Profiling Chilean Suicide Note-Writers through Content Analysis*

Perfil de suicidas chilenos vía análisis de contenido de notas póstumas

Perfil de suicidas chilenos que escreveram notas suicidas

Profiling Chilean Suicide Note-Writers through Content Analysis*

Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, vol. 34, no. 3, 2016

Universidad del Rosario

Received: September 13, 2015

Accepted: December 02, 2015

Abstract: Suicides account for 2000 deaths in Chile each year. With a suicide rate of 11.3, it is classified as a country with high suicide risk. Aims: to identify personality and cognitive characteristics of the group of Chilean suicides that left suicide notes, through a content analysis. Methods: descriptive field study with an ex post facto design. All suicides registered between 2010 and 2012 by the Investigations Police of Chile were analyzed, obtaining 203 suicide notes from 96 cases. The Darbonne categories for content analysis were used with the inter-judge method. Results: The mean age of the suicides was 44.2 (SD = 18.53). Most of the notes were addressed to family members (51.7%). The most expressed reasons were marital- or interpersonal-related (24.6%); another 23.6% expressed a lack of purpose or hopelessness (including depression, wish to die, low self-esteem). The most frequent content expressed were instructions (about money, children, and funeral). All of the notes showed logical thinking and were written with coherence and clarity. Notably 42% of the notes were marked by affections of fondness, love or dependence of others. Regarding attitudes, the most common were of escape or farewell (42.4%), followed by fatalism, hopelessness, frustration or tiredness (40%). 24 statistically significant differences were found throughout the categories of analysis, according to cohorts of age, marital status and sex. Conclusions: the findings contribute to the profiling of Chilean suicides and to the implementation of suicide prevention programs.

Keywords suicide notes, content analysis, suicide, Chile.

Resumen: En Chile anualmente mueren aproximadamente 2 000 personas por suicidio. La tasa de 11,3 suicidios lo ubica como país de alto riesgo. Objetivo: identificar características de personalidad y cognoscitivas del grupo de suicidas de Chile que dejaron nota suicida, realizando un análisis de su contenido. Método: estudio de campo, descriptivo y ex post facto. Se analizaron todos los casos de suicidio registrados del 2010 al 2012 por la Policía de Investigaciones de Chile, localizándose 203 notas de 96 suicidas. Se aplicó el método de interjueces y la guía de categorías de Darbonne para el análisis de contenido. Resultados: la edad promedio de los suicidas fue 44,2 años (SD = 18,53). La mayoría de las notas fueron dirigidas a familiares (51,7%). Las razones para el suicidio más comúnmente expresadas fueron maritales o interpersonales (24,6%); otro 23,6% expresó una falta de sentido para vivir (incluyendo desesperanza, depresión, deseos de morir y baja autoestima). El contenido más frecuente fueron instrucciones (sobre dinero, hijos o funeral). Todas las notas mostraron un curso de pensamiento lógico y fueron escritas con coherencia y claridad. Notablemente, 42% de las notas tenía afectos positivos, amor y dependencia de otros. En cuanto a actitudes, las más comunes fueron de escape o despedida (42,4%), seguidas por fatalismo, desesperanza, frustración y cansancio (40%). En las diferentes categorías de análisis (razones manifiestas para el suicidio, sentimientos, actitudes, afectos y enfoque general de la nota) se encontraron 24 diferencias significativas según cohortes de edad, estado civil y sexo. Conclusiones: los resultados coadyuvan para crear el perfil del suicida chileno y para la implementación de programas de prevención del suicidio.

Palabras clave: notas suicidas, análisis de contenido, suicidio, Chile.

Resumo: No Chile anualmente morrem aproximadamente 2000 pessoas por suicídio. A taxa de 11.3 suicídios o localiza como país de alto risco. Objetivo: identificar características de personalidade e cognoscitivas do grupo de suicidas do Chile que deixaram nota suicida, realizando uma análise de conteúdo das mesmas. Método: estudo de campo, descritivo e ex-post facto. Analisaram-se todos os casos de suicídio registrados de 2010 a 2012 pela Polícia de Investigações do Chile, localizando 203 notas de 96 suicidas. Aplicou-se o método de inter-juízes e a guia de Categorias de Darbonne para a análise de conteúdo. Resultados: a idade média dos suicidas foi 44.2 anos (SD = 18.53). A maioria das notas foram dirigidas a familiares (51.7%). As razões para o suicídio mais comumente expressadas foram maritais ou interpessoais (24.6%); outro 23.6% expressou uma falta de sentido para viver (incluindo desesperança, depressão, desejos de morrer e baixa autoestima). O conteúdo mais frequente foram instruções (sobre dinheiro, filhos ou funeral). Todas as notas mostraram um curso de pensamento lógico e foram escritas com coerência e claridade. Notavelmente, 42% das notas tinham efeitos positivos, amor e dependência de outros. Em quanto a atitudes, as mais comuns foram de escape ou despedida (42.4%), seguidas por fatalismo, desesperança, frustração e cansaço (40%). Nas diferentes categorias de análise (razões manifestas para o suicídio, sentimentos, atitudes, afetos e foco geral da nota) se encontraram 24 diferenças significativas segundo coortes de idade, estado civil e sexo. Conclusões: os resultados coadjuvam para criar o perfil do suicida chileno e para a implementação de programas de prevenção do suicídio.

Palavras-chave: notas suicidas, análise de conteúdo, suicídio, Chile.

Chile is a unitary presidential democratic republic located in the southwestern part of South America. With a population of 17.8 million, its population density is of 8.9/KM2 (National Institute of Statistics, 2014). According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP, 2012), Chile presents stable economic indicators and has reported increased levels of life satisfaction among the population; however this contrasts with citizen discomfort caused by limited access to opportunities and social rights (Salinas-Figueredo, 2014) and marked inequality in the distribution of wealth, education and health (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2013).

The crude death rate in Chile is of 5.7/1000 inhabitants; in the year 2012, 7.7% of the registered deaths were classified as violent, with a total of 1841 suicides and 687 homicides (National Institute of Statistics, 2014), numbers that indicate that homicides are low in comparison with the increase of suicides.

Suicide tendencies and characteristics present variations throughout the world and social groups. It is contrasting that only 24.5% of the suicides registered worldwide occur in high-income countries, whereas 75.5% of them occur in countries labeled as low- and middle-income (World Health Organization [WHO], 2014). In Latin America, 35 000 suicides are registered every year, with the highest rates corresponding to Guyana and Suriname (with rates above 15/100000 suicides, exceeding the global rate of 11.4), followed by Uruguay and Chile.

In Chile, around 2000 people die by suicide each year (Medical Legal Service, 2012), with a rate of 11.3/100000, 7 out of 8 suicides are committed by males (Bogado, Besa, Rabat, Reutter, & Carvajal, 2007). According to the OECD (2014), between 1990 and 2011, suicide rates in this country increased by 90%; a growth only exceeded by Korea among the 34 countries members of such organization. Furthermore, suicide patterns have changed in recent years, especially within age groups, as those 25-39 have reached the highest rates (Otzen, Sanhueza, Manterola, & Escamila-Cejudo, 2014). For Moyano and Barría (2006) the continuous increase in suicide rates in Chile is alarming, showing an irregular ascending curve correlated to economic factors such as the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) curve (r = 0.874). Previous Psychological Autopsy studies with Chilean suicides suggest the presence of psychiatric and psychological disorders in their samples (Gómez et al., 2014).

Suicide note analysis

Although risk factors and warning signs have been outlined extensively in previous research, Fowler (2012) has emphasized that there are no diagnostic tools to accurately predict suicide on an individual basis due to the complexity of the suicide phenomenon, characterized by a changing, fluid nature that is highly state-dependent. Assuming this, suicide notes have also been considered among the few elements in suicide research that help comprehend the psychological state of subjects in the moments before taking their lives. Having been written in the same context of the suicide act, they are a window to the suicidal mind (Shneidman, 1993). The study of suicide through content analysis applied to notes has been tested and widely verified as reliable (Leenars & Balance, 1981; Schwartz & Jacobs, 1984; Cerel, Moore, Brown, Van de Venne, & Brown, 2015).

It is known that notes are only left by a minority of suicides. Previous studies have estimated this proportion in a range between 10% and 43% of their cases (Pestian, Matykiewicz, & Linn-Gust, 2012; Chávez-Hernández, Páramo-Castillo, Leenaars, & Leenaars, 2006); it should be noted that a frequent research motive is to compare characteristics between suicides who left notes and those who did not, as psychological variations are implied (for example, Rogers, Bromley, McNally, & Lester, 2007).

Leaving a suicide note is not a random act, but a way to share thoughts and feelings to friends and family (Asif, 2012). The content of notes tends to include instructions to survivors and explanations about the motivations behind the suicide (Sanger & Veach, 2008; Freuchen & Groholt, 2013); and while expressions of affection have been prominently found in previous studies, these findings have been polarized, as both, mainly positive affections such as love, gratitude and admiration have been found (Sanger & Veach, 2008), but so have been negative affections, such as hopelessness, anger, fear and guilt (Pestian et al., 2012).

Personality traits have also been identified through content analysis of suicide notes, indicating that people who kill themselves tend to suffer from unbearable psychological pain, thought constriction, frustration, a need to escape and aggression towards one-self (Leenars, Girdhar, Dogra, Wenckstern, & Leenars, 2010; Zhang & Lester, 2008).

Suicide notes studies in Latin America

Suicide note studies are still scarce in Latin America; Among the first reported are those conducted in Mexico studying general population (Chávez-Hernández, 1988; Chávez-Hernández & Macías-García, 2007; Chávez-Hernández, Macías-García, & Luna-Lara, 2011) and one that focused on suicide notes left by children (Páramo-Castillo & Chávez-Hernández, 2007). Studies comparing Mexican and international samples have also been conducted (Chávez-Hernández et al., 2006; Chávez-Hernández, Leenaars, Chávez-de-Sánchez, & Leenaars, 2009).

In Argentina, Ruiz et al. (2003) studied a population of suicide-attempters aged 65 and over, comparing characteristics between those who had written a note and those who had not, finding that those who left notes had used methods of greater lethality and presented higher levels of hopelessness. In the same population, Matusevich (2003) found that the most frequent topics of the notes were related to physical illness, chronic pain, loneliness, depression, disability and isolation.

In Chile, Ceballos-Espinoza (2013, 2014) conducted a couple of studies; in the first one the author analyzed 170 notes from 80 suicide cases, comparing their socio-demographic data with the precipitant motivation and the suicide method, focusing on Erikson’s psychosocial stages of development; in the second one the author increased the sample size to explore the suicidal discourse in posthumous messages, concluding that suicide notes reflected ambivalence, tending to represent suicides as paradoxes about abandonment and emotional pain.

As previously stated, the alarming increase of suicides in Chile demands specialized research in order to implement effective prevention strategies that address the specific characteristics of a country that is markedly diverse in its communities, traditions, and geography. The aim of the present study was to identify personality traits and cognitive characteristics of the group of Chilean who wrote suicide notes through a content analysis.

Material and methods

This was a descriptive field study with an ex post facto design. The suicide notes were obtained from the archives of the Homicide Brigades of the Investigations Police of Chile, from all the registered cases of suicide in Chile between 2010 and 2012. 96 cases that had left at least one note were identified; with most of them having left more than one, a total of 203 notes were registered. The content analysis considered each one as an individual unit of analysis, with a simple blind control for the codifiers; that is to say, judges had no reference data of the deceased. It should be noted that due to the lack of an archive of suicide notes, it was necessary to completely review all the files of the cases legally labeled as suicides.

Ethical approval and institutional authorizations were obtained from the Investigations Police of Chile for the management and dissemination of the results, prior deletion of all information that could reveal the identity of the suicide cases, their relatives, or informants. The research protocol was authorized by the ethics committee of the Department of Research and Postgraduate Studies of University of Guanajuato.

The Darbonne (1969) list of categories for content analysis was used with the corresponding modifications for the Latin population suggested in previous studies (Chávez-Hernández, 1988; Chávez-Hernández et al., 2011). The Darbonne categories are: socio-demographic data, suicide method, addressee, reasons for the suicide expressed on the note, personality aspects (expressed feelings and attitudes), affect indicated, cognitive processes, specific content and a general focus of the note. It should be noted that the Darbonne categories were chosen as they reveal characteristics that allow interpretation and comprehension of psychodynamic aspects expressed in the suicide notes. This scheme has been translated, adapted, and modified for Latin- American populations (see studies referenced in the previous paragraph).

Data analysis procedure

Content analysis, as described by Berelson (1952, p. 18), is “a research technique for the objective, systematic, and quantitative description of the manifest content of communication”. In line with said procedure, each suicide note was accounted as a unit of analysis. The categories and variables were operationalized, and so were their codification. The judges were trained to score the absence or presence of each variable from the manifest content of each note to assure verifiability. The inter-judge method was employed; the team consisted of 3 post graduated clinical psychologists who obtained an agreement rate of 93.5% with a minimum expected of 85% for Social Sciences. The judges were trained for this study by an expert of content analysis. A first individual classification of each note was followed by a grouping for the final codification. The judges tested their classifications until a minimum of 90% of concordance was reached; the third judge interceded in case of discrepancies. The MAXQDA software for qualitative analysis was employed for the content analysis and to obtain scores for relative risk and significate differences between variables.

Results

Socio-demographic data and suicide method

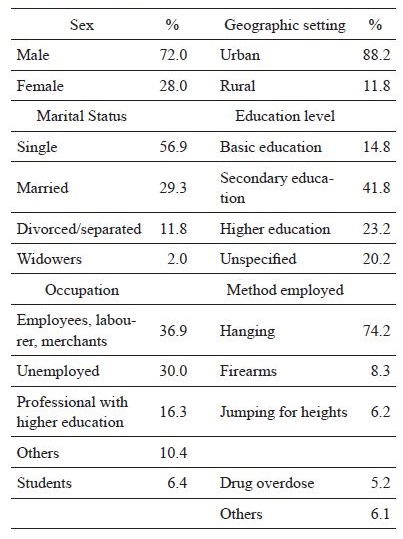

From the total sample, 37.5% of the subjects wrote more than one note, adding up to a total of 203 notes. The mean age of the suicides was 44.2 (SD = 18.53), the youngest one being a woman, 14, and the eldest a man, 91. Table 1 shows some socio-demographic data of the decedents.

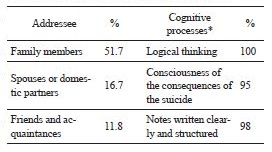

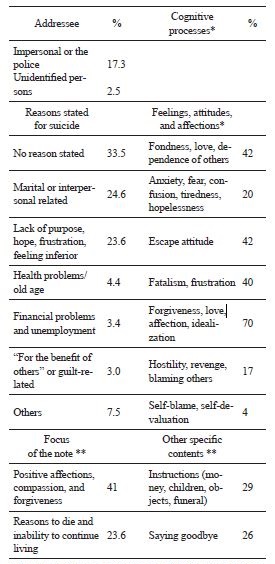

Addressee. Most of the notes were addressed to family members (51.7%), followed by those who were for spouses or domestic partners (16.7%), friends and acquaintances (11.8%) and those who were not addressed to a specific person, were impersonal, or addressed to the police (17.3%). 2.5% of the addressees were not possible to determine, as they were written to unidentifiable recipients.

Reasons stated. A third (33.5%) of the notes did not state any reason behind the suicide. However, the most expressed reasons were marital- or interpersonal- related, present in 24.6% of the sample. For example, the note from a woman, 22: “I regret the decision I have taken, I’m sorry, but I don’t think I can recover from losing this relationship, the most beautiful one I’ve had along with my baby”.

Another 23.6% expressed a lack of purpose or hopelessness (including depression, wish to die, low self-esteem, frustration and a feeling of inferiority). For example, a fragment from a man, 38: “They were always my motivation to fight and continue living, but without their love there are no more reasons to continue with this torture”.

Table 2 shows detail on these and other (less representative) reasons stated.

Other specific contents. The most frequent were instructions regarding money, children, objects, or their own funeral (29%), as appeared in a note by a woman, 22: “The only thing I ask is that you continue loving my baby. Take care of her, never leave her alone”.

Cognitive processes. All of the notes (100%) showed logical thinking, as their content was written with coherence. 95% of the notes showed consciousness of the consequences of the suicide act, suggesting an adequate contact with reality. It was also noticeable that 98% of the notes were written clearly and structured.

Feelings, attitudes and affections. Notably 42% of the notes were marked by affections of fondness, love or dependence of others (see table 2).

Regarding attitudes, the most common were of escape or farewell (42.4%), followed by fatalism, hopelessness, frustration or tiredness (40%), as seen in the following example by a woman, 37: “As much as I tried I couldn’t get over it, this new amorous deception has sunk me in sorrow. I know that I will never be happy with someone, even less if I could never be a mother”.

Feelings of forgiveness, love, affection and idealization were the most prevalent (70%) (see table 2). A lower percentage of the notes focused on self-devaluation, self-blame and self-punishment (4%). For example, the following fragment by a man, 41: “I love you very much, my sister. Forgive me for being such a bad brother. Perhaps God is punishing me, I don’t know. I have suffered enough, I’m tired and I want to rest. Forgive me for everything; I love you with all my heart.”

Statistically significant differences between variables

A second analysis consisted in the contrasting of three variables (sex, marital status, and age) with statistical techniques to prove hypotheses, using statistical tests such as Relative Risk, Chi-Squared, and Contingency Tables.

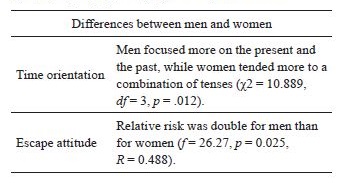

Table 3 shows both statistical differences found according to sex. While males expressed a time orientation focused on the present, females were more diverse as they tended to mixed time orientations. Additionally, males expressed more frequently an escape attitude in comparison to females.

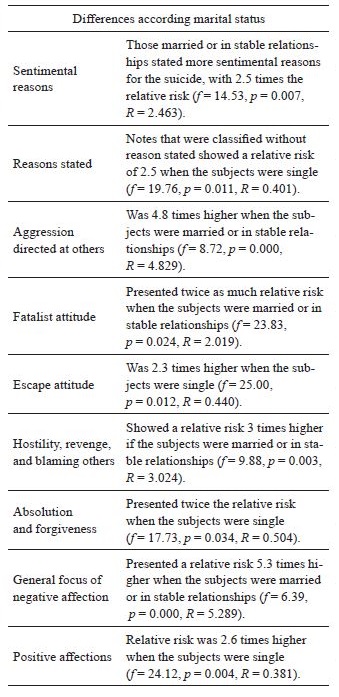

Table 4 shows nine statistically significant differences found regarding marital status. Those who were married or in stable relationships expressed twice the sentimental reasons for suicide than those who were single. In addition, singles tended more to omit a statement of reasons in their notes.

Notably, those married expressed more feelings of aggression (relative risk 4.8), a finding that coincides with a significant difference found in relation to affections of hostility, criticism, or revenge, which were more stated by those married (relative risk 3). On the other hand, singles tended more towards the expression of forgiveness, with twice the relative risk than those married. These results also concur with the more negative focus of the note found in notes written by married people (5.3 times the relative risk).

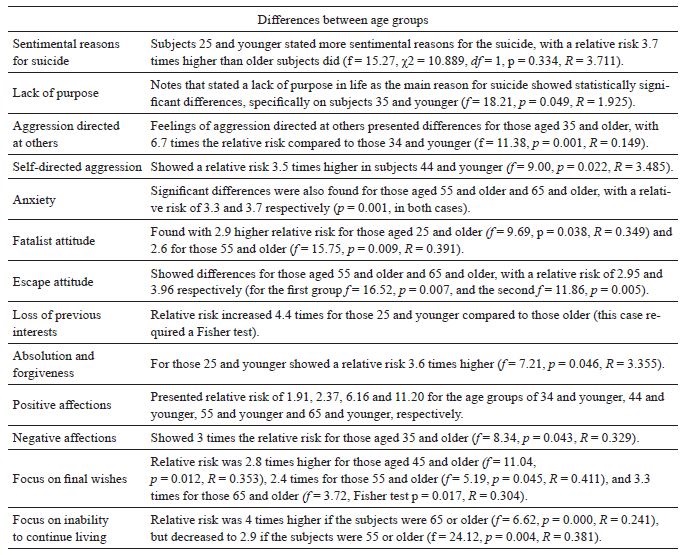

Lastly, table 5 shows 13 significant differences found between age groups. It should be noted that the age groups suggested by Darbonne were modified, as the studied sample was older. Specific parameters were set at 24, 34, 44, 54, and 64 or older.

Sentimental reasons for suicide were found three times as much in those aged below 25, in comparison to the rest of the sample. Feelings of aggression directed at others were notably present in those aged 35 and older, with a relative risk 6.7 times higher in comparison to those 34 and younger. Anxiety was found significantly increasing with age, as those 55-64 and 65 and older presented relative risks for it 3.3 and 3.7, respectively (p = 0.001 in both cases). A fatalist attitude was found with 2.9 higher relative risk for those aged 25 and older, followed by those aged 55 and older, with a relative risk of 2.6

Similarly, the relative risk for inability to continue living as the main reason expressed for suicide was found 4 times higher for those aged 65 and older.

On the other hand, a loss of previous interests was more significantly present in notes written by younger suicides, as those 25 and younger had 4.4 times the relative risk for this variable. This case required a statistical Fisher Test due to a minimum expected frequency of f = 1.77, making invalid the inferences from the Pearson Chi-Squared test.

Positive affections such as giving or soliciting forgiveness and compassion decreased inversely proportional to age; conversely, the relative risk for negative affections and hostility was found three times as much in those aged 35 and older.

Discussion

The social movements that have had place in Chile in the last century have contributed to the strengthening of an independent nation with educational and economic growth that promotes the use of research methodologies committed to reflect the reality of the nation’s specific vulnerable groups (Salinas-Figueredo, 2014).

Additionally, in recent years, the Ministry of Health of Chile (MINSAL, 2015) has piloted a national strategy for suicide prevention to reduce suicide behavior by 10%, especially among adolescents aged 10-19. This program is grounded on a system for epidemiological and clinical research of suicide; regional platforms for suicide prevention; clinical training for mental health professionals; and crisis intervention strategies (MINSAL, 2013). These national efforts reflect the aperture and concern from the corresponding authorities, which can also be drawn from the access given to review confidential files containing suicide notes for this research.

Two thirds (66.5%) of the studied notes included explanations behind the suicide, a proportion within the expected, as previous research (for example, Freuchen & Groholt, 2013) has found that such explanations were the main topic of suicide notes.

Regarding reasons stated for the suicide, the most prevalent in the studied sample were those referring to interpersonal, marital and family problems, found in 25% of all the notes, a rate also found by Sanger & Veach (2008). The second most common reasons found were those involving hopelessness, a lack of purpose, confusion and frustrated desires, a finding that concurs with previous research that found hopelessness as the primary stated reasons for suicide in notes (Pestian et al., 2012). It was also observed that the majority of the notes were addressed to family members, followed by those written to spouses, domestic partners, and friends, a finding that supports that both suicides and suicide notes tend to revolve around interpersonal themes.

The fact that most of the notes were focused on the expression of positive affections, alongside the expression of feelings such as love, appreciation and dependence of others, confirms the relevance of personal relationships in the determination for suicide. It should also be noted that these orientations and feelings, tending more to a positive nature, contrast with the lower presence of negative affections in the notes.

The evaluation of cognitive processes showed consistent data to support the hypotheses of suicide primarily as a rational, determined act, rather than spontaneous or impulsive. Logical and coherent course of thought was observed in all (100%) of the notes, while structured language was registered in 98% of them. Likewise, 95% of the notes showed consciousness of the consequences of the suicide act. These findings may be useful to highlight the importance of psychological and social aspects in suicide, as they support previous claims that killing oneself is not necessarily a consequence of psychotic disorders or severe mental disturbance (Freuchen & Groholt, 2013; Chávez-Hernández & Macías-García, 2007).

Through the analysis of differences in reasons stated, feelings, attitudes, affection and general focus of the notes, significances were drawn according to age group; these should be considered for future prevention and attention programs. The findings of this study suggest that the traditional and respectful place of care towards the elder has blurred from the social system. This particular age group consistently showed more traits of anxiety, escape, hostility, and aggression towards other family members, while positive affection decreased in the notes as age increased. On the other hand, the younger subjects of the sample showed a noticeable loss of previous interests and a lack of purpose and hope for living. This may be partially explained by the social characteristics of our time, in which planning for the future is continuously mined by limited access to opportunities and fierce competition in a high-demanding society.

Significant differences were also observed in the marital status analysis, most notably: those who were married more likely stated sentimental reasons for suicide, expressed more aggression directed at others, fatalist attitudes, hostile affections, revenge, hopelessness and a general negative focus of the note. These findings suggest that the marital institution, previously considered as the basic unity of the Chilean society, is going through a crisis. On the other hand, those subjects who were single were more prone to both, giving and soliciting forgiveness.

As a limitation of the present study, the sample only included those suicides who were registered as such by the Investigations Police of Chile and wrote suicide notes, excluding from the analysis those suicides who were not registered and those who did not leave any posthumous messages. Moreover, future studies should compare the findings of this study to international samples, from both Latin-American and across social contexts, to contribute to the drawing and profiling of Chilean suicides from similarities and differences, for a better implementation of effective suicide prevention and attention strategies.

References

Asif, A. (2012). Last thoughts of a sinking mind. Khyber Medical University Journal, 4(2), 69-70.

Berelson, B. (1952). Content analysis in comunication research. Glencoe: Free Press.

Bogado, M., Besa, C., Rabat, M. C., Reutter, P., & Carvajal, C. (2007). Desempleo y suicidio en Chile (1990-2001). Rev GPU, 3(2), 156-162.

Ceballos-Espinoza, F. (2014). El discurso suicida: Una aproximación al sentido y significado del suicidio basado en el análisis de notas suicidas [The suicidal discourse: an aproximation at the meaning of suicide based on the analysis of suicide notes]. Sciences PI Journal, 1(1), 53-66.

Ceballos-Espinoza, F. (2013). El suicidio en Chile: Una aproximación al perfil suicida a partir del análisis de notas suicidas [Suicide in Chile: an approximation at the profile of suicides from the analysis of suicide notes]. Estudios Policiales, 10(1), 77-92.

Cerel, J., Moore, M., Brown, M. M., van de Venne, J., & Brown, S. L. (2015). Who leaves suicide notes? A six-year population-based study. Suicide and Life-Threat Behavi, 45, 326-334. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12131

Chávez-Hernández, A. M. (1988). Análisis de contenido de las notas póstumas de los suicidados [Content analysis of suicide notes]. (Tesis Maestría en Psicología, Universidad Iberoamericana, México).

Chávez-Hernández, A. M., Leenaars, A. A., Chávez-de Sánchez, M., & Leenaars, L. (2009). Suicide notes from Mexico and the United States: A thematic analysis. Salud Pública De México, 51(4), 314-320.

Chávez-Hernández, A. M. & Macías-García, L.F. (2007). El fenómeno del suicidio en el Estado de Guanajuato [The suicide phenomenon in the state of Guanajuato]. México: Universidad de Guanajuato Ed.

Chávez-Hernández, A. M., Macías-García, L. F., & Luna-Lara, M. G. (2011). Notas suicidas mexicanas. Un análisis cualitativo [Mexican suicide notes: A quantitative analysis]. Pensamiento Psicológico, 9(17), 33-42.

Chávez-Hernández, A. M., Páramo-Castillo, D., Leenaars, A. A., & Leenaars, L. (2006). Suicide notes in Mexico: What do they tell us? Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 36(6), 709-715.

Darbonne, A. (1969). Suicide and age: A suicide note analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 33(1), 46-50.

Fowler, J. C. (2012). Suicide risk assessment in clinical practice: pragmatic guidelines for imperfect assessments. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 49(1), 81-90. doi: 10.1037/a0026148

Freuchen, A. & Groholt, B. (2013). Characteristics of suicide notes of children and young adolescents: An examination of the notes from suicide victims 15 years and younger. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 26(12), 1-13.

Gómez Ch, A., Opazo P, R., Levi A, R., Gómez Ch, M. S., Ibáñez H, C., & Nuñez M, C. (2014). Autopsias psicológicas de treinta suicidios en la IV Región de Chile. Rev. chil. neuro-psiquiatr, 52(1), 9-19.

Leenaars, A. & Balance, W. (1981). A predictive approach to the study of manifest content in suicide notes. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 37(1), 50-52.

Leenaars, A. A., Girdhar, S., Dogra, T. D., Wenckstern, S., & Leenaars, L. (2010). Suicide notes from India and the United States: A thematic comparison. Death Studies, 34(5), 426-440. doi: 10.1080/07481181003697712

Matusevich, D. (2003). Análisis cualitativos de ocho notas suicidas en la vejez [Qualitative analysis of 8 suicide notes in old age]. Vertex, 14, 141-145.

Medical Legal Service. (2012). Autopsias médico legales de fallecidos por lesiones auto infligidas intencionalmente según establecimiento médico legal periodo 2009-2011 [Medical Legal Autopsies of Deaths by Suicide 2009-2011]. Document 1022, August 22, 2013, Direction of SML.

Ministerio de Salud (MINSAL). (2013). Programa Nacional de Prevención del Suicidio. Retrieve from http://web.minsal.cl/sites/default/files/Programa_Nacional_Prevencion.pdf

Ministerio de Salud (MINSAL). (2015). Evaluación ex ante programas nuevos. Proceso formulación presupuestaria 2015. Programa Nacional de Prevención del Suicidio. Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Ministerio de Salud, Subsecretaría de Salud Pública. Retrieve from http://www.programassociales.cl/pdf/2014/PRG2014_1_59461.pdf

Moyano Díaz, E. & Barría, R. (2006). Suicidio y producto interno bruto (PIB) en Chile: hacia un modelo predictivo. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 38, 343-359.

National Institute of Statistics. (2014). Compendio estadístico 2014. Retrieved from http://www.ine.cl/canales/menu/publicaciones/calendario_de_publicaciones/pdf/compendio_2014.pdf

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2013). Economic Policy Reforms 2013: Going for Growth. OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/growth-2013

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2014). Suicides. In OECD, OECD Factbook 2014: Economic, Environmental and Social Statistics, OECD Publishing, Paris. doi: http://doi.org/10.1787/factbook-2014-99-en

Otzen, T. S., Sanhueza, A., Manterola, C., & Escamilla-Cejudo, J. A. (2014). Trends in suicide mortality in Chile from 1998 to 2011. Rev Med Chil, 142(3), 13.

Páramo-Castillo, D. & Chávez-Hernández, A. M. (2007). Maltrato y suicidio infantil en el Estado de Guanajuato [Abuse and child suicide in the State of Guanajuato]. Salud Mental, 30(3), 59-67.

Pestian, J. P., Matykiewicz, P., & Linn-Gust, M. (2012). What’s in a note: Construction of a suicide note corpus. Biomedical Informatics Insights, 5, 1-6. doi: 10.4137/BII.S10213

Rogers, J. R., Bromley, J. L., McNally, C. J., & Lester, D. (2007). Content analysis of suicide notes as a test of the motivational component of the existential- constructivist model of suicide. Journal of Counseling & Development, 85(2), 182-188.

Ruiz, M., Dabi, E., Vairo, M., Matusevich, D., Finkelsztein, C., & Faccioli, J. (2003). Notas suicidas en pacientes mayores de 65 años: Estudio comparativo (datos preliminares) [Suicide notes in patients 65 and older: A comparative study]. Vertex, 14, 134-140.

Salinas-Figueredo, D. (2014). Chile: obstáculos políticos de la democratización y malestar de la sociedad [Chile: political obstacles for democracy and civil discomfort]. Estudios Sociológicos, 32(94), 17-44.

Sanger, S. & Veach, P. (2008). The interpersonal nature of suicide: A qualitative investigation of suicide notes. Archives of Suicide Research, 12(4), 352-365. doi: 10.1080/13811110802325232

Schwartz, H. & Jacobs, J. (1984). Estudio fenomenológico de notas suicidas [Phenomenological Study of suicide notes]. In H. Schwartz (Ed.), Sociología Cualitativa (pp. 203-217). México: Trillas.

Shneidman, E. (1993). Suicide as psychache: A clinical approach to self-destructive behavior. Estados Unidos: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2012). Desarrollo humano en Chile 2012. Bienestar subjetivo: el desafío de repensar el desarrollo [Human development in Chile 2012. Subjective wellbeing: The challenge of rethinking development]. Retrieved from http://www.cl.undp.org/content/dam/chile/docs/desarrollohumano/

World Health Organization (WHO). (2014). Preventing suicide: A global imperative. Washington: OPS.

Zhang, J. & Lester, D. (2008). Psychological tensions found in suicide notes: a test for the strain theory of suicide. Archives of Suicide Research, 12(1), 67-73. doi: 10.1080/13811110701800962

Notes

* This study was partially funded by the 2013 institutional call for papers of the University of Guanajuato. The authors would like to thank the Investigations Police of Chile for allowing the access to the suicide notes.

Author notes

** Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to Ana-María Chávez-Hernández. Departamento de Psicología, Universidad de Guanajuato, Mexico. Email: anachavez@ugto.mx, anamachavez@hotmail.com

anachavez@ugto.mx

Additional information

Cómo

citar este artículo: Ceballos-Espinoza, F. & Chávez-Hernández, A. M.

(2016). Profiling Chilean suicide note-writers through content analysis. Avances en Psicología

Latinoamericana, 34(3), 517-528. doi: http://doi.org/10.12804/apl34.3.2016.06