Social Assistance and Informality: Examining the Link in Colombia

Asistencia social e informalidad: analizando la relación en Colombia

Assistência social e informalidade: analisando a relação na Colômbia

Social Assistance and Informality: Examining the Link in Colombia

Revista de Economía del Rosario, vol. 21, no. 1, 2018

Universidad del Rosario

Received: February 16, 2017

Accepted: January 02, 2018

Additional information

How

to cite this article: Saavedra-Caballero, F. & Ospina Londoño, M. (2018).

Social Assistance and Informality: Examining the Link in Colombia. Revista de Economía del Rosario, 21(1),

81-120. Doi: https://doi.org/10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/economia/a.6801

Abstract:

This paper presents evidence on the labor market effects of social assistance programs in the short and medium run. We evaluate the impact of a Conditional Cash Transfer —CCT— program “Familias en Accion” on informality at the individual level in Colombia. We include three different perspectives on informality that capture different aspects of the problem. We argue that, even though it is not a desirable result, being a beneficiary of social programs may create perverse incentives towards informality. We used survey data from the “Familias en Accion” program to identify whether the program had any effect on workers’ propensity to participate in the informal labor market in Colombia, both one and four years after the program’s implementation. To overcome the problem of unobserved time-invariant differences, our empirical strategy includes a combination of matching algorithms and difference-in-differences methodology. Our results show that worker’s informality condition may be affected by receiving CCT income.

JEL classification: E26, C14, H43

Keywords: informality, conditional cash transfers, evaluation.

Resumen:

Este

trabajo presenta evidencia sobre los efectos de los programas de asistencia

social en el mercado laboral, tanto en el corto como en el mediano plazo.

Evaluamos el impacto del programa de transferencias monetarias condicionadas

“Familias en Acción” sobre la informalidad en Colombia a nivel individuo.

Además, se realiza la evaluación utilizando tres perspectivas diferentes del

concepto de “informalidad” que capturan diversas facetas del problema.

Argumentamos que, a pesar de que no es un resultado deseable, ser beneficiario de

programas de protección social podría crear incentivos perversos como la

informalidad. Para alcanzar nuestro objetivo, utilizamos datos de la encuesta

del programa “Familias en Acción” para identificar si el programa tiene algún

efecto en la propensión de los trabajadores a participar en el mercado de

trabajo informal en Colombia, uno y cuatro años después de la implementación

del mismo. Nuestra estrategia empírica incluye una combinación de algoritmos de

pareo, además de la metodología de diferencias en diferencias. Nuestros resultados

muestran que la condición de informalidad de los trabajadores sí puede verse afectada

en caso de recibir una transferencia monetaria condicionada.

Clasificación JEL: E26, C14, H43

Palabras clave: informalidad, transferencias monetarias condicionadas.

Resumo:

Este trabalho apresenta evidencia sobre os efeitos dos programas de assistência social no mercado laboral tanto no curto quanto no mediano prazo. Avaliamos o impacto do programa de transferências monetárias condicionadas “Família em Ação” sobre a informalidade na Colômbia no nível indivíduo. Além disso, se realiza a avaliação utilizando três perspectivas diferentes do conceito de “informalidade” que capturam diversas facetas do problema. Argumentamos que a pesar de que não é um resultado desejável, ser beneficiário de programas de proteção social poderia criar incentivos perversos como a informalidade. Para conseguir o nosso objetivo, utilizamos dados do inquérito do programa “Famílias em Ação” para identificar se o programa tem algum efeito na propensão dos trabalhadores a participar no mercado de trabalho informal na Colômbia, um e quatro anos depois da implementação do mesmo. Nossa estratégia empírica inclui uma combinação de algoritmos de emparelhamento para além da metodologia de diferenças em diferenças. Nossos resultados mostram que a condição de informalidade dos trabalhadores sim pode se ver afetada no caso de receber uma transferência monetária condicionada.

Classificação JEL: E26, C14, H43

Palavras-chave: informalidade, transferências monetárias condicionadas.

Introduction

The effects of conditional cash transfers —CCTs— have been widely studied, with a special focus on developing and middle income countries. Rawlings and Rubio (2003) and Fiszbein et al. (2009) provide a wide review of CCTs’ effects over different outcomes, such as poverty, education and health. Latin America is recognized as the starting point of cct programs with Mexico’s Progresa in 1997 (later called Oportunidades), which was subsequently used as a model to expand ccts to countries such as Brazil with “Bolsa Escola” and “Bolsa Familia”, Peru with “Juntos” and Colombia with “Familias en Accion”. Although the effects of the CCT programs over different outcomes have been widely analyzed, there is still mixed evidence regarding the effects of CCTs on labor supply decisions and specifically in informality. Some studies report findings with different magnitudes (Fiszbein et al., 2009; Levy, 2008; Gasparini, Haimovich & Olivieri, 2009; Camacho, Conover & Hoyos, 2013), and others do not even find significant evidence (Filmer & Schady, 2014 Urdinola, Haimovich & Robayo, 2009; Edmonds & Schady, 2008; Skoufias & Di Maro, 2006).

The concern about this topic generally focuses on the eligibility criteria of CCTs that may generate perverse incentives for CCT programs’ beneficiaries to move out of the labor force or towards informality. While the eligibility criteria of a CCT program may not explicitly rule out people working in the formal sector, being a beneficiary from “Familias en Accion” may increase the probability to move towards the informal sector, since having a job in the formal sector increases individual income, reducing the probability of being eligible to be a beneficiary of the program. Our hypothesis is that benefits from social protection programs make individuals likely to maintain the features that benefit them and make them selectable for social benefits, such as a “registered” low income or being non-salaried (informal employment).

To test our hypothesis, we use evaluation data of the Colombian social assistance program “Familias en Accion”. This dataset contains information at the household and individual levels of beneficiaries before the execution of the program and for one and four years after its implementation. Regarding our empirical strategy, to overcome the problem of unobserved timeinvariant differences, we applied a combination of matching algorithms and difference-in-differences techniques. Our results show that a worker’s informality condition may be affected by receiving cct income.

We attempt to contribute to the existing literature to design more appropriate cct policies, especially in Latin America and the Caribbean. Therefore, this research has three distinctive features. First, given that the previous conclusions are mixed, we test our hypothesis by including three different perspectives of informality to achieve more conclusive results. Second, we use a very complete dataset from the Familias en Accion program that allows us to confidently apply quasi-experimental techniques to precisely determine the effects of social programs over the propensity towards informality. Third, our dataset allows us to compare the effects of a CCT program over time (the short and medium run).

This first section of the article provides a brief overview of the article. A review of the “Familias en Accion” program is presented in section two, and section three assesses the different definitions of informality and its relationship with social protection and conditional cash transfer programs. In section four, we describe the characteristics of our data, characterize our sample and develop our main assumptions. Section five describes the methodologies used to accomplish the impact evaluation and the results of the estimation. Finally, in section six, we discuss the results and provide some conclusions.

1. Familias en Accion

Familias en Accion is a social protection program in the form of a cct. It has been applied by the Colombian government as part of the Social Support Network, “Red de Protección Social —RPS—”, since 2001, with financial support from the World Bank and the Interamerican Development Bank. RPS is a public temporary social safety net that was created in 1999, with the aim of alleviating the effects of an economic recession and fiscal policy adjustments on extremely vulnerable populations in Colombia.

The Familias en Accion program was implemented only in municipalities that met specific features, including having fewer than 100,000 inhabitants, preferably when located in a rural area, having at least one financial institution, not being the capital of a regional district, having the essential infrastructure for health and education services, and not being located in the Coffee Region 1 (IFS-Econometria, 2004). Within the selected municipalities (as detailed in Attanassio et al., 2006), of the 1,024 municipalities in Colombia, 691 qualified for the program, another eligibility criterion for Familias en Accion beneficiaries is an instrument called System for Identification and Selection of Social Spending Beneficiaries (Sisben in Spanish).

Sisben classifies households into six different categories according to the household living conditions and defines potential beneficiaries of social programs as those people who are ranked among the three first levels (poor population). Sisben has evolved over time, 2 and the most important changes were focused on how to assess people’s living conditions. The first version of Sisben was active from 1995 until 2005 (the implementation period of Familias en Accion) and was estimated through the principal components statistical procedure. The groups of variables considered for the index’s construction were education, social security, demographics, income, house quality and equipment, and access to utilities (DNP, 2008).

Sisben uses the Unsatisfied Basic Needs Index and the Poverty Line as judgment standards to define its classification thresholds. Then, according to DNP (2008), an individual was considered poor if at least one basic need was unsatisfied and his income was 1.7 times below the poverty line. In a similar way, an individual was considered extremely poor if at least two basic needs were unsatisfied and his income was below the poverty line. These cut-points helped define the six different levels of the Sisben classification.

For a household to be enrolled by the National Planning Department —DNP— as a Familias en Accion grant recipient, it had to fulfill certain conditions. First, the household had to have children aged between 0 and 17 years. Second, it had to be classified as Sisben-1, which means that it had to belong to the poorest part of the population. As special cases, households that had children aged between 0 and 17 years and had been internally displaced or indigenous could also be enrolled as Familias en Accion beneficiaries.

The primary objective of Familias en Accion is to safeguard and foster human capital formation among children aged 0 to 17 from poor or vulnerable households through two different subsidies. The first subsidy is related to health and nutrition. It was provided to the beneficiary household on the conditions that children aged below 7 years were vaccinated and attended health and nutritional check-ups. In addition, mothers had to attend informational presentations on health, nutrition and contraception. The monthly CCT provided was approximately US$ 17.45 (COP 3 50,000) and was given per family, regardless of the number of children aged below 7 in the household.

The second subsidy is related to education and was provided to the beneficiary household for every child between 7 and 17 years who was enrolled in school and attended no less than 80 % of classes during the school year. As mentioned before, the monthly grant was given per child. In 2002, it was set at approximately US$ 5 (COP 14,000) for each primary school child and US$ 10 (COP 28,000) for each secondary school child.

In accordance with our Familias en Accion database, an average beneficiary household has six members, 4 one of which is a child aged below 7, and two of which are children between 7 and 17 years. Given that the legal minimum wage for Colombia in 2002 was around US$ 107.8 (COP 309,000), the relevance of Familias en Accion grant is evident, since an average Familias en Accion beneficiary household would receive a grant of US$ 41.8 (COP 120,000) each month, which represents 38.8 % of a legal minimum wage.

To determine the impact of the program on children health and nutrition, an initial assessment was conducted in 2004, and a second one was conducted in 2006. The information collected contains data from beneficiary and nonbeneficiary households with similar characteristics, aiming to estimate the impact of the program through quasi-experimental techniques. According to official reports (IFS-Econometría, 2004; DNP, 2008), the general conclusion of both evaluations is that the program effectively achieved its objectives, as it increased public expenditures on education, positively affected growth patterns among rural children and the weights of urban children, and reduced extreme poverty levels in rural areas, among others. 5

2. Informality

The origins of informality can be understood from two perspectives. The “exclusion” perspective claims that informality is imposed on individuals because of labor market segmentation (Rauch, 1991; De Soto, 1989; Harris & Todaro, 1970). In contrast to this position, the “exit” perspective argues that informality might be the individual’s choice instead of an imposition (Hirschman, 1970; Hirschman, 1981). As Levy (2007) and Levy (2008) explain, informality could be a result of individual´s optimal labor supply decisions.

However, there are several ways that academics have used to study informality. The characteristics agreed upon by most definitions are that informal employment involves economic activities that are not officially regulated or registered, that have irregular work conditions, that are labor intensive, where workers learn skills but those skills are usually not portable, 6 and entry and exit are easier than they are in the formal sector (Bacchetta, Ekkerhard & Bustamante, 2009; Bernal, 2009; Maloney, 2004).

Given that it is almost impossible to capture all these perspectives in one single definition of informality, and the complexity and peculiarities of the Colombian labor market, we used three different definitions of informality using social security, productivity and legal criteria. Each one of these definitions lets us understand informality from a distinct perspective and provide us with a wider view about informal employment.

From the social protection perspective, any worker who receives a payment for his/her job can be considered informal if he/she is not enrolled in social security by the hiring firm (Levy, 2008). However, not enrolling employees in social security is illegal. 7 Firm owners occasionally directly negotiate with future employees to exchange their social security contributions for a higher salary or “under the table” bonuses. Thus, we are uncertain whether this illegal activity that implies a lack of social security benefits is voluntary or compulsory.

From a productivity perspective, we consider Gasparini and Tornarolli’s (2007) standpoint that argues that informal workers display low productivity, which means they are unskilled and work at marginal jobs. Additionally, the International Labor Organization —ILO— characterizes the informal sector as primarily labor intensive, with a high requirement of low-level skills, and in which workers usually gain their skills at work. To approximate something as abstract as “productivity” or to represent the “lack of skills” with information contained in surveys, we follow Gasparini and Tornarolli (2007) and use the workers’ education level as a proxy. Therefore, any independent worker, farm boss or day laborer that receives a payment for his work that also has a low educational level (less than high school graduate) can be considered informal.

From a legal perspective, we will take advantage of some distinct legal attributes of the Colombian health system. According to Law 100 passed on December 23, 1993, all Colombian residents must be affiliated with the General System of Health Services. Thus, individuals who have a formal job (workers) must be enrolled by their employers in the contributive health system, and individuals who lack employment contracts must be enrolled by the government in the subsidized health system. Therefore, we assume that any worker that is enrolled in the Colombian contributive health system is considered formal, while when workers are enrolled in the subsidized health system it implies that they do not have an employment and are considered as informal.

To analyze the effects of ccts on informality using the previously mentioned definitions, we followed Levy’s (2008) approach, which argues that informality is a result of individual’s valuation of social programs. This valuation is influenced by the alternatives that the economic agent has costs and quality of the alternatives and by the ability to remove from the “package of benefits” those benefits they do not want to consume. It has to be clear that the individual’s valuation is independent from the design and quality of the institutions and programs that implement social protection. Moreover, workers’ decisions reflect their utility maximization, given the opportunities and incentives they have with each alternative, independently of the social program’s design.

We adapt Levy’s (2008) valuation scheme to a non-salaried worker’s utility. We denote Ci as the cost per worker of social protection programs, and βi as the worker’s valuation of social protection programs. Then, the utility a worker obtains from working in the informal sector (U) is the sum of his/her wage (informal_Wage) plus the value he/she gives to social protection (βi Ci ):

U= informal_Wage + βi Ci

It is worth mentioning that informal_Wage is low because, in order to receive social protection programs benefits (classify as Sisben-1), the individual’s monthly wage has to be very low. Otherwise, he would be excluded from social protection programs. As mentioned in Familias en Accion’s most recent operative manual, one of the employment status criteria to determine the access to the program is “to have an inadequate job 8 or the lack of salary”.

By design, βi ϵ[0,∞] because some individuals might value benefits more than their costs. Thus, we want to estimate whether receiving a Familias en Accion grant may increase βi (worker’s valuation of social programs). This would lead to an increase in the worker’ utility that will unintentionally direct him/her to valuate informality more by retaining the characteristics that make him/her a social protection beneficiary (such as a low registered income).

Considering previous evidence of social programs’ effects on labor force outcomes, Aterido, Hallward-Driemeir and Pages (2011) estimated that the expansion of the Seguro Popular program, which provided health insurance to Mexicans without social security, had an effect of a 0.7 pp reduction of the probability of being formally employed at the household level. At the firm level for the Seguro Popular program, Bosch and Campos-Vazquez (2010) found negative effects of between 3.8 pp and 4.3 pp in the creation of small and medium-sized formal jobs. They also found a reallocation of formal workers into informality.

Azuara and Marinescu (2013) used linear probability models with municipality fixed effects. They found no effect for the Seguro Popular over informality when analyzing the overall population, but they did find a statistically significant effect of a 0.9 pp increase in informality for less educated workers (9 years of education or less). They did not find any effects for Seguro Popular on the transitions between formal and informal jobs.

Specifically, for Colombia, Camacho et al. (2013) estimated the effects of the expansion of social programs in the early 1990s by the government on informality measured as employees between 12 and 65 years old who do not contribute to health insurance through employment. They found a 4 pp increase in informality once the health reform was imposed.

Santa Maria, Garcia and Mujica (2008) estimated a 14 pp increase in nonwage costs as a result of the 1993 social security reform in Colombia. They concluded that this increase in non-wage costs raised labor market segmentation and, as a consequence, informality.

In a similar way, Calderon-Mejia and Marinescu (2011) analyzed the impacts of Colombian unification of health and pension systems on informality, defined as workers covered by neither the contributive health insurance system nor the pension system. They found an increase in informality of 1.74 pp only over independent workers. They also analyzed the effect by firm size and for small firms (2-5 employees), and estimated an increase of 2.5 pp in full informality.

More recently, Barrientos and Villa (2015) estimated the labor force participation effects of the Familias en Accion program using a discontinuous regression design. They found significant effects only when sample restrictions on household composition and gender were applied. They found a statistically significant intention-to-treat effect on the probability of formal employment (employment with health insurance) among women of 3.2 pp for adults over 21 years. However, for men, they found no statistically significant effect.

As seen from these studies, the evidence is mixed, and the magnitude of the effect depends on the segment of the analyzed population. For this reason, we decide to include three different perspectives that account for the most common definitions of informality used in the literature. Additionally, through our empirical strategy, we intend to control for the differences between individuals that might affect the results.

3. Data

To apply our theoretical framework, we use data from the Familias en Accion program. We selected this database because its structure allows us to confidently apply quasi-experimental techniques. Moreover, there is no similar dataset for any social program in Colombia with the magnitude of Familias en Accion. 9

In general terms, the Familias en Accion database includes information from three different surveys: a baseline dataset collected in 2002, an initial follow-up completed in 2003, and a second follow up conducted between 2005 and 2006. This information is publicly available and can be disaggregated by household and individual. To compare the impact of Familias en Accion over time, we constructed two subsamples. The first one matches the baseline survey to the first follow-up, and the second one combines the baseline survey with the second follow-up. These subsamples allow us to explain the evolution of informality given social protection in the short and medium/long run.

Due to the labor market characteristics provided in the survey, we define workers as those who reported spending most of their time working the week prior to the survey or reported having a job. Additionally, to exclude child labor, only workers aged fifteen years and over were considered (according to Colombian Law 515 of 1999).

With respect to data collection issues, some municipalities received Familias en Accion payments before the baseline survey was conducted, thus causing data contamination. Therefore, we used only information from municipalities where the baseline survey was applied before the Familias en Accion cash transfers were given. Additionally, in the second follow-up survey, some families that belonged to the control group started receiving Familias en Accion subsidies. These families were not included in the estimations because their transition from the control to the treatment group distorted the characterizations of each group during the estimation process.

Regarding our perspectives to analyze informality, we created our informality variables as follows:

Informality 1 – Social protection perspective (Informality-1): This includes workers who were not enrolled in social security by the hiring firm. However, as previous evidence notes, the effect that social security programs have over small firms is higher (Calderon-Mejia & Marinescu, 2011; Santa Maria et al., 2008). For that reason, only for this definition, we focus only on workers who are not enrolled in social security and work in small firms (fewer than five employees).

Informality 2 – Productivity perspective (Informality-2): This includes nonsalaried workers who were unskilled. We followed Gasparini and Tornarolli (2007) to define informality by including non-salaried workers’ skills in our conceptualization. Due to data constraints, we used non-salaried workers’ education levels as a proxy. 10 Since the target population of Familias en Accion are Sisben-1 families, poor people with low education levels and economic limitations, we considered as “unskilled” those non-salaried workers who had not completed high school. Non-salaried workers can be identified as independent workers, farm bosses or day laborers.

Informality 3 – Subsidized health system perspective (Informality-3): This includes workers who were enrolled in the subsidized health system. To account for Colombia’s particular characteristics in our conceptualization we decided to use enrollment in the subsidized health system as the criterion to analyze informality. If a worker is enrolled in this system, we assumed that he/she prefers to be informal and to continue receiving public health services for free rather than making any contributions to obtain similar private health services as a formal worker.

Our first subsample (baseline with the first follow-up) captures the effects of Familias en Accion in the short run. It includes 15,110 observations composed by 5,918 treatment individuals and 9,192 control individuals. The average number of household members is 6, and the average numbers of children under 7 and children between 7 and 17 years are 1 and 2, respectively. Most of the individuals are men (approximately 58 %), and their average age is 37.

Regarding informality perspectives, for Informality-1, there are 2,426 treatment individuals and 6,766 control individuals. For Informality-2, there are 2,175 treatment individuals and 7,017 control individuals. Finally, for Informality- 3, there are 4,841 treatment individuals and 4,351 control individuals.

With respect to our subsample for the middle run (baseline with second follow-up), it contains 11,850 observations disaggregated into 6,180 treatment individuals and 5,670 control individuals. The average number of household members is 6, and the average numbers of children under 7 and children between 7 and 17 are 1 and 2, respectively. Most of the individuals are men (approximately 56 %), and their average age is 38.

Regarding informality types, for Informality-1 there are 1,148 treatment individuals and 4,185 control individuals. For Informality-2 there are 1,397 treatment individuals and 4,276 control individuals. Finally, for Informality-3, there are 3,122 treatment individuals and 2,551 control individuals.

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Causal Effects: Identification and Estimation

As mentioned earlier, we used quasi-experimental estimation techniques to evaluate the Familias en Accion program’s impact on informality in Colombia. Thus, certain considerations (such as differences in covariate values between informal and non-informal workers) demand special attention during the evaluation procedure. Moreover, the non-random assignment of municipalities to the treatment (Familias en Accion beneficiaries) or control groups may lead to imbalances across the covariates. 11 To avoid biased estimates of the impacts of informality in naïve comparisons of informal and non-informal workers, we applied propensity score matching to control for this confounding imbalance.

Through propensity score matching, we obtained the average treatment effect on the treated —ATT 12 —, which tells us whether workers who are Familias en Accion beneficiaries would have chosen being informal (binary outcome where 1 is being informal and 0 otherwise) and had they not received Familias en Accion assistance. Our counterfactuals were estimated 13 by calculating each worker’s propensity to be informal using a representation of his his/ her decision through a logistic regression of the binary category treatment/ control and then matching these workers with workers with similar propensities. Every decision is based on a function of the individual’s observed characteristics (covariates or confounders) summarized in a propensity score. 14

As in a randomized experiment, the matching techniques balance covariate distributions between treated and non-treated individuals as an identification strategy. 15 The treatment (T) is assigned independent of potential outcomes Y(i), where i=1 for informal workers and i=0 for non-informal workers. Therefore, we expect similar average outcomes if both groups receive the same treatment or if none of them do. This can be represented by the following equations:

These equations show that the average potential outcome for the treatment group is equal to the average potential outcome of the control group, had it been treated (equation 1). The average potential outcome for the treated group, had it not been treated, is equal to the average potential outcome of the control group with no treatment (equation 2).

Based on this, the att is estimated using the following equation, where E[Y(0)|T=1] represents the counterfactual:

However, the estimation of the ATT would only be correct if the treatment were randomly assigned, thus making the outcomes independent. Unfortunately, this was not the case for Familias en Accion, as the beneficiaries were selected based on specific characteristics. As a consequence, we use the conditional independence assumption —CIA— that ensures that the distributions of key covariates are balanced across the treatment and control groups. 16

In addition to the proper selection of covariates for each equation, there are other latent issues that we must address, such as the effectiveness of our matching procedure and the reduction of bias. Therefore, we must focus on how well balanced our covariates are. As D’Agostino and Rubin (2000) note, the propensity scores only serve as devices to balance the observed distribution of covariates across treated and comparison groups. Thus, the success of the propensity score estimation is assessed on the basis of this balance rather than by the fit of the models used to create the estimated propensity score. Another aspect to consider is the assumption of common support. 17 As noted above, PSM estimation performs under this assumption, which implies that all individuals who lack a match or were poorly matched will be omitted from the ATT estimation. Therefore, we look for a sample with high levels of “on support” observations because the larger the sample from which the impact of Familias en Accion was estimated, the more relevant and representative the results are.

At this point, we have specified our identification strategy (propensity matching score). However, there are many matching metrics available to achieve our goals. The best matching metric is the one that provides the best balance across our covariates of interest. This is the “nearest neighbor” with replacement. This metric considers each treated unit and searches for a control unit with the closest propensity score. We used the variation in this metric that includes replacement, which means that an untreated (control) individual can be used more than once as a match for treated units. 18 All our propensity score matching estimations were performed using Leuven and Sianesi (2003) Psmatch2 Stata module.

4.1.1. Difference-in-Differences and Matching

We combined propensity score matching —psm— with double-difference or difference-in-differences estimation —DiD— to address the potential for unobserved heterogeneity, since the DiD method allows the program selection to be based on unobserved variables. 19 As Khandker, Koolwal and Samad (2010) note, by jointly applying these techniques, we can address the nonrandom program placement that might bias the program’s effect while getting a better match control and projecting units on preprogrammed characteristics.

This estimator (DiD) compares a before-after estimation of treated individuals with a before-after estimation of non-treated individuals. This means (as mentioned by Bryson, Dorsett & Purdon, 2002) that the DiD estimator can cope with macroeconomic changes or changes in the lifecycle socio-economic status, as long as those changes affect both participants and non-participants similarly.

The equation for the DiD estimator is as follows:

where Y represents the outcome. T is a dummy that takes the value of 1 if the observation is in the treatment group or 0 if it is in the control group. P represents a post-treatment dummy that takes the value of 1 if the data are from a follow-up or 0 if the data correspond to the baseline.

4.2. Estimation and Results

As mentioned above, we performed all estimations using two different data subsets. The first subset includes information from the baseline and the initial follow-up, and the second includes information from the baseline and the second follow-up. Therefore, all results are presented for both data subsets in parallel. Initially, we present a naïve comparison between the treatment and control groups as a reference for further propensity score matching and DiD estimations.

To estimate this naïve difference-in-differences estimator, we used the following equation, which was originally proposed by Ñopo, Robles and Saavedra (2002) and modified for our purposes:

Effect FA (Familias en Acción) over inf=

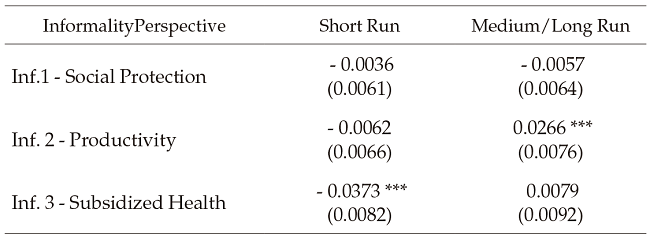

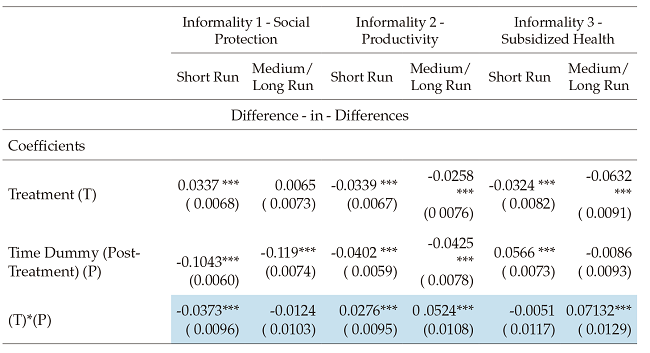

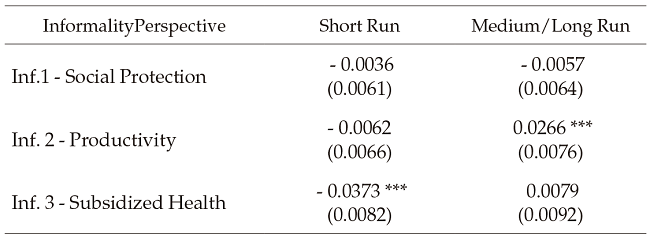

The impact that Familias en Accion obtained as a result of equation 5 for each type of informality are reported in table 1.

As observed in the table, most of the coefficients are not statistically significant, which makes them unsuitable for analysis. However, there are two statistically significant coefficients that can be examined. From these results, we can infer that, in the short run, Familias en Accion might reduce the probability to be informal type 3 (being enrolled in the subsidized health system) by 3.7 percentage points and, in the medium/long run, increase the probability to be informal type 2 (being a non-salaried low skill worker) by 2.7 percentage points.

Clearly, these naïve comparisons and estimators do not include features of each informality perspective, nor do they use comparable individuals. Therefore, to make this information truly comparable, we applied the propensity score matching technique and difference-in differences estimation as robust estimators, which allowed us to estimate the impacts of the Familias en Accion program over comparable individuals.

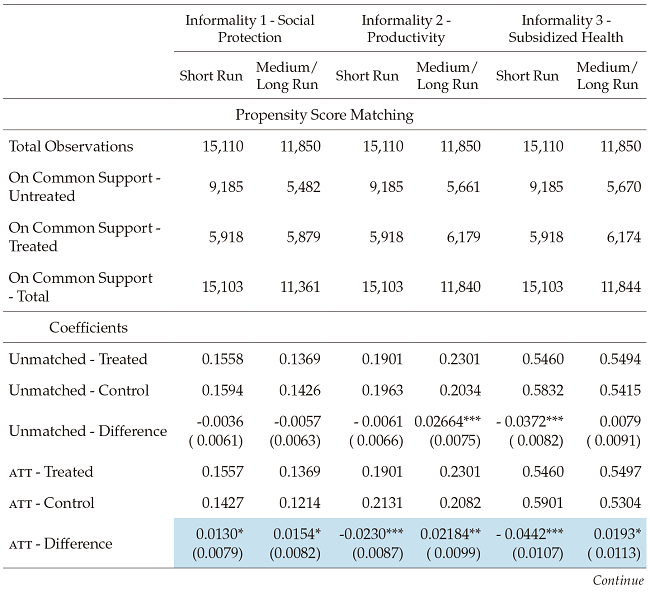

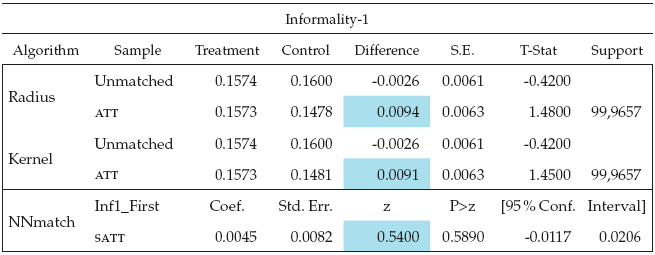

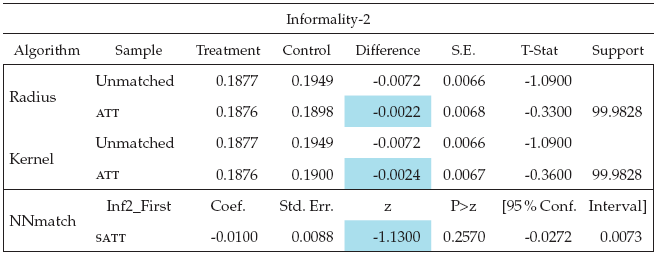

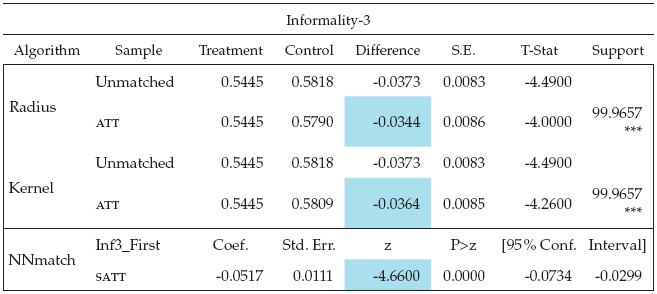

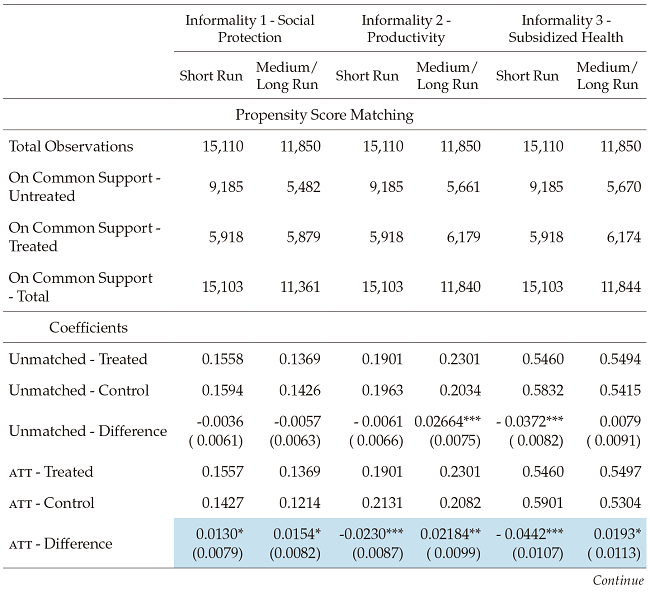

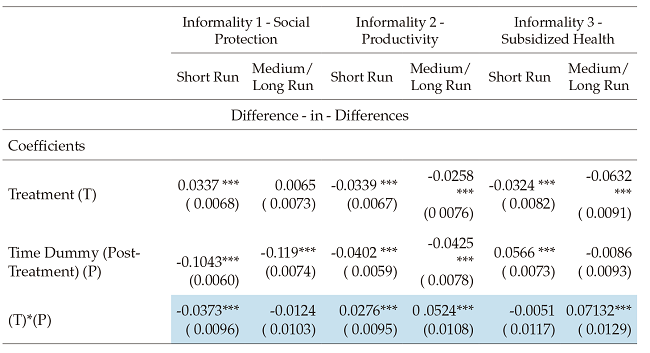

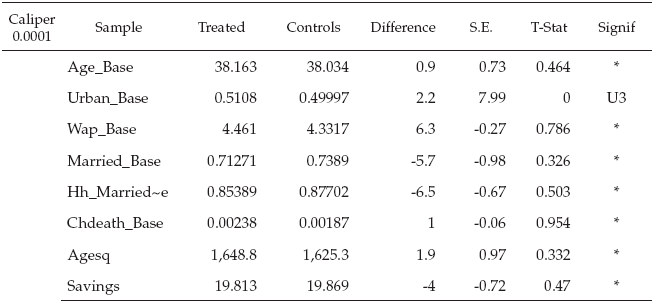

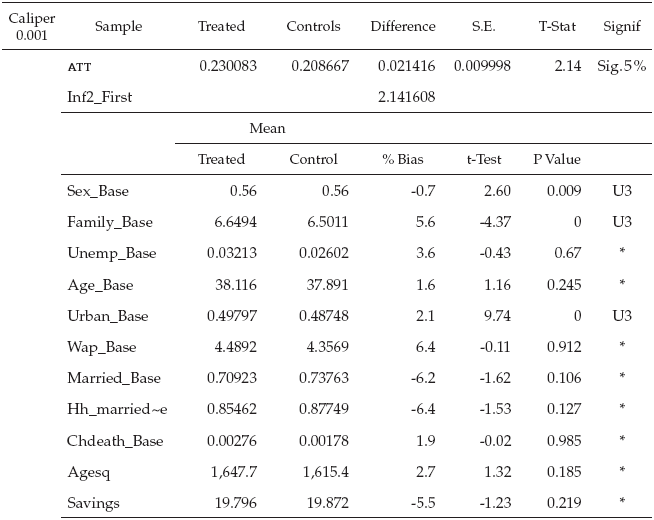

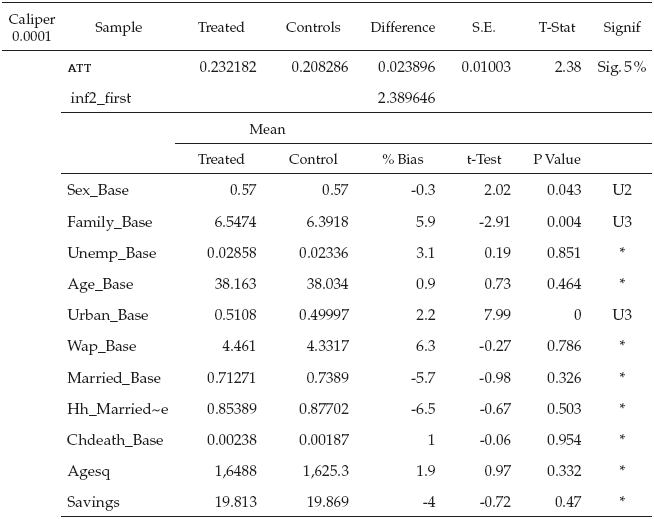

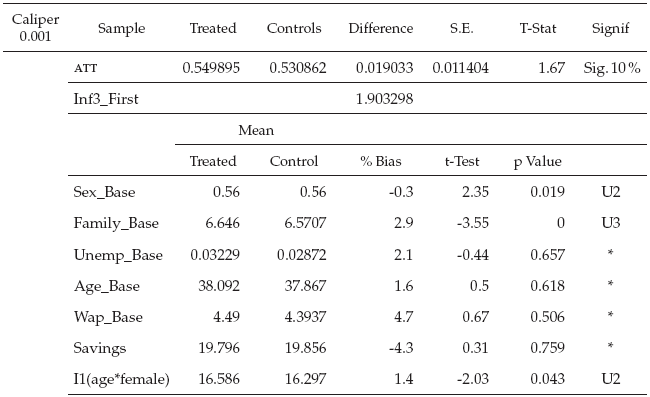

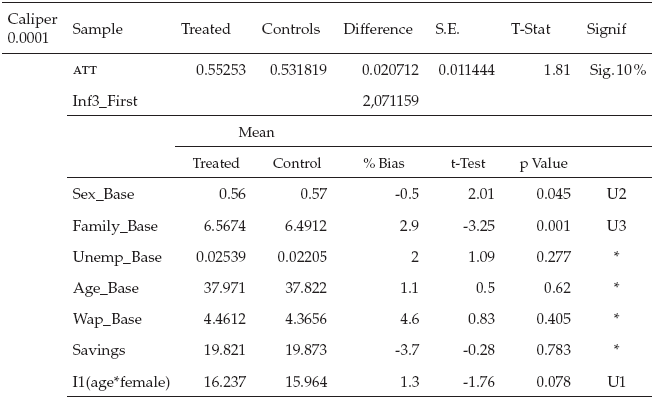

Initially, for psm, we applied the nearest-neighbor metric with replacement and included Cochrane and Rubin (1973) caliper matching. This helped us define a tolerance level when comparing propensity scores (we set the caliper tolerance at 0.01). 20 The psm results obtained are reported in the upper section of Table 2. Additionally, these psm results can be used as input for a DiD estimation process that will provide our estimators with additional information that could be interpreted more confidently with respect to the effects of Familias en Accion over informality.

As Heckman, Ichimura and Todd (1997) suggest, we performed a DiD estimation that includes psm specifications and results. As the effectiveness of the DiD estimator essentially depends on the characteristics of unobserved variables that could affect informality, the DiD estimation is performed only over the “on support” part of the sample after the psm procedure. The lower section of table 2 presents the estimates of the impact using the DiD technique.

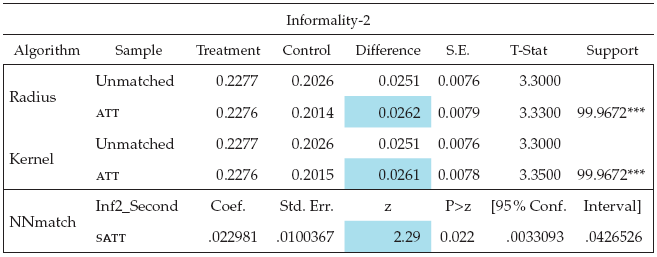

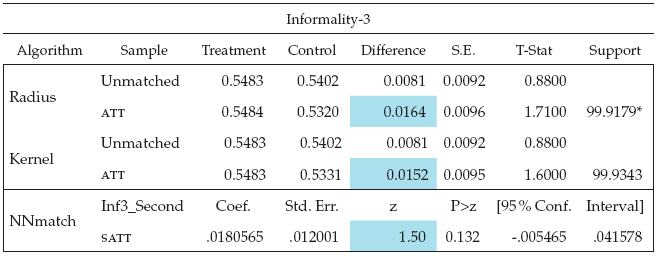

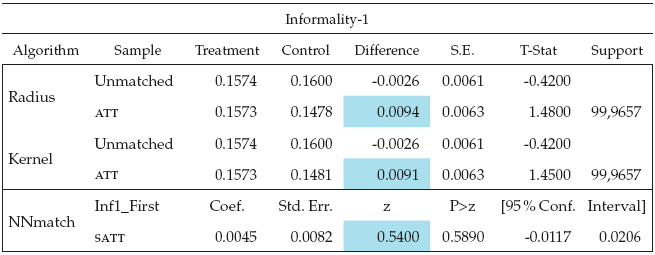

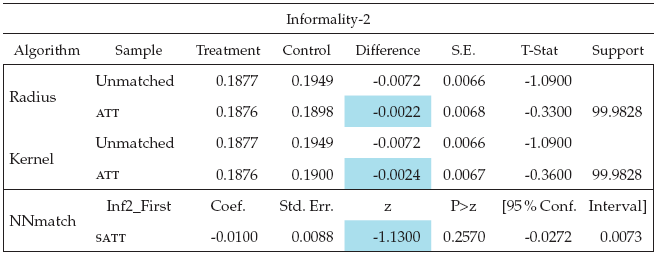

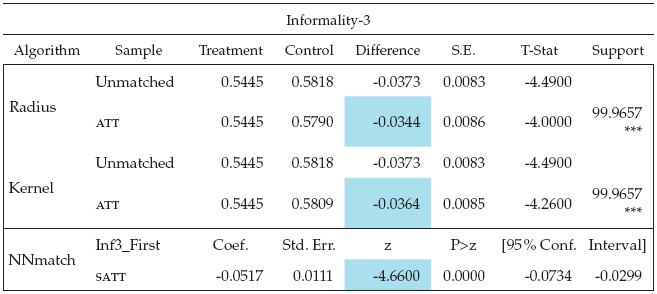

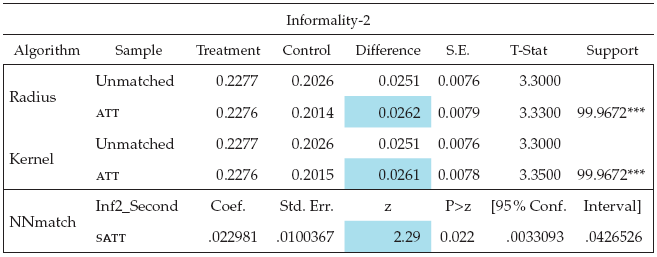

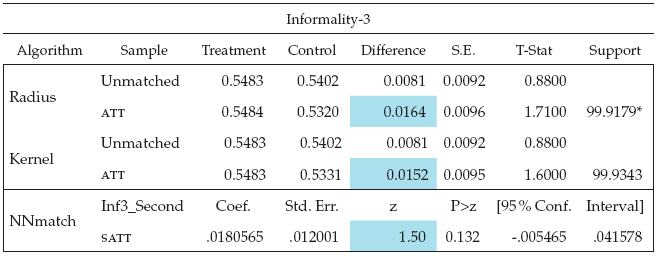

When analyzing the psm results, it can be seen that, in the short run, the Familias en Accion program’s impact on informality is negative for informality perspectives 2 (unskilled workers) and 3 (subsidiary health system beneficiaries). Thus, in the short run, being a beneficiary of the Familias en Accion program reduces the probability of being a non-salaried unskilled worker and reduces the probability of being enrolled in the subsidiary health system while working.

However, in the medium/long run, we obtained positive results from the att estimations for all informality perspectives. There is an increase of 1.54 pp in the probability of being a worker from a small firm who is not enrolled in the social security system. There is also an increase of 2.18 pp in the probability of being a non-salaried unskilled worker and an increase of 1.93 pp in the probability of being a worker who is enrolled in the Subsidiary Health System.

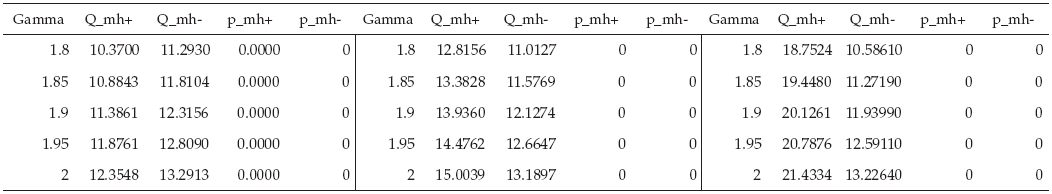

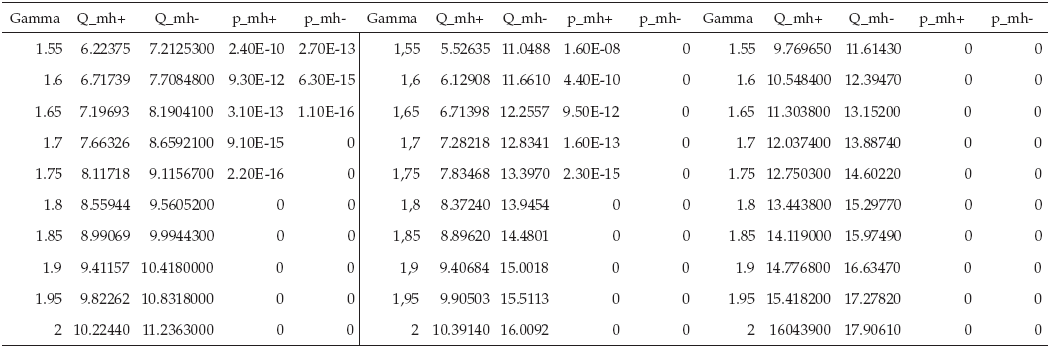

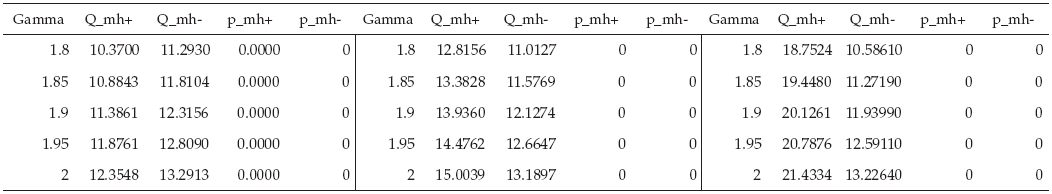

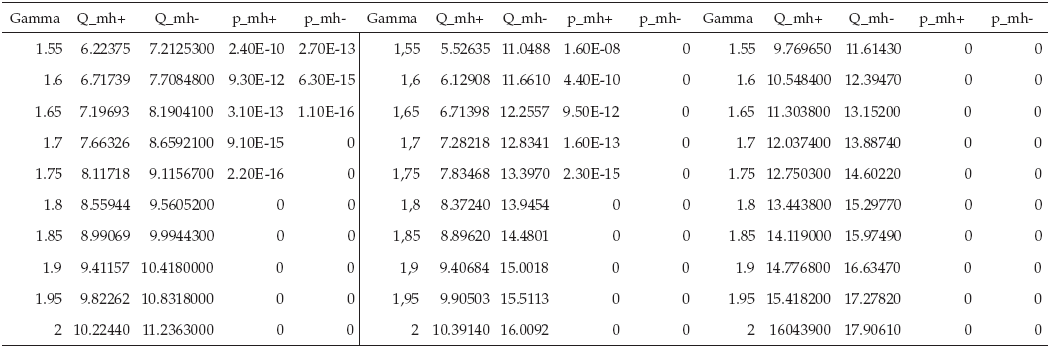

The complementary estimations that include different tolerance levels are presented in Appendix 2. They provide evidence of robustness because the results are not seriously affected despite different calipers. Similarly, in Appendix 3, we present the results obtained with different algorithms (such as Radius Matching and Kernel Matching), with the aim of showing that the nearest neighbor algorithm presented the best balance and that the specification was statistically significant for all cases. Finally, in Appendix 4, we present heterogeneity tests for each equation. 21

The findings presented in table 2 using psm could be broadly interpreted as the Familias en Accion program encouraging informality when workers make their labor decisions in the medium/long run. However, psm results can be used as an input for a DiD estimation process, which will provide us with estimators that contain additional information and could be interpreted more confidently regarding the effects of Familias en Accion over informality.

Our DiD results show an opposite effect than the one obtained through the psm technique for Informality-1 (social security informality) in the short run. While the psm shows an increase of this type of informality in both the short and medium/long runs, DiD shows a decrease of 3.73 pp in the short run and an insignificant effect in the medium/long run. This could be interpreted as a fading of the negative impact of Familias en Accion over workers not enrolled in social security (working in small firms) along time.

For informality-2 (non-salaried unskilled workers), there is a 2.76 pp increase in the short run and 5.24 pp increase in the medium/long run. These results concur with the psm results for this type of informality in the medium/long run, which estimated a 2.18 pp increase. This could be interpreted as workers making riskier decisions, such as being informal rather than looking for a formal job. The Familias en Accion income could play the role of a financial safety net that allows unskilled individuals to start their own business or to take jobs that are not regular but that pay more.

Informality-3 (workers enrolled in the subsidized health system) shows non-significant effects in the short run through the DiD technique. However, in the medium/long run, the Familias en Accion program has a positive effect on the probability of being enrolled in the Subsidized health system and concurrently working 7.13 pp. However, the magnitude of the effects measured through the psm and DiD differs for the Informality type 3 in the medium/long run. Both estimation techniques show an increase of this type of informality. This might occur because workers realize that, by keeping their Sisben status, they can have access to a subsidized health system and also to Familias en Accion benefits. Therefore, by being informal, they earn income working without making any contributions, have access to free health services, and receive cash subsidies from Familias en Accion.

Conclusions

This paper examines the effects of social protection programs on a broad definition of labor market informality. Social protection programs, such as conditional cash transfers, are known to be a powerful tool to combat inequality and increase welfare in a society. However, ccts may have also significant side effects.

Positive income shocks (such as CCTs) may create perverse incentives for workers to move out of the labor market. First, due to CCTs programs’ eligibility criteria (low income), individuals might want to keep their low registered income by working in a non-registered job (informal job). Further, CCTs may act as a financial safety net that drives workers towards risky ventures, such as informality.

The social protection program “Familias en Accion” was developed as a social safety net for Colombia’s poorest people after the economic crisis the country suffered during the 1990s. The results that this program delivered to its target population (children and teenagers) were positive, such as increasing school enrollment, reducing childhood malnutrition and even discouraging child labor (Attanasio et al., 2006).

However, little has been said regarding its effects over different outcomes such as informality. That is why we examine the causal effect of social assistance programs on worker’s informality using the Familias en Accion database. To this end, we computed several matching algorithms and employed the nearest neighbor propensity score matching with a caliper and a difference-indifferences estimation for three different definitions of informality. We extend the existing literature on cct and informality by considering three different perspectives of informality. In addition, we exploit several key features of our dataset to examine the short and medium/long run effects.

Overall, we found that Familias en Accion affected workers’ probability of not being enrolled in social security (defined as Informality-1) only in the short run, decreasing it by 3.73 pp. This could be interpreted as workers leaving those jobs that did not enroll them in social security (small firms) as a first reaction once they receive Familias en Accion money. However, the effect in the medium/long run is insignificant, which can be interpreted as workers making decisions based on criteria not related to social security enrollment. This result is related to Barrientos and Villa (2015), who estimated the labor force participation effects of Familias en Accion and found a statistically significant intention-to-treat effect on the probability of formal employment (employment with health insurance) among women of 3.2 pp for adults over 21 years. Although we control our estimations by gender, we don´t estimate causal effects by gender.

Regarding non-salaried unskilled workers’ perspective (Informality-2), Familias en Accion fostered informality in the short and medium/long run. In the short run, the probability of being a non-salaried unskilled worker increased by 2.76 pp and almost doubled in the medium/long run (5.24 pp increase). This reflects workers making riskier decisions (such as starting their own businesses or looking for an informal job) that pay higher wages but is neither regular nor accomplished by labor laws. In this case, Familias en Accion would play the role of a financial back up or safety net.

Finally, regarding workers enrolled in the subsidized health system (Informality- 3), Familias en Accion affected them only in the medium/long run by increasing the probability of being a worker enrolled in the subsidized health system by 7.13 pp. This could be interpreted as the awareness of workers regarding the benefits of being informal (no contributions, free health services and extra money from Familias en Accion). The benefits from social protection programs are more valuable to individuals than benefits from formal employment if they consider that public services compensate for formal employment benefits. For example, if subsidized and contributory health services are practically the same in Colombia, then individuals would rather not pay for contributory services (through wage discounts) because they will receive almost the same services for free in the subsidized health system.

These findings suggest that, in the short run, Familias en Accion has a significant positive effect on the propensity towards informality only over those workers who are less productive (low skills or unskilled). Regarding workers who lack social security, the effect of Familias en Accion disappears over time (insignificant in the medium/long run). We also found a significant, highly positive impact for workers who are enrolled in the subsidized health system.

Overall, these results show that people who are working but non-salaried and receive cct benefits are prone to become informal, especially in the medium/ long run. Unskilled workers are the most sensitive to these benefits because they are affected immediately (short run) and the effect over them persists over time (medium/long run). This may occur because benefits from social protection programs are more valuable to individuals than benefits from formal employment, especially if workers are less productive (Unskilled workers have less information about Familias en Accion and the conditions for inclusion/exclusion from the program). Moreover, in Colombia, the social assistance beneficiary status is defined through the Sisben (System for Identification and Selection of Social Spending Beneficiaries) that classifies individuals based on their living conditions. 22 Because beneficiaries constitute the poorest part of the population, income is one of the most important weights. This might induce beneficiaries from social assistance programs, in an attempt to retain their benefits, to have low registered income levels or to not register incomes at all, which may lead them to informality. 23

Additionally, individuals may consider that public services compensate for formal employment benefits (subsidized and contributory health services are practically the same in Colombia). Therefore, we speculate that individuals perceive money from cct programs as a financial security net that allows them to incur in more dangerous but also more rentable ventures (because of tax and contribution evasion) such as informality.

Our results coincide with previous studies that analyzed the effects of being eligible of social programs in Colombia. While Camacho et al. (2013) found a 4 pp increase in informality for the subsidized health system, our estimations show a 7.13 pp increase in informality. Our estimations are higher than Camacho´s results, this is explained because we estimate effects for the poorest population of Colombia, while they cover the whole country.

References

Aterido, R., Hallward-Driemeier, M. & Pages, C. (2011). Does Expanding health insurance beyond formal-sector workers encourage informality? Measuring the impact of Mexico’s Seguro Popular. Policy Research Working Paper Series, 5785, The World Bank.

Attanasio, O., Fitzsimons, E., Gomez, A., Lopez, D., Meghir, C. & Mesnard, A. (2006). Child education and work choices in the presence of a conditional cash transfer programme in rural Colombia. Paper Wp06/01. London: The Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Azuara, O. & Marinescu, I. (2013). Informality and the expansion of social protection programs: evidence from Mexico. Journal of Health Economics, 32(5), 938-950.

Bachetta, M., Ekkehard, E., & Bustamante, J. (2009). Globalization and informal jobs in developing countries. A joint study of the International Labour Office and the Secretariat of the World Trade Organization. Geneva: World Trade Organization and International Labour Organization.

Barrientos, A. & Villa J. (2015). Antipoverty transfers and labor market outcomes. Regression discontinuity design findings. The Journal of Development Studies, 51(9), 1224-1240.

Bernal, R. (2009). The informal labor market in Colombia: identification and characterization. Bogotá: School of Economics, University of los Andes.

Bosch, M. & Campos-Vazquez, R. M. (2010). The trade-offs of social assistance programs in the labor market: the case of the “Seguro Popular” program in Mexico. Working Papers Series of the Centro de Estudios Economicos 2010-12. Mexico D.F.: Centro de Estudios Economicos , El Colegio de Mexico.

Briceño, B., Cuesta, L. & Attanasio, O. (2011). Behind the scenes: managing and conducting large scale impact evaluations in Colombia. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 3(4), 470-501.

Bryson, A., Dorsett, R. & Purdon, S. (2002). The use of propensity score matching in the evaluation of active labour market policies. London: Departament of Work and Pensions.

Calderon-Mejia, V. & Marinescu, I. (2011). The impact of Colombia’s pension and health insurance systems on informality. Technical Report n.º 62338. IDB Working Paper.

Caliendo, M. & Kopeinig (2008). Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. Journal of Economic Surveys, 22(1), 31-72.

Camacho, A., Conover, E. & Hoyos, A. (2013). Effects of Colombia’s social protection system on workers’ choice between formal and informal employment. The World Bank Economic Review, 28(3), 446-466.

Cochrane, W. & Rubin, D. (1973). Controlling bias in observational studies: a review. Sankhyā: The Indian Journal of Statistics, Series A (1961-2002), 35(4), 417-446.

D’Agostino R. B. Jr. & Rubin, D. B. (2000). Estimating and using propensity scores with partially missing data. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 95, 749-759.

De Soto, H. (1989). The other path: the invisible revolution in the third world. New York: Harper Row.

Departamento Nacional de Planeación —DNP— (2008). Programa Familias en Acción: impactos en capital humano y evaluación beneficio-costo del programa. Bogota: Departamento Nacional de Planeacion.

Edmonds, E. & Schady, N. (2008). Poverty alleviation and child labor. Policy Research Working Paper 4702. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Filmer, D. & Schady, N. (2014). The medium-term effects of scholarships in a low-income country. Journal of Human Resources, 49(3), 663-694.

Fiszbein, A., Schady N., Ferreira, F., Grosh, M., Keleher, N., Olinto, P. & Skoufias, E. (2009). Conditional cash transfers: Reducing present and future poverty. World Bank Policy Research Report. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Gasparini, L., Haimovich, F., & Olivieri, S. (2009). Labor informality of a poverty-alleviation program in Argentina. Journal of Applied Economics, XII(2), 181-205.

Gasparini, L. & Tornarolli, L. (2007). Labor informality in Latin America and the Caribbean: Patterns and trends from household survey microdata. Working Paper n.º 46. La Plata: Centro de Estudios Distributivos, Laborales y Sociales (Cedlas).

Harris, J. R. & Todaro, M. P. (1970). Migration, unemployment, and development: a two-sector analysis. American Economic Review, 60(1), 126-42.

Heckman, J., Ichimura, H. & Todd, P. (1997). Matching as an econometric evaluation estimator: Evidence from a evaluating a job training programme. The Review of Economic Studies, 64(4), 605-654.

Hirschman, A. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty: responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Cambridge: Harvard University Press

Hirschman, A. (1981). Exit, voice, and loyalty: further reflections and a survey of recent contributions. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. Health and Society, 58(3), 430-453.

IFS-Econometría S.A. (2004). Evaluación del impacto del programa Familias en Acción: subsidio condicionados de la red de apoyo social. En Documentación de la Base de Datos de la Segunda Medición – Primer seguimiento. Bogota: Unión Temporal ifs/Econometría S.A./SEI.

Khandker, S., Koolwal, G. & Samad, H. (2010). Handbook of impact evaluation. Washington DC: The World Bank.

Lee S. (2006). Propenstity score adjustment as a weighting scheme for volunteer panel web surveys. Journal of Official Statistics, 22(2), 329-349.

Levy, S. (2007). Social policy, productivity and growth. Background paper for the regional study, Beyond Survival: Protecting Household from Health Shocks in Latin America. Washington DC.: World Bank.

Levy, S. (2008). Good intentions, bad outcomes: social policy, informality and economic growth in Mexico. Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

Leuven, E., & Sianesi, B. (2003). PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing. Statistical Software Components S432001, Boston College Department of Economics.

Maloney, W. (2004). Informality revisited. World Development, 32(7), 1159-1178.

Ñopo, H., Robles, M. & Saavedra, J. (2002). Una medición del impacto del Programa de Capacitación Laboral Juvenil PROJoven. Documento de Trabajo n.º 36. Lima: Grupo de Análisis para el Desarrollo —GRADE—.

Nupia, O. (2011). Anti-poverty programs and presidential election outcomes: Familias en Acción in Colombia. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes.

Ospina, M. (2010). The indirect effects of conditional cash transfer programs: an empirical analysis of Familias en Accion (dissertation). Georgia State University, Atlanta, United States.

Rauch, J. (1991). Modelling the informal sector formally. Journal of Development Economics, 35(1), 33-47.

Rawlings, L., & G. Rubio (2003). Evaluating the impact of conditional cash transfer programs. Lessons from Latin America. Policy Research Working Paper n.º 3119. Washington, DC: Workld Bank.

Rosenbaum, P. & D. Rubin (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41-55.

Santa Maria, M., Garcia, F. & Mujica, A. (2008). Los costos no laborales y el mercado laboral: impacto de la reforma de salud en Colombia. Working Paper 43. Bogotá: Fedesarrollo.

Skoufias, E. & Di Maro, V. (2006). Conditional cash transfers, work incentives and poverty. Policy Research Working Paper 3973. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Smith, J. & Todd, P. (2005). Does matching overcome LaLonde’s critique of non- experimental estimators? Journal of Econometrics, 125(1-2), 305-353.

Urdinola, D. F, Haimovich, F. & Robayo, M. (2009). Is social assistance contributing to higher informality in Turkey? Background paper for Country Economic Memorandum (CEM) – Informality: Causes, Consequences, Policies. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Appendix 1: List of Covariates and Covariate Balance

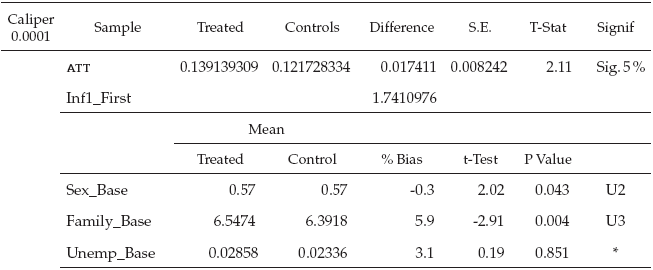

In order to verify if the covariates were balanced across treatment and control groups, we used the following criteria for balance:

Even though most of our covariates are balanced (‘covariates’ means are not significantly different across treatment and control groups), we identified some covariates with a U3 level of unbalance. In that case, we applied the rule of a thumb that states that a percentage of bias of less than 10 % is acceptable. None of our unbalanced covariates surpasses a 10 % bias.

Appendix 2: Sensitivity to proximity (calipers)

Data subset: Baseline vs. First Follow-Up

Data subset: Baseline vs. Second Follow-Up

Appendix 3: Matching algorithms

Data subset: Baseline vs. First Follow-Up

Data subset: Baseline vs. Second Follow-Up

Appendix 4: Heterogeneity Test (Rosenbaum Bonds)

Data Subset: Baseline vs. First Follow-Up

Data Subset: Baseline vs. Second Follow-Up

Notes

1 The Coffee Region, in central Colombia, received special assistance as a consequence of the 1995 earthquake.

2 By 2017, there were three different versions of Sisben.

3 Central Bank of Colombia, TRM (Market Representative Exchange Rate) COP 2,864.79 per dollar at December 31st, 2002.

4 Rounded numbers based on the first following information with 15,110 individuals and 7,267 households as sample.

5 There are also studies that analyze the impact of fa on areas other than those for which the program was created, such as intra-household time allocation (Ospina, 2010) and voters’ behavior (Nupia, 2011).

6 As Bacchetta et al. (2009) mentions, these skills are accepted only by a limited number of firms or might not be recognized at all by future employers.

7 Levy (2008) states that hiring salaried workers but not enrolling them in social security is an illegal act committed by the firm and not by the worker.

8 An inadequate job is defined as the presence of at least one person in the household who is working but is not enrolled in social security.

9 Familias en Accion was the first large-scale evaluation of a social intervention implemented in Colombia (Briceño, Cuesta & Attanasio, 2011).

10 We decided to use a proxy because it would be almost impossible for us to properly measure workers’ skills (including hard and soft skills) based on the available data.

11 Familias en Accion targets the poorest people (Sisben-1). Therefore, individuals self-select into the program.

12 We decided to use ATT instead of ATE since, as Caliendo and Kopeinig (2008) note, to estimate ATE, we would have to construct the counterfactual of the treated, had they not been treated (as in ATT); and the counterfactual of the non-treated, had they been treated.

13 According to Rosenbaum and Rubin (1983), it is not possible to know each individual’s propensity because that would imply having complete information about selection. Therefore, these propensities have to be estimated.

14 By summarizing each individual’s characteristics, propensity score matching solves the “curse of dimensionality” that covariate matching would have because of continuous and/or numerous confounders.

15 The core framework that the propensity score matching method employs attempts to reproduce that of randomized experiments. Nevertheless, as Lee (2006) mentions, it is important to note two important differences between propensity score matching and randomized experiments. First, propensity score matching only balances the observables between treated and control samples, while randomized experiments balance the distributions of both observables and unobservables. Second, the estimates from propensity score matching can be considered a weighted average of the estimates from many small randomized experiments.

16 We have two main assumptions. 1) The set of characteristics we have chosen includes all relevant differences between the treatment and control groups. 2) The distribution of the characteristics in the control group we selected resembles the distribution of the treatment group.

17 All our matching estimations show a common support of 95 % and above.

18 By allowing for replacement in the nearest neighbor technique, we reduced bias and increased the average matching quality. Nevertheless, this also increased the variance of the att estimators.

19 Nevertheless, the DiD method requires that unobserved variables be time-invariant.

20 An issue with caliper matching is the difficulty in setting the tolerance level a priori (Smith & Todd, 2005). Therefore, we performed several estimations with different caliper levels. Our results (balance and common support) were not particularly sensitive to these variations. Hence, we decided to set the caliper at 0.01, as is used in most impact evaluation studies.

21 As seen in Appendix 4, there is some evidence of heterogeneity in our estimations.

22 The first version of the Sisben index that was active from 1995 until 2005 classified individuals´ living conditions primarily on agents’ economic resources (DNP, 2008).

23 This may also happen because of the lack of information regarding the conditions for inclusion/exclusion from Familias en Acción. Most of the people that are beneficiaries from Familias en Acción do not know how the Sisben index is estimated. The only information they have is that beneficiaries are the poorest people, and they try to keep that status.

Author notes

* Department of Finance, School of Economics and Finance, Universidad Eafit, Medellin, Colombia. Corresponding author: fsaaved1@eafit.edu.co. Department of Finance –School of Economics and Finance, Universidad Eafit, carrera 49 No. 7 Sur – 50 Office 26-514. Telephone (57 4) 2619500 ext. 8745.

fsaaved1@eafit.edu.co