Interventions to Reduce Stigma Toward People with Severe Mental Disorders in Ibero- America: A Systematic Review

Intervenciones para reducir el estigma hacia personas con trastornos mentales graves en Iberoamérica: una revisión sistemática

Intervenções para reduzir o estigma em relação às pessoas com transtornos mentais graves na América Latina: uma revisão sistemática

Contribution: Information gathering; Drafting and document preparation

Contribution: Information gathering; Drafting and document preparation

Contribution: Information gathering; Drafting and document preparation

Contribution: Information gathering; Drafting and document preparation

Contribution: Document review, corrections, adaptation and final approval

Contribution: Document review, corrections, adaptation and final approval

Contribution: Document review, corrections, adaptation and final approval

Contribution: Document review, corrections, adaptation and final approval

Interventions to Reduce Stigma Toward People with Severe Mental Disorders in Ibero- America: A Systematic Review

Revista Ciencias de la Salud, vol. 19, no. 1, 2021

Universidad del Rosario

Received: 18 february 2020

Accepted: 11 november 2020

Additional information

To cite this article: Vielma-Aguilera A, Castro-Alzate E, Saldivia Bórquez S, Grandón-Fernández P. Interventions to Reduce Stigma Toward People with Severe Mental Disorders in Ibero-America: A Systematic Review. Rev Cienc Salud. 2021;19(1):1-27. https://doi.org/10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/revsalud/a.10054

Abstract: Introduction: The main goal of the present review was to systematically compile data on interventions to reduce stigma in Ibero-America. Aim: To describe the characteristics and determine the main results of interventions required for reducing stigma toward people with severe mental disorders that have developed in the Latin America during 2007-2017. Materials and methods: A systematic review of articles from electronic databases such as Medline, ebscohost, Embase, lilacs, and SciELO, as well as gray literature from Google Scholar, published in English, Spanish, and Portuguese covering the period during January 2007 and December 2017 was performed. In order to evaluate the quality of the quantitative studies, the Robins criteria were used for quasi-experimental and experimental studies, and the caspe criteria were used for qualitative studies. Results: A total of 18 studies that met the inclusion criteria were selected; 75% of the studies were quantitative in nature, of which, one-quarter did not meet the quality criteria. Conclusions: Currently, there are only a few interventions established to reduce stigma in Ibero-America and they are mainly short-term. Our evaluation of the available literature facilitates the identification of the aspects that should be included in future research in order to reduce the possible biases that could arise when developing these types of studies.

Keywords: Social stigma, mental disorders, evaluation of results of therapeutic interventions.

Resumen: Introducción: el objetivo principal de la presente revisión fue compilar sistemáticamente datos sobre intervenciones para reducir el estigma en Iberoamérica. Objetivo: describir las características y determinar los principales resultados de las intervenciones para reducir el estigma hacia las personas con trastornos mentales graves que se han desarrollado en América Latina entre 2007 y 2017. Materiales y métodos: revisión sistemática de artículos de bases de datos electrónicas, como Medline, ebscohost, Embase, lilacs y SciELO, y literatura gris obtenida de Google Scholar, publicada en inglés, español y portugués que abarca el periodo comprendido entre enero de 2007 y diciembre de 2017. Para evaluar la calidad de los estudios cuantitativos, se utilizaron los criterios de Robins para los estudios cuasiexperimentales y experimentales, y los criterios caspe para los estudios cualitativos. Resultados: se seleccionaron 18 estudios que cumplieron con los criterios de inclusión; el 75% fueron cuantitativos, y de estos, una cuarta parte no cumplió con los criterios de calidad. Conclusiones: actualmente, existen pocas intervenciones para reducir el estigma en Iberoamérica y son principalmente a corto plazo. Nuestra evaluación de la literatura disponible ayuda a identificar aspectos que deberían incluirse en investigaciones futuras para reducir los posibles sesgos que podrían surgir al desarrollar este tipo de estudios.

Palabras clave: estigma social, trastornos mentales, evaluación de resultados de intervenciones terapéuticas.

Resumo: Introdução: o objetivo principal desta revisão foi compilar sistematicamente dados sobre intervenções para reduzir o estigma na América Latina. Objetivo: descrever as características e determinar os principais resultados das intervenções para redução do estigma em relação a pessoas com transtornos mentais graves que se desenvolveram na América Latina no período de 2007-2017. Materiais e métodos: realizou-se uma revisão sistemática de artigos de bases de dados eletrônicas como Medline, ebscohost, Embase, lilacs e SciELO, e literatura cinza obtida no Google Scholar, publicada em inglês, espanhol e português cobrindo o período de janeiro de 2007 e dezembro de 2017. Para avaliar a qualidade dos estudos quantitativos, foram utilizados os critérios de Robins para estudos quase experimentais e experimentais e os critérios caspe para estudos qualitativos. Resultados: foram selecionados um total de 18 estudos que atenderam aos critérios de inclusão; o 75% eram quantitativos e destes, um quarto não atendia aos critérios de qualidade. Conclusões: atualmente, existem poucas intervenções para reduzir o estigma na América Latina e são principalmente de curto prazo. Nossa avaliação da literatura disponível ajuda a identificar aspectos que devem ser incluídos em pesquisas futuras para reduzir os possíveis vieses que podem surgir no desenvolvimento deste tipo de estudos.

Palavras-chave: estigma social, transtornos mentais, avaliação de resultados de intervenções terapêuticas.

Introduction

Stigma is one of the main reasons why people with severe mental disorder (smd) avoid seeking professional help (1,2). This fact explains the gap in medical attention for these disorders, which vary between 32% of schizophrenia cases and 56% of depressive disorders (3). Some factors that contribute to this situation are the lack of knowledge and the presence of prejudice and discrimination, either real or anticipatory, toward people who suffer from these disorders (4,5,6). Furthermore, high-income countries have reported a prevalence of self-stigma >40%, while, in Latin America, a high prevalence of stigma has been reported in people with smd. Mascayano reported that public stigma was 40.5-70% (7); this proportion increased to 50-90% for self-stigma (8). Therefore, there is a need to implement interventions to reduce stigma within the general population as well as within the mental healthcare profession and for those who suffer from smd and their family members (9,10).

Considering the magnitude and impact of stigma, several strategies have been implemented for to reduce it over several decades (7,11,12). The three principal strategies include social protest, education, and contact. Social protest involves the uniting of people who share a specific diagnosis so as to demand changes in the situations that are harmful to them. Through this action, awareness can be raised about rejection and exclusion and individuals can advocate for their rights (10,13). Education is characterized by the distribution of information aimed at changing misperceptions, stereotypes, and discriminatory attitudes in various population groups (10,14). Finally, direct contact strategy usually involves a person with smd sharing their experience with professionals, students, and other people in order to favor the interaction between those affected and other social groups (10,15,16,17,18). However, the methods used to reduce stigma in mental health that are aimed at the general population are diverse and employ mass media mediums such as radio, newspapers, television, or internet (17,19,20). In interventions with specific groups, information is provided through workshops led by mental health professionals, and written documents and presentation of real cases are provided to help people understand the disorder (14,17,18). In situations where direct experience by the mental health service user cannot be accessed, indirect contact is employed through the analysis of cases, videos, vignettes, or interaction via social networks (18).

Unfortunately, studies on the effectiveness of interventions have revealed several discrepancies and gaps. For example, some studies have found that direct and indirect contact are equally effective (12,21,22), while others have reported that direct contact is better (17,23,24). Concerning the duration of the effect, a recent review by Thornicroft concluded that the results obtained were not sufficiently strong to determine the effect of long-term interventions, warranting further research on the subject (17). In addition, depending on the target population, the interventions have different objectives and strategies that make their comparison difficult (25). For instance, interventions are aimed at modifying the attitudes and knowledge based on educational programs among healthcare professionals (4,17,24), they are intended to reduce self-stigma for patients (4,17), and they are mainly provided through mass media for the general population (26). Furthermore, strategies based on coping have been proposed for families and caregivers to reduce stigma by association (8,27). On the other hand, interventions such as social contact and psychoeducation have been used in high school students to improve the level of awareness (22,29).

In low- and middle-income countries, the lack of resources and poor capacity to develop research are the factors that limit the implementation and follow-up of interventions to reduce stigma in mental health (24). There are only a few precedents to these types of interventions in Latin America, therefore, studies that serve as reference for cultural proximity and language mainly arise from Spain and Portugal (8). Moreover, there is a history of reforms in the healthcare systems between these two countries similar to that developed or under development in Latin America, which include guidelines such as reduction in the number of hospital beds and the incorporation of community services geared toward primary healthcare attention (30,31,32). Therefore, the gaps in research regarding the reduction of stigma among Latin America pose a challenge concerning identifying common areas of interventions. The investigators and policy makers need a solid empirical basis about the characteristics and impacts of stigma in order to assure that stigma can be handled and reduced (33). Based on the abovementioned reports, this review was conducted to describe the characteristics and the main results of interventions toward reducing stigma developed in Ibero-America during 2007-2017.

Materials and methods

A systematic review of articles from electronic databases such as Medline, ebscohost, Embase, lilacs, and SciELO and gray literature from Google Scholar between January 2007 and December 2017 was conducted. Based on the Virtual Health Library, the following Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS) were used: Social stigma or Attitude or Behavior or Prejudice or Discrimination or Social Distance or Social Perception, and Mental Disorder or Mood Disorder or Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder or Substance-Related Disorders or Mental Health and Interventions, Program or Health Literacy or Education or Health Promotion or Training or Cognitive Therapy or Narrative Therapy and Latin America and Spain and Portugal.

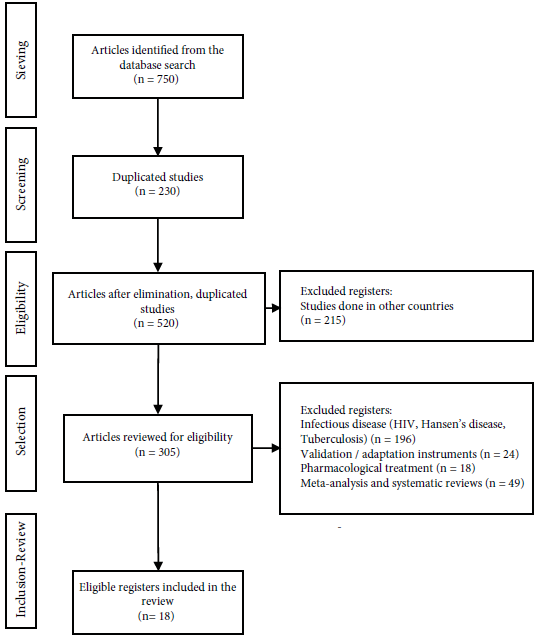

The inclusion criteria used were studies based on interventions to reduce stigma toward people with smd, quantitative and qualitative studies, and studies performed in individuals aged >14 years that evaluated changes in knowledge, attitudes, and/or behavior as a primary or secondary variable. Publications from Ibero-America were selected in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. The publications that were excluded included those on protocols related to randomized controlled trials, studies on validation and cultural adaptation of instruments for stigma assessment, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and studies related to common mental disorders and infectious diseases (Figure 1).

Two authors from the present study conducted independent searches and reviewed the abstracts for each publication in order to select those studies that met the inclusion criteria and discard those that met the exclusion criteria. In case of any discrepancies regarding adherence to the criteria between the authors, the opinion of a third expert evaluator was considered for arbitration.

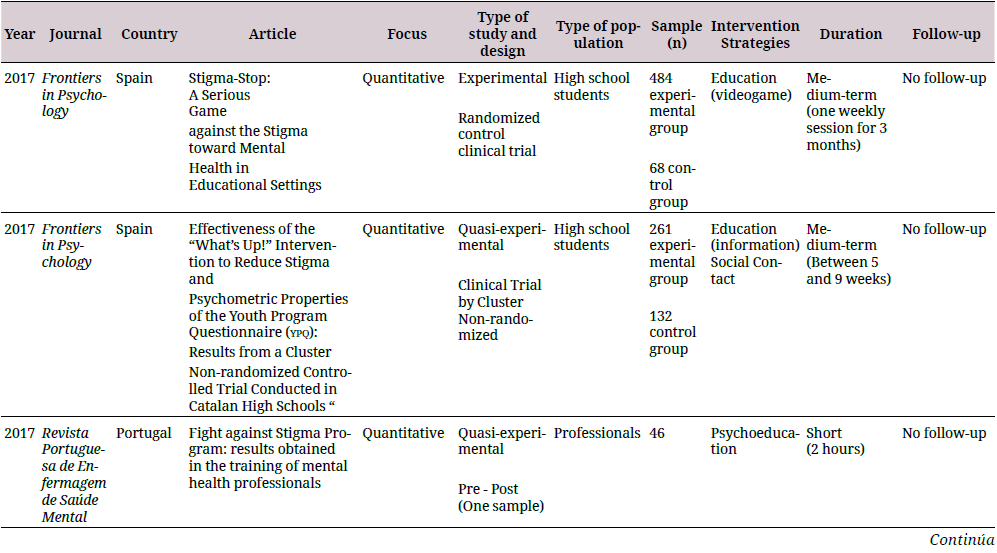

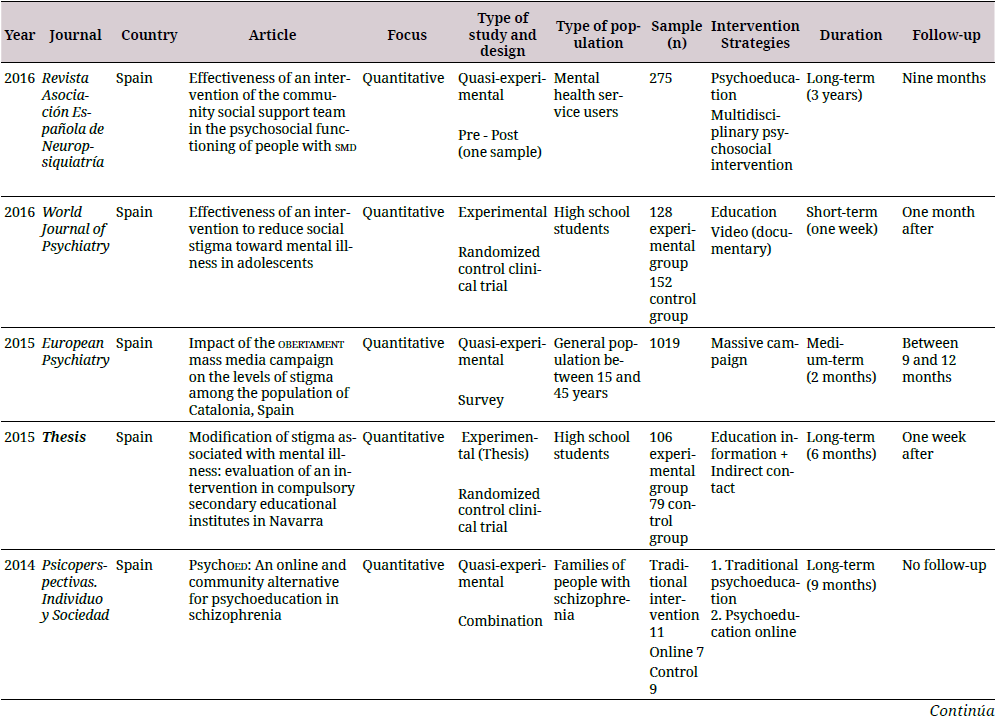

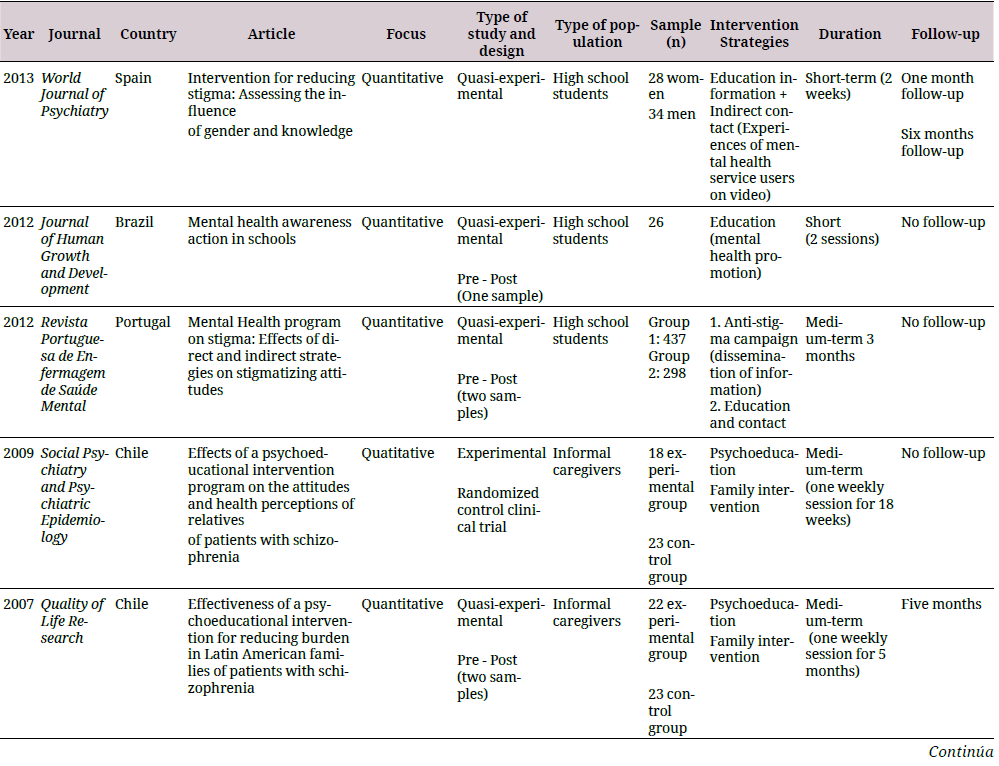

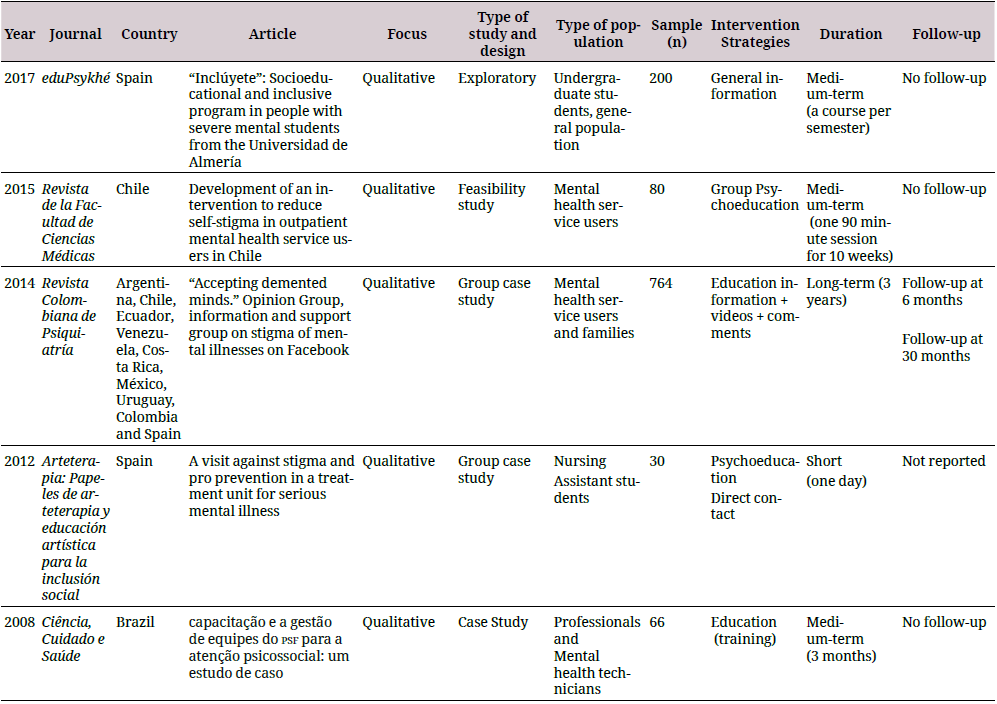

The information was arranged in a descriptive database developed in Excel® with the purpose of being evaluated and refined by the authors in case of duplicate results. A synthesis of the study was performed, which included the country in which the research was conducted, the approach used, the type of study, the type of population, the number of participants, the strategy and duration of the intervention, and follow-ups (if any). The results for the analysis of each category are shown in Table 1.

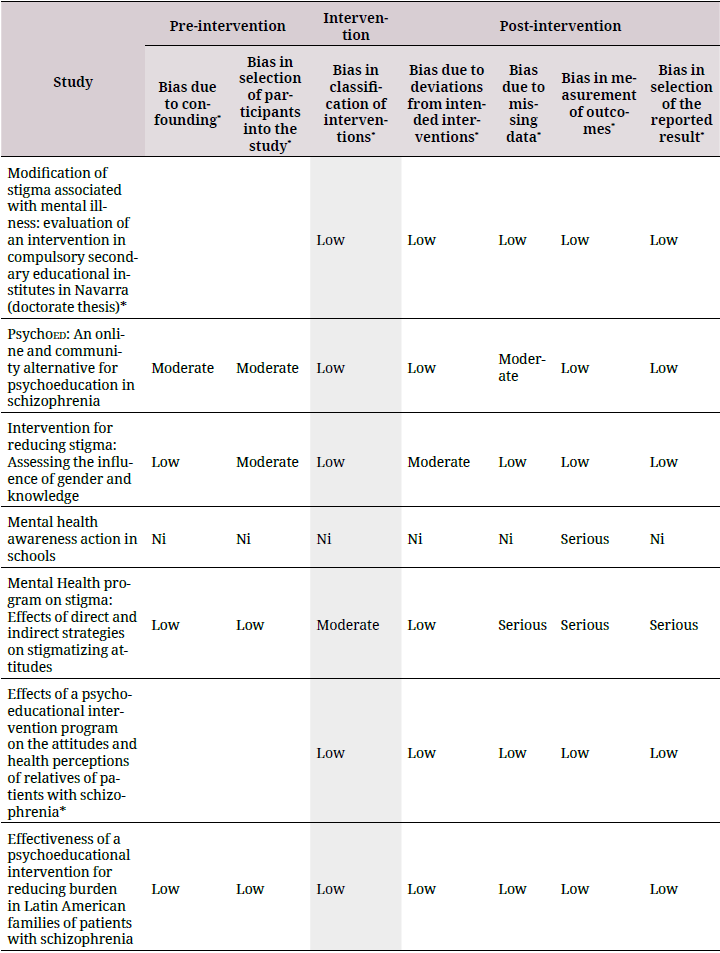

For the analysis of quantitative research, the Cochrane review methodology was employed for the experimental and quasi-experimental studies using the risk of bias tool 2.0 (robtool 2.0) (34) and the Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (Robins-I) tools (35). The assessment categories for both the tools corresponded to “low risk,” which refers to high-quality studies comparable to a controlled clinical trial; “moderate risk,” which refers to studies that offer solid evidence, but are not comparable to a controlled clinical trial; “serious risk,” which refers to studies that have some methodological problems; and “critical risk,” which refers to studies that have several problems and their results are not useful (34,35). These tools also provided an overall evaluation of the quality of the study and demonstrated that studies with a critical risk of bias should be excluded from a meta-analysis, warning about the limitations of studies with a serious risk of bias (35).

The parameters used in the evaluation of quasi-experimental studies were divided into three domains (35), as given below:

Pre-intervention:

Confounding variable: this refers to the effect of a variable on the intervention that needs to be examined with stratified or regression analysis.

Selection of participants based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Intervention:

Classification of interventions based on the definition of the program or strategy used.

Post-intervention:

Deviations in the treatment, which is related to changes produced in the participants as a result of contamination between the groups.

Incomplete data, which corresponds to the effect of data lost in the results after analyses.

Measurement of the outcome, which refers to the use of reliable tools to evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention.

Selection of the outcome, which is determined from the estimation of the effect of the intervention.

In the case of experimental studies, the criteria for confounding and selection of participants were not used because the randomization process minimizes the risk of bias (34). For this review, quantitative studies that met the quality criteria were characterized as having a description of a central hypothesis based on the effect of the intervention to reduce stigma, describing the intervention, presenting conclusions about the effect of the intervention, or being able to determine the effect from the data presented. In order to evaluate the quality of qualitative studies, the caspe methodology was used and the following criteria were considered (36): The presence of a clearly defined topic such as interventions to reduce stigma in any of its manifestations; relevance of the method used to answer the question of interest, description of the relationship with the objective of the research; and the usefulness of the results in a Ibero-America framework, considering the reproducibility of the study in different social and cultural contexts (37).

Results

The systematic search for information across the six databases yielded a total of 750 publications, of which 230 repeated studies were excluded. We eliminated 215 studies that were conducted in countries other than Ibero-America, thereby 305 studies met the eligibility conditions. We discarded 287 studies that did not involve interventions and mainly corresponded to studies related to stigma in infectious diseases such as hiv, Hansen’s Disease, or tuberculosis (n = 196), studies on scale validation and cultural adaptation (n = 24), pharmacological treatments (n = 18), and meta-analyses or systematic reviews (n = 49). Finally, a total of 18 studies were selected that met the inclusion criteria, including 10 from Spain (38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47), 2 from Portugal (48,49), 2 from Brazil (50,51), three from Chile (52,53,54), and one multicenter study coordinated from Colombia (55).

The types of studies that predominated were quantitative ones (n = 13), of which nine corresponded to quasi-experimental studies (38,39,40,44,48,49,50,51,54), and four to experimental studies (41,43,47,53). Out of the four studies with a qualitative approach, three corresponded to case studies using a group approach (56): The first one involved information strategies through the use of social networks (55), the second and the third used a direct contact strategy between the students and the mental health service users (45,46), and the fourth included the development of a training program for professionals (51). Finally, one study analyzed the reliability and safety conditions of an intervention to be used later in an experimental setup (52).

Out of all the studies reviewed, five fully complied with the quality characteristics that indicated a low probability of bias in the research (40,43,47,53,54). On the other hand, the principal source of bias in the quasi-experimental studies corresponded to the predominance of convenience samples, and the exclusion of randomization for the assignment of the control group when included. Previous studies have shown that gender can be a confounding variable for the results of interventions because women demonstrate a greater reduction in stigma (23). Accordingly, seven studies out of those reviewed considered this variable in their analyses (38,39,40,41,42,43,49). Table 2 summarizes the criteria for evaluating the quality of the studies.

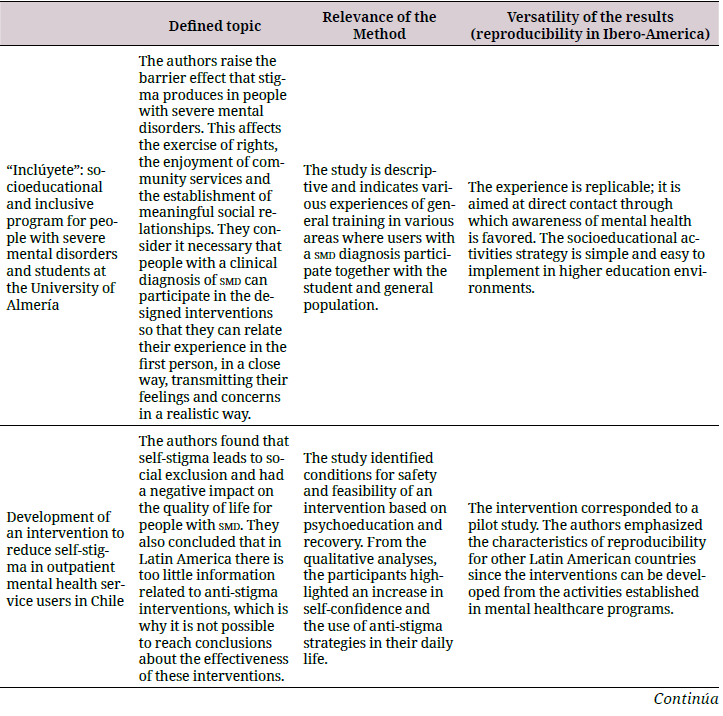

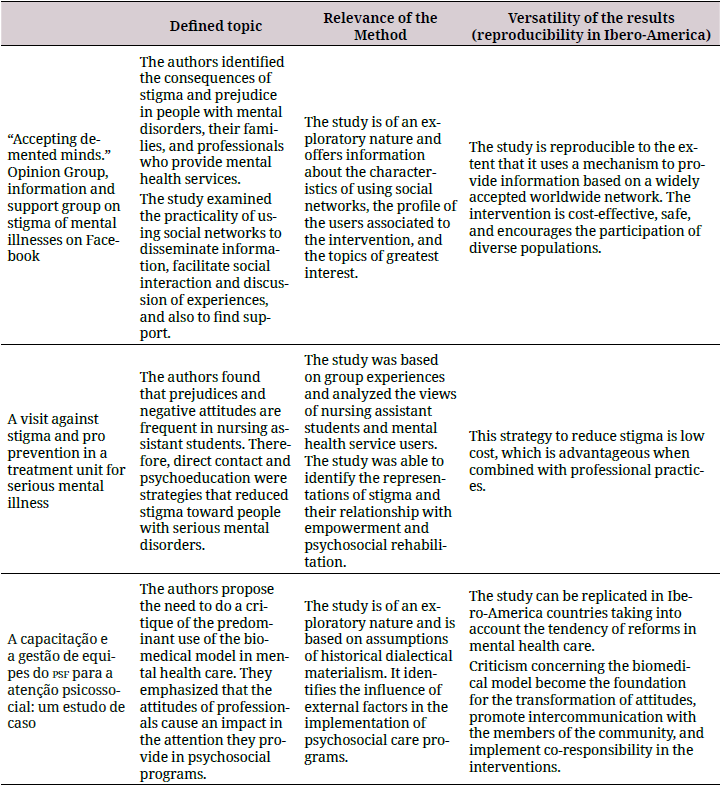

Regarding the qualitative publications, the studies clearly identified interventions to reduce stigma as the central theme with specific groups such as mental health service users (52,55), undergraduate students (45,46), and mental health professionals (51). All these studies determined the coherence between the method and the proposed objective by adopting an exploratory or descriptive approach. In addition, concerning the reproducibility criteria, these studies were feasible and relevant in the socio-cultural context to be repeated in IberoAmerica. Table 3 summarizes the quality characteristics of these studies.

The target population of the interventions corresponded mainly to high school students (n = 7), followed by family members and caregivers (n = 3), users of mental health services (n = 3), professionals (n = 2), general population (n = 1), mixed population–undergraduate students and general population (n = 1), and nursing assistant students (n = 1). The samples sizes were variable, for example, one of the experimental studies involved a total of 41 relatives (53), whereas the other two were conducted on a larger population of students (280 and 185 subjects) (41,43). Regarding the quasi-experimental studies, the sample size was size of 265-1019 (38, 39, 40, 49). The majority of the interventions of the reviewed studies were based on psychoeducation (n = 7) (39, 44, 47, 48, 52, 53, 54), education (n = 4) (41,50, 51,55), both education and contact (n = 5) (38,42,43,46,49), both psychoeducation and contact (n = 1) (45), and one was based on a massive campaign (n = 1) (40). All of the studies reported the duration of the intervention. Some were classified as short-term, which according to Yamaguchi are those that were conducted in a period of <1 month (23); 7 of the studies fit this description (41,42, 43,45,48,49,50). Other interventions were medium- and long-term, which according to Mehta are those conducted between 1 and 6 months and >6 months, respectively (57); 8 studies were medium-term (38,40,46,47,51,52,53,54), and three were long-term (39,44,55). A total of 11 studies were performed pre- and post-tests to determine the effect of the interventions (38,39,41,42,43,44,47,49,50,52,53), and only 33.3% of the studies reviewed reported some type of follow-up after the intervention (38,40,41,43,54,55).

The studies done with high school students demonstrated effectiveness and showed statistically significant differences between pre- and post-interventions. However, the effect size was small, and differences were noted according to the gender. The studies by AndrésRodríguez et al. and Martínez-Zambrano et al. concluded that, in women, stigma decreased more toward people with smd, and these results were related particularly to stigma subdomains such as authoritarianism and socially restrictive attitudes (38,42). Furthermore, de Simón-Alonso reported that women had more fear and less tendency to blame people with smd (43). Finally, the study performed by Cangas et al. reported that, in the experimental group, the preconceived idea of people with smd being dangerous was low (47).

Studies that involved family members and caregivers included measures of effect related to stigma by association. In this case, the feelings of shame and anger on the loss of social status due to the disorder were important reasons for the interventions. A study conducted by Gutiérrez-Maldonado et al. identified changes in affective attitudes (p = 0.006), cognition (p = 0.001), and behavior (p = 0.005), indicating that caregivers learned how to act, express their feelings, and think in a positive and flexible manner regarding the disorder (53,54). Soto-Pérez, on the other hand, studied the effect of an online intervention on the level of knowledge about schizophrenia in relatives of people with this diagnosis in Spain (44). Their results indicated that caregivers increased their knowledge about the causes of the disorder (p = 0.013), the treatments (p = 0.032), the family roles (p = 0.014), and the prodromes (p = 0.009). Furthermore, Cárdenas-Mancera et al. conducted an intervention using a social network site with a follow-up on the participation of mental health service users and family members on an online platform, but did not detect any direct measure of effect (55). They concluded that association to a network helps educate the population about diagnosis, treatment options, and psychosocial support mechanisms aimed at people with smd. However, the abovementioned two studies did not include information about how education affects the negative self-perception of the caregiver.

The majority of the studies that involved professionals and nursing assistant students were characterized by the use of qualitative methods; therefore, the effectiveness was evaluated from the perception of their experiences. For example, Oliveira et al. concluded that work training is a factor that favors the comprehensiveness of care and helps professionals promote autonomy of people with mental disorders. Their results indicated that, after a training process, attitudinal changes occurred in professionals that improved communication with mental health service users and their families (51). In addition, a study on awareness and direct contact performed in psychosocial rehabilitation programs in Spain identified attitudinal changes toward people with serious mental disorders in a group of nursing assistant students (45). The results demonstrated that the establishment of interaction strategies could modify attitudes and prejudices such as rejection and beliefs about danger and encouraged tolerance, expression of feelings, and recognition of individual capacities of people with smd. Barrantes et al., on the other hand, developed a quasi-experimental study in Portugal that involved a training program aimed at reducing preconceptions toward people with mental disorders, and they evaluated stigma as a dependent variable in the following nine domains: responsibility, grief, irritation, danger, fear, help, coercion, segregation, and avoidance (48). Their results demonstrated differences only in the avoidance domain, which revealed significant changes between the average baseline values and the average value obtained after the intervention (17.17 ± 5.42 vs 13.52 ± 5.37; t = 2.791; gl = 71; p = 0.007). However, they suggested that strategies to reduce stigma should be implemented in several areas such as educational institutions, workplaces, social health institutions, and even the media.

A study conducted in Spain by Ballesteros and Bertina evaluated a community intervention that involved multidisciplinary activities, intervention at home, and social support (39). The interest of the research group was focused on the impact of social and occupational functioning with the perception of stigma being a secondary variable that was determined from the decrease in feelings of low self-esteem and the deterioration of self-concept. They reported moderate effect sizes for the evaluated areas using the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (whodas ii), which incorporates questions concerning perception of other people’s attitudes toward people with smd in the domain of society participation. The study reported that mental health service users perceived a decrease in negative attitudes toward themselves after the intervention (the effect size was 0.31). Furthermore, these results remained constant after 3 years of association with the program, with a reported effect size of 0.32.

In Chile, Schilling et al. developed an intervention to reduce the impact of self-stigma on the users of outpatient healthcare centers (52). Preliminary results indicated that these users increased their self-confidence and used the strategies to reduce stigma. In addition, their data highlighted the importance of family participation, friends, the support of professionals, along with the search for help to reduce self-stigma. Moreover, the users valued intervention strategies that incorporated psychoeducation and a narrative approach. An intervention using social networks conducted by Cárdenas-Mancera et al. included users of mental health services from nine Ibero-America countries. Their results revealed that the formation of an opinion group promoted the development of discussion sessions that debated problems associated with mental disorders, including stigma. The study also reported that the topic that received the greatest number of interventions was stigma, which was acknowledged through 15 shared publications that talked about mental disorders, and that, on a monthly average, received comments or socialization of articles from at least two mental health service users (55).

Rubio-Varela et al. analyzed the impact of the obertament campaign in Catalonia (Spain), a study aimed at the general population using mass media such as television and internet. The results of the study indicated that 11% of the population spontaneously recalled the campaign, but only 0.8% remembered that it was related to stigma and discrimination toward people with mental health problems. Accordingly, the reported effect sizes were medium and low. For example, the effect size was low for the benevolence subscale, whereas medium effect sizes corresponded to maintaining a relationship with a friend who develops a mental disorder (d = 0.39) and living with someone with a mental disorder (d = 0.27) (40).

Discussion

This is one of the first reviews to systematically compile data on interventions to reduce stigma in Ibero-America. The main objectives of this review were to describe the characteristics and main results of interventions using quality assessment and a risk of bias profile for each study. We analyzed 18 studies conducted in Ibero-America aimed at reducing stigma toward serious mental disorder. Quantitative studies using mainly a quasi-experimental design (n = 9) predominated over qualitative studies (72.2% vs 27.8%). In the case of qualitative studies, three corresponded to group case studies, one study offered information on the feasibility and safety conditions of a pilot intervention of an experimental study, and another one described the development of a program to promote social inclusion of people with smd to avoid attitudinal barriers. It is therefore important to highlight the notorious lack of studies related to interventions to reduce stigma toward serious mental disorders in Ibero-America. Furthermore, an important gap was noted in the research conducted between high-income countries, mainly in English-speaking and Ibero-America countries (17,23).

Regarding the first objective and in relation to the level of quality determined by applying the Robins-I and robtools 2.0 tools, we noted that a quarter of the quantitative studies failed to satisfy the quality criteria. The main weaknesses recorded corresponded to the absence of information for the overall quality level of the studies, and, in studies that included this information, the quality levels showed a probability of serious or critical risk of bias, which would exclude them from any review process (34,35). However, due to the lack of research on the subject, we included all the studies in the present review to assess the quality so as to establish a baseline that will guide future researches (34,35). Notably, all studies with serious or critical risk of bias were conducted using a quasi-experimental design. The implementation of these studies has been widely developed in the field of social sciences because of their relevance; however, they have increased in the area of health due to their possible application in real life, unlike in experimental studies. The interest in using this type of research to summarize scientific data has increased because the external validity has improved with due consideration to the influence of variables that are difficult to isolate, such as the culture and motivation (58). Although the use of a quasi-experimental design may offer advantages in terms of implementation of the interventions, the results have limitations, especially when determining significant findings that lead to establishing possible causal relationships (58). Insufficient information on the quality of interventions to reduce stigma in Ibero-America reveals the need to develop new research that complements the data obtained until date; thus, being able to guide the decision-making step for public policy (59).

As for bias in the studies, the most frequent bias recorded was during the selection of participants. For example, the source of the sample was not reported in detail in one-third of the quasi-experimental studies (39,42,44). However, previous studies indicated that this type of a bias is common, necessitating the consideration of planning an intervention based on this design (60). It should be mentioned that there was a heterogeneity of interventions in terms of content and strategies and their applications, duration, and evaluation of the results and follow-ups; these last two aspects were related to the presence of bias post-intervention. Moreover, in two-thirds of the reviewed studies, serious biases were noted in the outcome measurements because of insufficient information to estimate the effectiveness of the intervention (48-50). A recurrent problem was noted since it was indicated in a previous review (23). There were only two quasi-experimental studies that reported sufficient information to classify them as low risk of bias for the three dimensions of pre-intervention, intervention, and post-intervention (40,54).

More importantly, the studies focused on relevant populations, for example, students, family or informal caregivers, the general population, mental health service users, and professionals, which is in agreement with the majority of researches that focuses on high school and university students followed by mental health service users, family members, and professionals (17,61,62). Unlike researches conducted in other countries, the low number of studies conducted in Ibero-America with the general population remains notable (17). The reason for this is most likely related to the fact that mass campaigns are expensive and require institutional support. Unfortunately, these conditions are not always present in Latin American countries since the resources allocated to mental health are usually low (63).

Concerning the samples in the studies we reviewed, they were mainly for convenience, and the largest sizes were in studies with students, similar to that in other countries (8,41,43,57). Meanwhile, the sample sizes for intervention with mental health service users and family members were reduced, perhaps due to the restrictions related to ethical criteria, access to health services, and/or motivation of the participants (8,10). Therefore, these results demonstrate the need to concentrate efforts on the design of protocols with larger and more representative samples (34,35). Hence, it is important to carefully consider the ethical guidelines established in each country when developing the recruitment process (64).

In the present review, we identified seven short-term, eight medium-term, and three longterm interventions; however, the duration of the intervention was not related to its effectiveness. These results coincide with those presented in a review by Yamaguchi et al. that demonstrated that interventions with different durations can have similar effects (23). On the other hand, Mehta et al. indicated that the data on the effectiveness of interventions is precarious since the results are only favorable for short-term durations, which necessitates follow-up studies to establish the effectiveness of long-term interventions (57).

Concerning the second objective, the heterogeneity of the implementations for the interventions makes it difficult to evaluate their impact. In the present review, the majority of the interventions that used a combination of education and contact strategies were effective, albeit with a low effect size (17,61). Out of the different intervention techniques applied, direct and indirect social contact demonstrated better results when compared with interventions such as education (23,65). Hence, interaction with people with a mental disorder has been documented as a strategy that produces changes in attitudes and social distance (61). However, Gronholm et al., Yanos et al., and Gerlinger et al. indicated that this type of strategy could increase its effect when combined with some type of an education approach (61,62,66). Indeed, the use of strategies involving multiple mechanisms of social contact have been suggested for results, such as recovery (67).

Here, we identified medium (d = 0.42) and high (d = 0.82 and 0.85) effect sizes in three studies that implemented the psychoeducational strategies. However, these studies were characterized by having small sample sizes (44,53,54). Thus, Mehta et al. concluded that the effect size varies between a medium effect for an increase in knowledge (d = 0.54) and a low effect for a decrease in stigmatizing attitudes (d = 0.22) (57). In case of studies included in the present review, the results were not sufficiently detailed to determine the extent of the effect of the interventions. In some cases, there was insufficient data presented, which made it difficult to reach a conclusion in favor of any specific strategy. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that efforts are being made in Ibero-America to reduce stigma toward people with smd. However, there are only substantial differences related to the development and impact of interventions between Spain, Portugal, and Latin America, which seems to be related to the health aspects of these countries. In Ibero-America, a process of psychiatric reform was performed, which included the concern and fight against stigma in different manners. In Spain, for example, there are campaigns aimed at the general population that are constantly working to raise awareness about stigma and ways to reduce it (18,40). Similarly, of the studies reviewed, quantitative studies predominated, in which 2 randomized controlled trials stood out along with a quasi-experimental study with a low probability of bias (40,41,43). Portugal has very similar characteristics to Spain in terms of the psychiatric reform processes, but there was less evidence found on issues related to stigma reduction in mental health in the former (31). In Latin America, the process is disparate; however, it is important to highlight the advances that are being made to reduce stigma in some countries in the area. In the case of Chile, for example, the approach to this topic was defined as a priority in the Mental Health Strategic Plan. It was declared that “by the year 2020, at least 50% of the healthcare services must implement a plan of dissemination and support for the exercise of rights and anti-stigma” (68). This plan involves the incorporation of a transversal anti-stigma vision as a public policy guideline in mental health that responds to the needs of the population with smd and their families, similar to that in Argentina, Brazil, and Colombia (24,69,70,71). However, it is necessary to reinforce these advances to reduce the current gap in the medical care and treatment of people with smd. Accordingly, one of the most relevant ways is to collect reliable information in order to evaluate, compare, and replicate successful experiences that are well adapted to the cultural and social conditions of each country and which improves the quality of life for users of mental health services and their families (8,14,52).

This review is a first step toward the systematization and quality assessment of research in stigma reduction in Ibero-America. Our analyses facilitate the recognition of those aspects that should be incorporated in the future studies in order to reduce possible biases. In addition, the information presented here is expected to be useful toward establishing a baseline to help determine the influence of contextual factors in the occurrence of stigma in diverse populations. Furthermore, an aspect to consider for both future reviews and programs toward reducing stigma corresponds to the need for the development of operational definitions for the duration of the intervention. In the present review, we identified a predominance of medium-term interventions (44%). However, for new protocols, it is crucial to implement mechanisms that identify the differences between the duration time and the follow-up time, with these elements being assumed as independent parameters that would expedite the organization of activities, final results, and effectiveness of the intervention (17,57).

The present review reveals limitations that prompt caution when it comes to interpreting the results while highlighting insufficient information regarding interventions to reduce stigma in Ibero-America and the heterogeneity of the populations at which they are directed as well as the strategies and mechanisms employed. Unfortunately, this lack of information complicates the development of methodological approaches to measure the global effect.

Authors’ contribution

Alexis Vielma-Aguilera and Elvis Castro-Alzate: Information gathering, drafting and document preparation.

Sandra Saldivia Bórquez and Pamela Grandón-Fernández: Document review, corrections, adaptation and final approval.

Conflict of interests

None declared.

References

1. Ross CA, Goldner EM. Stigma, negative attitudes and discrimination towards mental illness within the nursing profession: a review of the literature. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2009;16(6):558–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01399.x

2. Fox AB, Smith BN, Vogt D. How and when does mental illness stigma impact treatment seeking? Longitudinal examination of relationships between anticipated and internalized stigma, symptom severity, and mental health service use. Psychiatry Res. 2018;268:15–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.036

3. Thornicroft G. Most people with mental illness are not treated. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):807– 08. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61392-0.

4. Henderson C, Evans-Lacko S, Thornicroft G. Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):777–80. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301056

5. Dalky HF. Mental illness stigma reduction interventions: review of intervention trials. West J Nurs Res. 2012;34(4):520–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945911400638

6. Dua T, Barbui C, Clark N, Fleischmann A, Poznyak V, van Ommeren M, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in low- and middle-income countries: summary of WHO recommendations. PLoS Med. 2011;8(11):e1001122. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001122

7. Stuart H, Arboleda-Flórez J, Sartorius N. Paradigms lost: fighting stigma and the lessons learned. Oxford, New York. 2012.

8. Mascayano F, Tapia T, Schilling S, Alvarado R, Tapia E, Lips W, et al. Stigma toward mental illness in Latin America and the Caribbean: a systematic review. Rev Bras psiquiatr. (9). 2016;38(1):73–85. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2015-1652

9. Yang L, Kleinman A, Link B, Phelan J, Lee S, Good B. Cultura y estigma: la experiencia moral. Este País. 2007;195:4–15.

10. Mascayano-Tapia F, Lips-Castro W, Mena-Poblete C, Manchego-Soza C. Estigma hacia los trastornos mentales: características e intervenciones. Salud Ment. 2015;38:53–8.

11. Rao D, Elshafei A, Nguyen M, Hatzenbuehler ML, Frey S, Go VF. A systematic review of multi-level stigma interventions: state of the science and future directions. BMC Med. 2019(41);17(1):41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1244-y

12. Nguyen E, Chen TF, O’Reilly CL. Evaluating the impact of direct and indirect contact on the mental health stigma of pharmacy students. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(7):1087–1098. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-011-0413-5

13. Corrigan PW, O’Shaughnessy JR. Changing mental illness stigma as it exists in the real world. Aust Psychol. 2007;42(2):90–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050060701280573

14. Mascayano F, Schiling S, Escobar E, Abeldaño R, Gallo V. Programas para reducir estigma hacia la enfermedad mental: lecciones para Latinoamérica; 2015.

15. Allport G. Nature of prejudice. Oxford, England: Addison-Wesley; 1954.

16. Corrigan P, Markowitz FE, Watson A, Rowan D, Kubiak MA. An attribution model of public discrimination towards persons with mental illness. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44(2):162– 79. https://doi.org/10.2307/1519806

17. Thornicroft G, Mehta N, Clement S, Evans-Lacko S, Doherty M, Rose D, et al. Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. Lancet. 2016;387(10023):1123–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00298-6

18. López M, Laviana M, Férnandez L, López A, Rodríguez AM, Aparicio A. La Lucha contra el estigma y la discriminación en salud mental. Una estrategia compleja basada en la información disponible. Rev Asoc Esp Neuropsiq. 2008;28(11):43–83. https://doi.org/10.4321/S0211-57352008000100004

19. Cazzaniga-Pesenti J, Suso-Araico A. Salud mental e inclusión social. Situación actual y recomendaciones contra el estigma. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad; 2015.

20. Maiorano A, Lasalvia A, Sampogna G, Pocai B, Ruggeri M, Henderson C. Reducing stigma in media professional: is there room for improvement? Results from a systematic review. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(10):702–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743717711172

21. Wood AL, Wahl OF. Evaluating the effectiveness of a consumer-provided mental health recovery education presentation. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2006;30(1):46–53. https://doi.org/10.2975/30.2006.46.53

22. Yamaguchi S, Mino Y, Uddin S. Strategies and future attempts to reduce stigmatization and increase awareness of mental health problems among young people: a narrative review of educational interventions. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65(5):405–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02239.x

23. Yamaguchi S, Wu SI, Biswas M, Yate M, Aoki Y, Barley EA, et al. Effects of short-term interventions to reduce mental health related stigma in university or college students. A systematic review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201:490Y503;201(6):490–503. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e31829480df

24. Stuart H. Reducing the stigma of mental illness. Glob Ment Health. 2016;3:(e17):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2016.11

25. Henderson C, Gronholm PC. Mental health related stigma as a “wicked problem’: the need to address stigma and consider the consequences. Int J Environ Heal R. 2018;15(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061158

26. Michaels PJ, Corrigan PW, Buchholz B, Brown J, Arthur T, Netter C, et al. Changing stigma Through a consumer-based stigma reduction program. Commun Ment Health J. 2014;50(4):395–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-013-9628-0

27. Mak WWS, Cheung RYM. Affiliate stigma among caregivers of people with intellectual disability or mental illness. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2008;21(6):532–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2008.00426.x

28. Alcalá-Pompeo D, de Carvalho A, Morgado-Olive A, Graça Girade-Souza M, Frari-Galera S. Estrategias de enfrentamiento de familiares de pacientes con trastornos mentales. Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem. 2016;24:(e2799):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1590/1518- 8345.1311.2799

29. Mellor C. School-based interventions targeting stigma of mental illness: systematic review. Psychiatr Bull. 2014;38(4):164–71. https://doi.org/10.1192/pb.bp.112.041723

30. Saavedra-Macias F. Cómo encontrar un lugar en el mundo: explorando experiencias de recuperación de personas con trastornos mentales graves. Hist Cienc Saude Manguinhos. 2011;18(1):121–39. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-59702011000100008

31. Almeida-Filho A, da Silveira-Fortes F, Pina-Queirós P, de Almeida-Peres M, dos Santos Vidinha T, Alves-Rodrigues M. Trajetória histórica da reforma psiquiátrica em Portugal e no Brasil. Rev Enferm Ref. 2015;4(4);Série:117–25. https://doi.org/10.12707/RIV14074

32. Minoletti A, Sepúlveda R, Horvitz-Lennon M. Twenty years of Mental Health Policies in Chile: lessons and challenges. Int J Ment Health. 2012;41(1):21–37. https://doi.org/10.2753/IMH0020-7411410102

33. Gaebel W, Zäske H, Baumann AE. The relationship between mental illness severity and stigma. Acta psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2006;(49)429(429):41–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00716.x

34. National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. Appraising the risk of bias in randomized trials using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool 2017. (Available from: http://www.nccmt.ca/resources/search/280

35. Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:(i4919):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919

36. Cabello J. Plantilla para ayudarte a entender una Revisión Sistemática. En: CASPe. Guías CASPe de Lectura Crít de la Lit Med. Alicante: Caspe, Cuaderno. 2005;I.

37. Oliva P, Buhring K. Investigación cualitativa y evidencia en salud: respuestas fundamentales para su comprensión. Rev Chil Salud Publ. 2011;15(3):173–79. https://doi.org/10.5354/0717-3652.2011.17714

38. Andrés-Rodríguez L, Pérez-Aranda A, Feliu-Soler A, Rubio-Valera M, Aznar-Lou I, Serrano-Blanco A, et al. Effectiveness of the “what’s up!” intervention to reduce stigma and psychometric properties of the Youth Program Questionnaire (YPQ): results from a Cluster non-randomized controlled trial conducted in Catalan high schools. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1608. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01608

39. Ballesteros F, Bertina A. Efectividad de la intervención del Equipo de Apoyo Social Comunitario en el funcionamiento psicosocial de personas con trastorno mental grave. Rev Asoc Esp Neuropsiq. 2016;36(130):299–323. https://doi.org/10.4321/S0211-57352016000200002

40. Rubio-Valera M, Fernández A, Evans-Lacko S, Luciano JV, Thornicroft G, Aznar-Lou I, et al. Impact of the mass media obertament campaign on the levels of stigma among the population of Catalonia, Spain. Eur Psychiatry. 2016;31:44–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.10.005

41. Vila-Badia R, Martínez-Zambrano F, Arenas O, Casas-Anguera E, García-Morales E, Villellas R, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention for reducing social stigma towards mental illness in adolescents. World J Psychiatr. 2016;6(2):239–47. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v6.i2.239

42. Martínez-Zambrano F, García-Morales E, García-Franco M, Miguel J, Villellas R, Pascual G, et al. Intervention for reducing stigma: assessing the influence of gender and knowledge. World J Psychiatr. 2013;3(2):18–24. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v3.i2.18

43. de Simón Alonso L. Modificación del estigma asociado a la enfermedad mental: evaluación de una intervención en institutos de enseñanza secundaria obligatoria en Navarra. Madrid: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid; 2015.

44. Soto-Pérez F, Franco-Martín M. PsicoED: una alternativa online y comunitaria para la psicoeducación en esquizofrenia. Psicoperspectivas. 2014;13(3):118–29. https://doi.org/10.5027/psicoperspectivas-Vol13-Issue3-fulltext-416

45. Castillo Lasala M, Orna Díaz L, Pérez Rojo JA. Una visita contra el estigma y por la prevención en un centro de tratamiento para trastorno mental grave. Arteterapia. 2012;7:281–294. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_ARTE.2012.v7.40775

46. Cangas A, López A, Orta A, Gallego J, Alias I, Soriano C, et al. Inclúyete: Programa Socioeducativo e Inclusivo para Personas con Trastorno Mental Grave y Estudiantes en la Universidad de Almería. Edupsykhé. 2017;16(1):86–97

47. Cangas AJ, Navarro N, Parra JMA, Ojeda JJ, Cangas D, Piedra JA, et al. Stigma-stop: A serious game against the stigma toward mental health in educational settings. Front Psychol. 2017;8:1385. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01385

48. Barrantes FR, Violante C, Graça L, Amorim I. Programa de Luta contra o estigma: resultados obtidos na formação nos pro!ssionais de saúde mental. Rev Port Enferm Saúde Ment. 2017;Spe;5(spe5):19–24. https://doi.org/10.19131/rpesm.0162

49. Oliveira S, Carolino L, Paiva A. Programa Saúde mental sem estigma: efeitos de estratégias diretas e indiretas nas atitudes estigmatizantes. RPESM. 2012;8(8):30-37. https://doi.org/10.19131/rpesm.0068

50. Campos L, Palha F, Dias P, Sousa-Lima V, Veiga E, Costa N, et al. Mental health awareness intervention in schools. J Hum Growth Dev. 2012;22(1):259–66

51. Oliveira AGB, Conciani ME, Marcon SR. A capacitação E a gestão de equipes do psf PARA a atenção psicossocial: um estudo de caso. Cienc Cuid Saude. 2008;7(3):376–84. https://doi.org/10.4025/cienccuidsaude.v7i3.6511

52. Schilling S, Bustamante JA, Sala A, Acevedo C, Tapia E, Alvarado R, et al. Development of an intervention to reduce self-stigma in outpatient mental health service users in Chile. Rev Fac Cienc Med (Cordoba, Argentina). 2015;72(4):284–94.

53. Gutiérrez-Maldonado J, Caqueo-Urízar A, Ferrer-García M. Effects of a psychoeducational intervention program on the attitudes and health perceptions of relatives of patients with schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44(5):343–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0451-9

54. Gutiérrez-Maldonado J, Caqueo-Urízar A. Effectiveness of a psycho-educational intervention for reducing burden in Latin American families of patients with schizophrenia. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(5):739–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-007-9173-9

55. Cárdenas-Mancera K, De Santacruz C, Salamanca M. Aceptando mentes dementes. Grupo de opinión, información y apoyo sobre el estigma de las enfermedades mentales en Facebook. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2014;43(3):139–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcp.2014.02.007

56. Onwuegbuzie A, Leech N. Sampling designs in qualitative research: making the sampling process more public. Qual Rep. 2007;12(2):238–54.

57. Mehta N, Clement S, Marcus E, Stona AC, Bezborodovs N, Evans-Lacko S, et al. Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental health-related stigma and discrimination in the medium and long term: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(5):377–84. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.151944

58. Bärnighausen T, Tugwell P, Røttingen J, Shemilt I, Rockers P, Geldsetzer P, et al. Quasiexperimental study designs series. – Paper 4: uses and value. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.02.017

59. Henderson C, Noblett J, Parke H, Clement S, Caffrey A, Gale-Grant O, et al. Mental health-related stigma in health care and mental health-care settings. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(6):467–82. https://doi.org/(14)10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00023-6

60. Manterola C, Otzen T. Estudios experimentales 2 parte: estudios cuasi-experimentales. Int J Morphol. 2015;33(1):382–87. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-95022015000100060

61. Gronholm PC, Henderson C, Deb T, Thornicroft G. Interventions to reduce discrimination and stigma: the state of the art. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(3):249–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1341-9

62. Yanos PT, Lucksted A, Drapalski AL, Roe D, Lysaker P. Interventions targeting mental health self-stigma: a review and comparison. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2015;38(2):171–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000100

63. Mascayano-Tapia F, Armijo J, Yang L. Addressing stigma relating to mental illness in lowand middle-income countries. Front Psychiatry. 2015;6(38):1–4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00038

64. Yepes-Delgado C, Ocampo-Montoya A. Comités de ética y salud mental. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2017:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcp.2017.05.011

65. Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JD, Rüsch N. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr Serv (Washington, DC). 2012;63(10):963–73. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100529

66. Gerlinger G, Hauser M, De Hert M, Lacluyse K, Wampers M, Correll CU. Personal stigma in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a systematic review of prevalence rates, correlates, impact and interventions. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(2):155–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20040

67. Knaak S, Modgill G, Patten SB. Key ingredients of anti-stigma programs for health care providers: A data synthesis of evaluative studies. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(10)(11);Suppl 1:S19–S26. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405901s06

68. Ministerio de Salud (Minsal). Plan nacional de salud mental, 2017-2025. Santiago. 2017:1–234.

69. Geffner N, Salazar V, Mscayano F, Agrest M. Revisión de rogramas anti-estigma y a favor de la recuperación. Acta Psiquiátr Psicol Am Lat. 2017;63(3):189–202.

70. Dimenstein M. Psychiatric reform and the psychosocial care model in Brazil: in search of continuing integrated mental health care. RevCS. 2013;11:43–72. https://doi.org/10.18046/recs.i11.1566

71. Molina-Bulla C. Participación, políticas públicas, discapacidad mental / psicosocial y estigma: barreras y retos. Perspectivas Pol Publ. 2018;11(21):173–200.

Author notes

* Autora de correspondencia: pgrandon@udec.cl