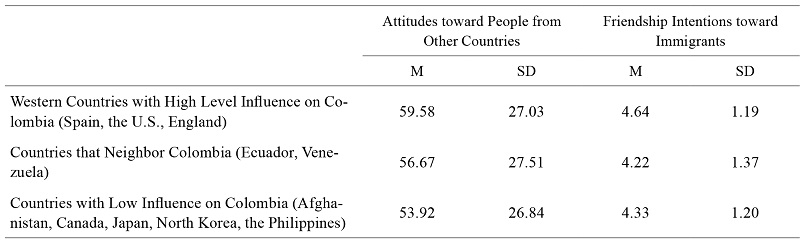

The repeated measures anova comparing attitudes toward people from other countries based on group of countries was significant, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.90, F(2, 417) = 24.11, p < .001, ηp 2 = .10. Sidak pairwise post-hoc comparisons were all significant (ps all < .03). The pattern of means (see Table 3) revealed that attitudes were most positive toward individuals from Western countries that have had a high level of influence on Colombia, around the middle toward individuals from countries that neighbor Colombia, and lowest toward individuals from countries that have had less direct influence on Colombia. The repeated measures anova comparing friendship intentions toward people from other countries based on group of countries was also significant, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.87, F(2, 421) = 32.65, p < .001, ηp 2 = .13. Sidak pairwise post-hoc comparisons revealed significant differences between Western countries that have had a high level of influence on Colombia and both other country groups (ps < .001), but no difference between countries that neighbor Colombia and countries that have had less direct influence on Colombia (p = .109). The pattern of means (see Table 3) revealed that friendship intentions were highest toward individuals from Western countries that have had a high level of influence on Colombia, around the middle toward individuals from countries that have had less direct influence on Colombia, and lowest toward individuals from countries that neighbor Colombia.

The two mixed anovas found that group of countries did not moderate the associations of polyculturalism with attitudes, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.99, F(2, 413) = 2.34, p = .106, ηp 2 = .01, or friendship intentions, Wilks’ Lambda = 0.99, F(2, 417) = 1.22, p = .297, ηp 2 = .01. The two regression analyses testing social dominance orientation as a moderator of the associations of polyculturalism with attitudes and friendship intentions found nonsignificant interactions (ß = .01, t = 0.11, p = .915 for attitudes; ß = -.04, t = -0.74, p = .463 for friendship intentions). Similarly, the two regression analyses testing national identification as a moderator of the associations of polyculturalism with attitudes and friendship intentions found nonsignificant interactions (ß = .01, t = 0.24, p = .809 for attitudes; ß = .05, t = 0.94, p = .346 for friendship intentions).

Discussion

This study contributes to filling the gap in research on lay belief systems about cross-cultural influences and attitudes toward people from other countries in Latin America, a region of the world with significant and changing migration patterns (Donato et al., 2010). In particular, we found that our sample of adults born and living in Colombia, a country with a long history of cross-cultural contact and influence and with recent increasing rates of immigration, generally endorsed polyculturalism, which was associated with more positive attitudes toward people from other countries and greater friendship intentions toward immigrants from other countries who move to one’s own country. These findings are consistent with past work finding polyculturalism to be associated with more positive intergroup attitudes and behaviors in Australia, the Philippines, and the us (Rosenthal et al., 2012a, 2012b, 2014, 2015, 2016a, 2016b; Healy et al., 2017; Pederson et al., 2015), and this is the first study to examine the implications of polyculturalism anywhere in Latin America. These findings add to growing evidence that polyculturalism has positive intergroup implications across different regions of the world. Comparing endorsement of polyculturalism in the current study to our similar prior studies in the Philippines and us (Bernardo, Rosenthal, & Levy, 2013), endorsement was slightly lower in the current sample (mean closer to “Agree” in the Philippines and the us, while closer to “Agree a little” in Colombia). However, in the current sample, endorsement of polyculturalism was higher among participants with a university or graduate degree than those with a primary, high school, or technical degree, considering that the prior Filipino and us samples consisted of university students.

We also found that people’s attitudes and friendship intentions were the most positive toward people from Western countries that have had a high level of and imperialist/dominating influence on Colombia, including Spain, the us, and the uk. Attitudes were the coldest/the least warm toward people from countries that have had less influence on Colombia, including Afghanistan, Canada, Japan, North Korea, and the Philippines. However, friendship intentions were lowest toward people from countries that neighbor and have had mutual/peer influence on Colombia, including Ecuador and Venezuela, although friendship intentions toward neighboring countries and countries with less influence on Colombia did not differ significantly. That the Western countries were rated higher than the others on both of these measures may reflect some form of system justification or internalized “colonial mentality,” such as that people from formerly colonized countries may still behave in ways that are consistent with beliefs and values from the colonizing/dominating countries and view things and people from those colonizing/dominating countries more positively than things and people from other countries (David & Okazaki, 2010; Longxi, 2013; Mansilla, 2004). The fact that attitudes were warmer/less cold toward neighboring countries than countries with less influence is consistent with the expectation that positive attitudes toward neighboring countries would result from them sharing common history with and having mutual/peer and high levels of influence on Colombia. That friendship intentions were the lowest toward neighboring countries is unexpected but may reflect the political tensions that existed between the governments of Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela at the time of data collection (Echavarria, 2013). However, given that the difference in friendship intentions between neighboring countries and countries with less influence was not significant, this should be interpreted with caution and explored more in future research. Despite these mean differences, group of countries did not moderate the associations of polyculturalism with attitudes or friendship intentions. This suggests that the implications of polyculturalism for attitudes toward people from other countries are consistent in Colombia, regardless of the type or level of cultural influence from those countries or mean differences in attitudes toward people from those countries.

Social dominance orientation and national identification also did not moderate polyculturalism’s associations with attitudes or friendship intentions. This further supports that the implications of polyculuralism for intercultural attitudes in Colombia are consistent, regardless of the individuals’ level of support for group inequality or identification with the own nationality. This is notable given that social dominance orientation (Thomsen, Green & Sidanius, 2008) and the national identification (Pehrson, Vignoles, & Brown, 2009) have been associated with negative attitudes and intentions toward immigrants specifically, suggesting polyculturalism may be a belief that can overcome other system-justifying beliefs. Further, most sociodemographic variables, including age, social class, gender, and race/ethnicity were not associated with endorsement of polyculturalism. All of these findings, along with past findings, support that polyculturalism is a generalized belief system that has implications for people’s attitudes toward other groups, including people from other countries. The one sociodemographic variable found to be associated with endorsement of polyculturalism was the education level, as participants with university or graduate degrees endorsed polyculturalism more than those with primary, high school, or technical degrees. This may indicate that in university and graduate education, information about historical and contemporary cross-cultural exchanges and influences is taught more than in other educational settings. It is also possible that in university and graduate education, students have greater opportunities to experience cross-cultural contact and influence, thereby increasing their endorsement of polyculturalism.

Limitations, Future Directions, and Implications

The current research was cross-sectional and correlational, limiting the ability to determine direction of effects and any potential changes over time in endorsement of polyculturalism. Future work that continues to explore polyculturalism using different methodologies (e.g., experimental, longitudinal, qualitative) will be helpful to continue to illuminate the role of this belief system in intergroup dynamics. Participants were also not asked to report their prior level of contact with people from other countries and/or immigrants to Colombia. In future studies, this is important to explore, as intergroup contact is known to affect intergroup attitudes (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008). Other sociodemographic variables that were not assessed, such as occupation and income level, might also be explored in connection with these attitudes and polyculturalism in future research. Although polyculturalism has been distinguished from other relevant constructs like multiculturalism, colorblindness, and assimilation in past studies (Rosenthal & Levy, 2012), these beliefs were not assessed and compared to polyculturalism in the current research, issues which would be worthwhile to explore in larger studies conducted in the future in Colombia and other places. Another relevant construct for future work to consider in comparison to polyculturalism is cosmopolitanism, which has been conceptualized in many ways (Cleveland, Laroche, Takahashi & Erdoğan, 2014). In recent research in psychology, cosmopolitan orientation has been defined as including cultural openness, global prosociality, and respect for cultural diversity (Leung, Koh, & Tam, 2015). Future work might explore if polyculturalism and cosmopolitan orientation are distinct or allied beliefs, or if polyculturalism predicts cosmopolitan orientation, as we have previously found polyculturalism to predict greater interest in, appreciation for, and comfort with diversity (Rosenthal & Levy, 2012). Further, polyculturalism’s associations with attitudes toward people from other countries and friendship intentions toward immigrants were small, account for 1 % and 5 % of unique variance in these outcomes, respectively. Thus, polyculturalism is not the only relevant construct needed to understand these attitudes and intentions. However, given the complexity and multifaceted nature of dynamics contributing to attitudes toward people from other countries and immigrants, and given that polyculturalism contributes to a unique variance in these outcomes while accounting for other well-known predictors of these attitudes, these findings underscore that polyculturalism is one important factor among various others that help us to understand these attitudes and potentially shed light on how we can intervene to improve them.

Given the dearth of research in this area along with the rich diversity and recent changing trends in immigration in Colombia as well as in other countries in Latin America, future work could build on the current findings to further understand intercultural attitudes in this region of the world. For example, future work might explore the implications of polyculturalism for attitudes toward different groups living within Colombia or other countries in Latin America, which may be similar or different to the implications for attitudes toward people from other countries. As described earlier, mestizaje ideologies have constituted a deliberate policy in Colombia and other parts of Latin America (Telles & Bailey, 2013). Those ideologies are relevant to cross-cultural influences, as they promote racial and cultural mixing, but in doing so they have also promoted the homogenization of diverse cultures and the masking of persistent racial discrimination and hierarchies, thus becoming an example of inclusionary discrimination (Peña, Sidanius, & Sawyer, 2004). Further, the history of colonization and slavery that is inherently a part of the history of intercultural contact in Colombia, as well as in many other countries, can play a role in the people’s endorsement of polyculturalism and the implications of that endorsement for other intergroup attitudes. Additionally, since data from the current study were collected in 2011, it did not assess the present immigration from Venezuela that has increased and has come to be perceived as a public problem, with organizations highlighting the importance of creating public policy in solidarity with Venezuelan immigrants to prevent economic exploitation of and xenophobia toward these individuals (El Heraldo, 2017). Thus, more work on these attitudes in Colombia is currently needed. Our findings also suggest that intergroup attitudes can vary depending on different types and amounts of intercultural interactions, yet the associations of polyculturalism with intergroup attitudes are not moderated by those interaction differences. Future studies to examine polyculturalism in other regions of the world can also further illuminate the role of this belief system in intergroup dynamics in various cultural contexts. It will be important for future research to explore whether endorsement of polyculturalism and its correlated with different types of intergroup attitudes and behaviors vary depending on cultural, political, and social contexts in different parts of the world.

With globalization, there are also still unfortunately numerous examples of negative interactions between various different countries and groups of people, although positive interactions and products of cross-cultural influences may also be more readily apparent. The measure of polyculturalism that has been used in all empirical studies of polyculturalism to date does not assess whether people view cross-cultural connections and influences positively or negatively, nor does it distinguish between more positive or negative contexts for those connections and influences. Future work may benefit from further teasing apart endorsement of polyculturalism in these ways and exploring how this belief system interacts with other belief systems and unique contexts in Colombia as well as other countries, including economic, political, and power dynamics between countries that play an important role in globalization. Further, there are some limitations to other measures used, such as only two items to assess feelings toward the self, a shortened version of the social dominance orientation scale, and a relatively short measure of friendship intentions toward immigrants. Future work should test these findings with other longer, established measures of these constructs.

The current along with past findings, including recent experimental evidence that priming polyculturalism can improve attitudes toward visitors from other countries accommodating their behavior to local norms and can increase preference for experiences that involve cultural mixes (Cho, Morris & Dow, 2017; Cho, Morris, Slepian & Tadmor, 2017), suggest that polyculturalism could be used in interventions to improve intergroup attitudes, including toward people from other countries and immigrants. This may be particularly relevant in light of recent calls for efforts to prevent xenophobia toward Venezuelan immigrants to Colombia. We (Rosenthal & Levy, 2010) have previously discussed the potential to combine polyculturalism with strengths of other diversity approaches, such as multiculturalism, in programs, policies, and curricula in educational and work settings. Findings from the current investigation suggest that in Colombia, polycultural messages may be stronger in university settings than in earlier school contexts, suggesting that messages about historical and contemporary cross-cultural contact and influences may be important to infuse more into primary and high school education. These and other possible applications deserve attention and testing in future research.

Conclusion

We found that endorsement of polyculturalism is related to more positive attitudes toward people from other countries among adults in Colombia, a country in Latin America with a diverse history and current increasing rates of immigration. Given the increasing globalization and growing evidence that polyculturalism has positive associations with intergroup attitudes and behaviors for people in different parts of the world, further study of polyculturalism is warranted and may enhance our current understandings of the psychology of intercultural relations.

References

Aberson, C. L., Healy, M., & Romero, V. (2000). Ingroup bias and self-esteem: a meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4, 157-173. Doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0402_04

Bernardo, A. B. I. (2013). Exploring social cognitive dimensions of sexual prejudice in Filipinos. Philippine Journal of Psychology, 46, 19-48.

Bernardo, A. B. I., Rosenthal, L., & Levy, S. R. (2013). Polyculturalism and attitudes toward people from other countries. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37, 335-344.

Bernardo, A. B. I., Salanga, M. G. C., Tjipto, S., Hutapea, B., Yeung, S. S., & Khan, A. (2016). Contrasting lay theories of polyculturalism and multiculturalism: Associations with essentialist beliefs of race in six Asian cultural groups. Cross-Cultural Research, 50, 231-250.

Bernardo, A. B. I., & Presbitero, A. (2017). Belief in polyculturalism and cultural intelligence: Individual- and country-level differences. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 307-310.

D’Anglejan, S. (2009). Migraciones internacionales, crisis económica mundial y políticas migratorias. ¿Llegó la hora de retornar? Oasis, (14), 7-36.

Brylka, A., Mähönen, T. A., & Jasinskaja-Lahti, I. (2015). National identification and intergroup attitudes among members of the national majority and immigrants: preliminary evidence for the meditational role of psychological ownership of a country. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 3, 24-45. Doi: 10.5964/jspp.v3i1.275

Cabieses B., Tunstall H., Pickett K.E., & Gideon J. (2013). Changing patterns of migration in Latin America: How can research develop intelligence for public health? Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 34, 68-74.

Chiu, C.-Y., Gries, P., Torelli, C. J., & Cheng, S. Y. Y. (2011). Toward a social psychology of globalization. Journal of Social Issues, 67, 663-676. Doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01721.x

Cho, J., Morris, M. W., & Dow, B. (2017). How do the Romans feel when visitors “do as the Romans do”? Diversity ideologies and trust in evaluations of cultural accommodation. Academy of Management Discoveries. Epud ahead of print. Doi: 10.5465/amd.2016.0044

Cho, J., Morris, M. W., Slepian, M. L., & Tadmor, C. T. (2017). Choosing fusion: The effects of diversity ideologies on preference for culturally mixed experiences. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 69, 163-171. Doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2016.06.013

Cleveland, M., Laroche, M., Takahashi, I., & Erdoğan, S. (2014). Cross-linguistic validation of a unidimensional scale for cosmopolitanism. Journal of Business Research, 67, 268-277. Doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.05.013

David, E. J. R., & Okazaki, S. (2010). Activation and automaticity of colonial mentality. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 40, 850–887. Doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00601.x

Donato, K. M., Hiskey, J., Duran, J., & Massey, D. (2010). Continental divides: International migration in the Americas. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science Series.

Echavarría, J. (2013). Identity categories constructed and produced by the Democratic Security Policy. In In/security in Colombia: Writing political identities in the democratic security policy. Manchester University Press: UK.

El Heraldo. (2017). iom llama a Colombia a prevenir xenofobia contra venezolanos. Retrieved from https://www.elheraldo.co/mundo/oim-llama-colombia-prevenir-xenofobia-contra-venezolanos-379149

Federico, C. M. (1999). The interactive effects of social dominance orientation, group status, and perceived stability on favoritism for high-status groups. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 2, 119-143. Doi: 10.1177/1368430299022002

Flint, K. (2006). Indian-African encounters: polyculturalism and African therapeutics in Natal, South Africa, 1886-1950s. Journal of Southern African Studies, 32, 367-385.

Gómez, M. (2009). Colombian migration policy at the early 20th century. Memoria y Sociedad, 13(26), 7-17.

Harris, R. L., & Nef, J. (2008). Capital, power, and inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Healy, E., Thomas, E., & Pedersen, A. (2017). Prejudice, polyculturalism, and the influence of contact and moral exclusion: A comparison of responses toward lgbi, ti, and refugee groups. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 47, 389-399.

Herek, G.M., & Capitanio, J. C. (1999). Sex differences in how heterosexuals think about lesbians and gay men: evidence from survey context effects. Journal of Sex Research, 36, 348-360. Doi: 10.1080/00224499909552007

Hering Torres, M.S. (2012). Sombras y ambivalencias de la igualdad y la libertad (Shadows and ambivalences of equality and freedom). In B. Tovar Zambrano (Ed.), Independencia, historia diversa (Independece, a diverse story) (pp. 443-477). Bogota: Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

Hogg, M. A., & Abrams, D. (1990). Social motivation, self-esteem and social identity. In D. Abrams & M. A. Hogg (Eds.), Social identity theory: Constructive and critical advances. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Kelley, R. D. G. (1999). The people in me. Utne Reader, 95, 79-81.

Kosterman, R., & Feshbach, S. (1989). Toward a measure of patriotic and nationalistic attitudes. Political Psychology, 10, 257-274. Doi: 10.2307/3791647

Leung, A. K.-Y., Koh, K., & Tam, K.-P. (2015). Being environmentally responsible: Cosmopolitan orientation predicts pro-environmental behaviors. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 43, 79-94. Doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.05.011

Levy, S. R., West, T., Ramirez, L., & Karafantis, D. M. (2006). The Protestant work ethic: a lay theory with dual intergroup implications. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 9, 95-115. Doi: 10.1177/1368430206059874

Longxi, Z. (2013). Reflections on colonialism and coloniality. Localities, 3, 203-209.

Louis, W. R., Esses, V. M., & Lalonde, R. N. (2013). National identification, perceived threat, and dehumanization as antecedents of negative attitudes toward immigrants in Australia and Canada. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43, E156-E165. Doi: 10.1111/jasp.12044

Mansilla, H. F. (2004). Las mentalidades sociales y el nivel del preconsciente colectivo en el Tercer Mundo. Espacio Abierto Cuaderno Venezolano de Sociología, 13, 521-532.

Maya Restrepo, L. A. (2009). Racismo institucional, violencia y políticas culturales. Legados coloniales y políticas de la diferencia en Colombia. Historia Critica, 218-245.

Migración Colombia–oim (2013). Caracterización sociodemográfica y laboral de los trabajadores temporales extranjeros en Colombia: Una mirada retrospectiva. Retrieved from: https://www.oim.org.co/publicaciones-oim/migracion-internacional/2574-caracterizacion-sociodemografica-y-laboral-delos-trabajadores-temporales-extranjeros-en-colombia-una-mirada-retrospectiva.html

Moghaddam, F. M. (2012). The omnicultural imperative. Culture and Psychology, 18, 304-330. Doi: 10.1177/1354067X12446230

oim (2012). Perfil migratorio de Colombia 2012. Retrieved from: https://www.oim.org.co/publicaciones-oim/migracion-internacional/2576-perfil-migratorio-de-colombia-2012.html

Pedersen, A., Paradies, Y., & Barndon, A. (2015). The consequences of intergroup ideologies and prejudice control for discrimination and harmony. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 45, 684-696. Doi: 10.1111/jasp.12330

Pehrson, S., Vignoles, V. L., & Brown, R. (2009). National identification and anti-immigrant prejudice: Individual and contextual effects of national definitions. Social Psychology Quarterly, 72(1), 24-38. Doi: 10.1177/019027250907200104

Peña, Y., Sidanius, J., & Sawyer, M. (2004). Racial democracy in the Americas: A Latin and us comparison. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35, 749-762. Doi: 10.1177/0022022104270118

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2008). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 751-783.

Prashad, V. (2001). Everybody was Kung Fu fighting: Afro-Asian connections and the myth of cultural purity. Boston: Beacon Press.

Pratto, F., Liu, J. H., Levin, S., Sidanius, J., Shih, M., Bachrach, H., & Hegarty, P. (2000). Social dominance orientation and the legitimization of inequality across cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31, 369-409. Doi: 10.1177/0022022100031003005

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 741-763. Doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.741

Richards, K. A. M., Pillay, Y., Mazodze, O., & Govere, A. S. (2005). The impact of colonial culture in South Africa and Zimbabwe on identity development. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 15, 41-51.

Rosenthal, L., & Levy, S. R. (2010). The colorblind, multicultural, and polycultural ideological approaches to improving intergroup attitudes and relations. Social Issues and Policy Review, 4, 215-246.

Rosenthal, L., & Levy, S. R. (2012). The relation between polyculturalism and intergroup attitudes among racially and ethnically diverse adults. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18, 1-16.

Rosenthal, L., Levy, S.R., & Moss, I. (2012). Polyculturalism and openness about criticizing one’s culture: Implications for sexual prejudice. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 15, 149-166.

Rosenthal, L., Levy, S. R., & Militano, M. (2014). Polyculturalism and sexist attitudes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38, 519-534.

Rosenthal, L., Levy, S. R., Katser, M., & Bazile, C. (2015). Polyculturalism and attitudes toward Muslim Americans. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 21, 535-545.

Rosenthal, L., & Levy, S. R. (2016a). Polyculturalism predicts increased positive intergroup contact and friendship across the beginning of college. Journal of Social Issues, 72, 472-488.

Rosenthal, L., Levy, S. R., London, B., & Lewis, M. A. (2016b). Polyculturalism among undergraduates at diverse universities: Associations through intergroup anxiety with academic and alcohol outcomes. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 16, 193-226.

Ryan, C. S., Hunt, J. S., Weible, J. A., Peterson, C. R., & Casas, J. F. (2007). Multicultural and colorblind ideology, stereotypes, and ethnocentrism among black and white Americans. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 10, 617-637. Doi: 10.1177/1368430207084105

Telles, E., & Bailey, S. (2013). Understanding Latin American beliefs about racial inequality. American Journal of Sociology, 118, 1559-1595. Doi: 10.1086/670268

Thomsen, L., Green, E. G. T., & Sidanius, J. (2008). We will hunt them down: How sdo and rwa fuel ethnic persecution of immigrants in fundamentally different ways. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 1455-1464.

Tovar Pinzón, H. (2001). Emigración y éxodo en la historia de Colombia. América Latina. Histoire & memoire. Retrieved from: https://www.alhim.revues.org/522

Varas-Diaz, N., & Serrano-García, I. (2003). The challenge of a positive self-image in a colonial context: A psychology of liberation for the Puerto Rican experience. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 103–115.

Verkuyten, M. (2005). Ethnic group identification and group evaluation among minority and majority groups: Testing the multiculturalism hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 121-138. Doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.121

Wolsko, C., Park, B., Judd, C. M., & Wittenbrink, B. (2000). Framing interethnic ideology: Effects of multicultural and color-blind perspectives on judgments of groups and individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 536-654. Doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.635

Zárate, M. A., & Shaw, M.P. (2010). The role of cultural inertia in reactions to immigration on the us/Mexico border. Journal of Social Issues, 66, 45-57. Doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01632.x

Zirkel, S. (2008). Creating more effective multiethnic schools. Social Issues and Policy Review, 2, 187-241.

Author notes

* Department of Psychology, Pace University; 41 Park Row, 13th Floor, Room 1317; New York, NY, USA 10038.

** Programa de Psicología, Universidad del Rosario; Carrera 24 #63C-69; Bogotá, Colombia

*** Department of Psychology, University of Macau; E21-3060 Humanities and Social Sciences Building, Avenida da Universidade;Taipa, Macau SAR.

**** Department of Psychology, Stony Brook University; Stony Brook, NY, USA 11794-2500.