10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/economia/a.14801

Natalia Arango-Ramírez 1

Andres Camacho-Murillo 2

* We thank Colombia Ministry of National Education for the provision of relevant datasets. We also thank Crimson Interactive Pvt. Ltd. (Enago) for their assistance in manuscript editing.

1 Independent Researcher.

![]() natiaran3@hotmail.com

natiaran3@hotmail.com

2 Corresponding autor. Department of Economics, Universidad Externado de Colombia.

![]() giovanni.camacho@uexternado.edu.co.

giovanni.camacho@uexternado.edu.co.

![]() 0000-0002-6182-0972

0000-0002-6182-0972

Recibido: 28 de agosto de 2024

Aceptado: 11 de noviembre de 2024

Para citar este artículo: Natalia Arango-Ramírez, N., & Camacho-Murillo, A. (2023). Transforming Lives: The Positive Impact of School Retention Strategies on the Probability of Students' Dropout in Medellin. Revista de Economía del Rosario, 26(2), 1-34. https://doi.org/10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/economia/a.14801

Abstract

This study assesses the causal effect of school retention strategies on the probability of school dropout in Medellin, Colombia. The probit model is estimated using microdata on enrollment published by the Ministry of National Education and data on beneficiaries of school retention programs, year 2019. Three impact evaluation methods are employed to obtain the counterfactual group of each school retention program: Self-Selected Comparisons, Propensity Score Matching, and Endogenous Treatment-Effects. Results from the latter method show that the probability of school dropout is lower for students enrolled in the School Meals Program, School Transportation Program, or Complementary School Day Program, compared to the counterfactual groups, by -1.0 pp, -3.17 pp, and -2.97 pp, respectively. However, the study finds heterogeneous effects around school retention programs, which are explained by students' social class, nationality, and sex.

Keywords: school dropout; school meals program; school transportation program; Complementary school day program; probit model; impact evaluation.

JEL Classification: I25, H22

Resumen

Este estudio evalúa el efecto de las estrategias de retención escolar sobre la probabilidad de deserción estudiantil en Medellín, Colombia. El modelo probit se estima utilizando microdatos de matrícula consolidados por el Ministerio de Educación Nacional y datos de beneficiarios de programas de retención escolar, año 2019. Los resultados muestran que los estudiantes con acceso al Programa de Alimentación Escolar, Programa de Transporte Escolar, o Programa de Jornada Escolar Complementaria reducen la probabilidad de deserción escolar en -1.0 pp, -3.17 pp, y -2.97 pp, respectivamente. Sin embargo, el estudio encuentra efectos heterogéneos significativos en torno a los programas de retención escolar que se explican por la clase social, la nacionalidad y el sexo de los estudiantes.

Palabras clave: deserción escolar; programa de alimentación escolar; programa de transporte escolar; programa de jornada escolar complementaria; modelo Probit; evaluación de impacto.

Clasificación JEL: I25, H22

Resumo

Neste estudo, avalia-se o efeito das estratégias de permanência escolar sobre a probabilidade de evasão escolar dos estudantes em Medellín, Colômbia. O modelo probit é estimado usando microdados sobre matrículas consolidadas pelo Ministério da Educação Nacional e dados sobre beneficiários de programas de permanência escolar, de 2019. Os resultados mostram que os estudantes com acesso ao Programa de Alimentação Escolar, ao Programa de Transporte Escolar ou ao Programa de Jornada Escolar Complementar reduzem a probabilidade de abandono escolar em -1,0 p.p., -3,17 p.p. e -2,97 p.p., respectivamente. No entanto, no estudo, encontram-se efeitos heterogêneos significativos em torno dos programas de permanência escolar que são explicados pela classe social, nacionalidade e gênero dos estudantes.

Palavras-chave: evasão escolar; programa de alimentação escolar; programa de transporte escolar; programa de jornada escolar complementar; modelo probit; avaliação de impacto.

Classificação JEL: I25, H22

1. Introduction

Education is one of the most contributing social factors to the countries' social and economic growth and development (Murillo & Gallón, 2018). As a human capital factor, education improves the quality of life of citizens by providing them with access to better jobs, wages, and cultural conditions (Cardona et al., 2007). Further, education drives business innovation (Camacho-Murillo et al., 2020) and contributes to overcoming poverty and reducing inequalities (Manzano & Ramírez, 2012). Amid the frenetic race to tackle climate change, education has the power to influence on people's pro-environmental behaviors (Pérez-Arango & Camacho-Murillo, 2022). Any public and private effort resulting in an increasing access to education and low school dropout rates is crucial for society.

School dropout is considered the abandonment of the academic system by students (Manzano & Ramírez, 2012). Thiscan be considered as an obstacle when it comes to accessing opportunities for the development of skills to obtain better working, cultural, and quality of life conditions. There are consequences associated with school dropout include intergenerational continuity of poverty and social inequalities, which negatively affects social integration and democracy strengthening (Espíndola & León, 2002). School dropout has a major negative effect on the students' economic, social, educational, and psychological environment, as the possibilities for their personal and economic growth decrease (Silvera, 2020). Therefore, the reduction of school dropout rates accounts for the success of public education policies adopted by different countries (García, 2016).

According to the Secretary of Education of Medellin (SEM), major progress has been made in Medellin about educational coverage over the last few years; however, challenges persist for students who start a school year and fail to finish it (SEM, 2020). Medellin is the second largest city in Colombia, accounting for 5 % of the national population in 2023 (DANE, 2023). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the decline in the city's dropout rate was significant, reaching 2.74 % in 2019 (SEM, 2020); however, the pandemic increased the dropout rate to 3.47 % (SEM, 2020). The pandemic accelerated the digital gap among students in local institutions (Cespedes-Parra & Camacho-Murillo, 2022), which may have led to higher dropout rates in Medellin, as was the case at the national level (Morales, 2021).

School dropout can be explained by different socioeconomic and cultural theories, both internal and external to the school system (Manzano & Ramírez, 2012), as well as by student engagement (Archambault et al., 2022). Variables are classified as protective risk factors, including the education level of the household head, household income, and sex (Rodríguez, 2021); harmful risk factors, such as pregnancy, family type (single-parent or two-parent), employment status, overage, and family history of psychoactive substance use (Rodríguez, 2021), and engagement-associated factors, including students' behavior, emotions, and cognition (Fredricks et al., 2004). Public policies oriented to school retention are external factors that have not been fully explored in the Latin American literature, except for Jiménez and Jiménez (2016) in Argentina, Carrillo (2014) in Mexico, and De Janvry et al. (2011) in Brazil. The policymakers face the challenge of improving the living conditions of students to ensure that more children and young people graduate from basic education (Jiménez & Jiménez, 2016).

Medellin has adopted three relevant public strategies to reduce school dropouts in public establishments, although the results have not been quantitatively assessed yet. The eligibility criteria of beneficiaries are based on the System of Identification for Social Assistance Beneficiaries (SISBEN, for its Spanish acronym), students' school levels (grades), and social vulnerability conditions (disability, place of living (rural), ethnicity, victimization). The School Meals Program (PAE, as per its Spanish acronym) provides students with complementary balanced food such as milk, complementary meal (snacks and other supplements), or lunch, as per the national mandate (UApA, 2021). The PAE among public schools depends on the school hours per day, restaurant conditions, and sociodemographic characteristics of students (Decreto 1852, 2015). The School Transportation Program offers round-trip mobility alternatives for students living in the city or within its jurisdiction (SEM, 2020). Finally, the Complementary School Day offers 4 hours of extracurricular activities per week for students in the areas of environment, science and technology, bilingualism, sports and recreation, culture, and citizenship education (Alcaldía de Medellín, 2014).

There is consensus in the literature on the positive effects of school retention strategies on the reduction in school dropout (Carrillo, 2014; Jiménez & Jiménez, 2016); however, the literature has not yet identified whether the decrease in school dropout is heterogeneous or not between subgroups around students' sociodemographic characteristics, including the students' socioeconomic level (Abril et al., 2023; Barragán & Lozano, 2022; Nita et al., 2021), gender (Gómez-Restrepo et al., 2016; Rodríguez, 2021), and nationality. The latter group of students covers migrants who face diverse financial and emotional challenges when settling in a country; challenges that affect their school permanence (Tovar, 2024).

This study aims to assess the causal effect of school retention strategies on the students' probability of dropout in Medellin, analyzing two hypotheses. First, whether the probability of dropout is lower in students who have access to PAE, School Transportation, and/or Complementary School Day, respectively, compared to those who do not have access to these programs. Second, whether the expected lower probability of school dropout by students with access to these retention programs differs between students around relevant sociodemographic variables, such as Strata (economic conditions), nationality, and sex.

School dropout is not a sporadic event; it requires prevention and treatment alternatives. According to Espinoza et al. (2014), there is a clear relationship between school dropout, poverty, and social exclusion. Consequently, finding whether school retention programs reduce the probability of dropping out of school in Medellin is a crucial step to understand the effectiveness of public intervention on social wellbeing, as well as to guide the public policymakers in their decisions on education. This study uses consolidated enrollment data from Colombia's Ministry of National Education (MEN), year 2019, and information on beneficiaries of the retention strategies from Medellin's Secretary of Education (SEM). The probit model is used to estimate the probability of student dropouts. Three impact evaluation methods are employed to estimate and comparatively analyze the average treatment effects of each retention program on students' dropout probability: the Self-Selected Comparisons method, the Propensity Score Matching method, and the Endogenous-Treatment Effects method (Gertler et al., 2016; StataCorp., 2023). A literature review on the effects of public policies on school dropout is presented in Section 2. Section 3 evaluates data and estimates the probit model under the three impact evaluation methods. Section 4 discusses the results of the study. Section 5 provides conclusions and implications.

2. Literature Review

Various internal and external factors under study in the literature affect school dropout. Rodríguez (2021) found the risk factors with the greatest influence on student dropout and classify them into protective and harmful factors. These protective risk factors include the characteristics that make student dropout less probable, such as the higher education level of household head, greater household income, doing extracurricular activities, and sex. Some harmful risk factors are those that increase the probability of dropout, including pregnancy, living in a single-parent home, employment status, belonging to a family with a history of psychoactive substance use, and being overage (Rodríguez, 2021; Román, 2013); the latter is when a student is two or three years older than the average age expected in a grade (MEN, 2023).

One of the relevant topics, although not studied extensively, is the effect of school retention-related public policies on student dropout rates. These policies tend to improve the school retention rates as the direct and indirect costs of going to school, including food and transportation, are reduced (Rute & Verner, 2011). Lower costs via direct money transfers have a positive impact on the students' attendance, who no longer must work to contribute to their household and support their families financially or caring for their siblings while their parents are working (Nita et al., 2021; Jiménez & Jiménez, 2016). The programs that help to reduce costs through the direct provision of food, school transportation (Carvalho et al., 2010), and extended day activities (Tenti, 2010) are also essential to boost school retention. The following is an analysis of empirical studies on the effects of school retention strategies in Latin American countries, including Colombia, which names the gaps that this research aims to fill.

Carrillo (2014) evaluated the impacts of the "Prepa Sí" program, implemented in the city of Mexico, on student dropout. This program includes money transfer sent to students attending classes in the upper middle and high school levels during the school year. Using a binomial probit model, Carrillo (2014) found that the program reduces the probability of school dropout and improves the academic performance of Mexican students. Pedroza et al. (2021) assessed the impact of the Full-Time School Programs (Programa Escuelas de Tiempo Completo, in Spanish) in a Mexican institution and found that the program successfully lengthens the time students stay in school, thereby reducing the academic lag among students, and the students' probability of dropout in those who belong to a lower socioeconomic stratum.

Jiménez and Jiménez (2016) evaluated the effects of the Universal Child Allowance program on adolescent school dropout in Argentina. Using propensity score matching with data from the National Household Expenditure Survey, the authors concluded that the program significantly reduces school dropout levels. In Ecuador, Rosales (2020) used a difference-in-difference model to assess the impact of PAE on the permanence of second- to seventh year students, and found that the student promotion rate to the next grade increases by 10 % in students with access to the program. In contrast, Espínola and Claro (2010) found that the results of the programs created to combat school dropout in Chile, called School Retention Support Scholarship (Beca de Apoyo a la Retención Escolar bare its acronym in Spanish) and Pro-Retention Subsidy (Subvención Pro Retención, SPR its acronym in Spanish), are insufficient and ineffective as the desired results were not achieved. The negative results found in Chile are due to methodological mistakes in the inclusion/exclusion of students from the program; the lack of financial resources to cover the opportunity cost of dropping out; and the omission of efficient monitorization of allocated resources to educational institutions (Espínola and Claro, 2010).

Colombia has developed school retention programs, including the PAE, School Transportation, and Complementary School Day. Caicedo et al. (2021) evaluated the effect of the PAE on student dropout in Ciudad Bolívar (Bogotá), using data from the men and through student characterization. The study showed that the PAE significantly contributes to primary school students' retention rates, and its success lies in the fact that students can access food that cannot be supplied to their homes daily (Caicedo et al., 2021). In Cali, Vergara, and Rodríguez (2015) found that the PAE contributes to the decrease in students' dropout and reprobation rates in the city, as well as to the increase in academic performance.

The Complementary School Day is another strategy adopted in Colombia that allows students to stay in school for added hours to the regular school day. This does not imply that students can attend more regular classes during this time, but they participate in formative, recreational, and sports activities that keep them away from the social risks of abandoning school. By using family fixed-effects models in panel data from 2007-2008, statistics from SISBEN and men, García et al. (2013) reported that all-day schooling reduces the probability of school dropout between 1 and 2 percentage points, whereas repetition decreases this possibility from 2 to 5 percentage points.

School transportation is crucial for the students' access to and retention in the educational system, mainly in rural or geographically remote areas. When the State provides school transportation through contracted service routes, it contributes to the regularity and punctuality of students' attendance to class, which tends to reduce school dropout rates (Leal and Oliveira, 2022). However, no empirical research evaluating the effect of transportation on reduced student dropout rates are found in the literature. This lack of studies may be partly due to the allocation of student quotas prioritizing the proximity of their residence to the educational entity, which leads to a low demand for transportation services.

In summary, the literature shows that the retention strategies associated with direct and indirect money transfers have contributed to the decrease in student dropout in various Latin American cities and countries. Most studies in Latin America have applied (unconsciously) the Self-Selected Comparisons method to get the counterfactual group of treatment. This practice usually leads to a selection bias, as the factors that explain the individuals' participation in a program (enrollment) are correlated with outcomes (Gertler et al., 2016). This study wants to contribute to the literature by applying an impact evaluation method that controls endogeneity. In the literature, no evidence exists on the impact of transportation programs on school dropout rates. There is major interest in studying naming whether the impact of school retention strategies is homogeneous for all beneficiaries or if differences exist between students that may be explained by the students' sociodemographic characteristics.

3. Data and Method

3.1 Data

This study conducts a retrospective impact evaluation of School Meal Program (PAE), School Transportation Program (Transp), and Complementary School Day Program (JEC) on the probability of dropping out in the city of Medellin in 2019; this is a city that accounts for 5 % of Colombia's total population. The study uses the enrollment registry consolidated and confirmed by the men in the Integrated Enrollment System (SIMAT). The dataset considers the entire enrolled population of the city, which reached 299,071 students in 2019; therefore, the use of population expansion factors for estimations in this paper are not necessary. The data allow us to find those students from public elementary and high schools who drop out anytime during the school year (intra-year dropout), as well as their socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. There is another database sourced from the SEM is employed to find the beneficiaries of retention programs analyzed in this paper. Overall statistics show that 3.8 % of public elementary and high school students dropped out in 2019; around 67 % of students received benefits from the PAE program; 3.6 % were enrolled in the School Transportation program; and 3.05 % took part in the Complementary School Day program.

All public schools can receive support for the programs from SEM at the beginning of each year, although eligibility criteria apply for PAE and School Transportation. For PAE, the SEM initially chooses students already registered by each public school in SIMAT; then, the principal of each public school and a special committee choose the beneficiaries giving a combined priority to i) full-time students, ii) early childhood students, iii) ethnic population, armed conflict victims, and disabled people (progressively from early childhood to superior levels), and iv) people enrolled in SISBEN (Rendón, 2024). The School Transportation strategy applies to students who live in neighborhoods where public local transport does not cover mobility needs, reside farther than 12.5 blocks from their schools (mainly in rural areas), are enrolled in SIMAT, and live in vulnerable households identified through the SISBEN score (sem, 2024). For the Complementary School Day program, all students can be enrolled participate (there is no eligibility criteria).

In 2019, the 0-to-100 SISBEN range helped authorities in the education sector of Medellín find the most and the least vulnerable individuals in terms of people's characteristics, including their dwelling and household conditions (the closer to zero, the greater the level of vulnerability). Figure 1 shows that most students concentrate on a 37-point SISBEN score with a standard deviation of fifteen points (Figure 1a), and between school levels 3rd and 8th (Figure 1b).

Figure 1. Distributions of students by SISBEN and school levels

Source: the authors based on data from the SEM.

Table 1 shows, initially, that 98.4 % of the students with access to PAE and 97.9 % who used the Transportation Program did not drop out within the school year. Furthermore, 99.1 % of those who took part in the Complementary School Day program remained at school. This contingency analysis shows the likely positive impact of the three retention programs in reducing student dropout.

Table 1. School dropout by student retention program (%)

Source: the authors based on data from the MEN and SEM.

Figure 2 shows statistical distributions of the PAE, Transp, and JEC programs highlighting important characteristics. The choice of PAE beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries closely follows the distributions of SISBEN and school levels (Figures 2a and 2b). Similarly, Figures 2c to 2f show the statistical distributions of Transp and JEC beneficiaries and non-beneficiaries over SISBEN scores and school levels, respectively, and show that the distributional pattern of Transp is much closer to PAE than the pattern of JEC to PAE. The presence of perfect or quasi-perfect correlation between the three retention programs is rejected through the tetrachoric correlations test, which is designed for binary explanatory variables that may have common correlation patterns (Brown, 1977; StataCorp, 2021).

Figure 2. Distributions of PAE, Transp, JEC over SISBEN and school levels

Source: the authors based on data from the sem.

3.2 Method

The probability of students' dropout (Pi) is modeled using the probit model of Equation (1) under a standard normal cumulative distribution function Φ (•) and a linear combination of independent variables xj through and index function z (Wooldridge, 2020). Heteroscedastic errors are found and corrected using standard errors adjusted for clusters (Wooldridge, 2020). The model has the following specification:

The index function z has the common specification z = β'x+u, where the regressors are assumed to be exogenous (including the school retention programs), and the stochastic error term is u ~ iid N(0, σ2) . Based on the eligibility criteria for the programs and data availability, three impact evaluation methods are used to estimate the counterfactuals for each of the three school retention program s following) Gertler et al. (2016) and StataCorp. (2023). These are the Self-Selected Comparisons method, the Propensity Score Matching method, and the Endogenous Treatment-Effects method.

Self-Selected Comparisons Method

The self-selected comparisons method compares the dropout probabilities of students who participate in any of the programs (the treatment groups) with those who do not participate (the counterfactual groups), assuming both groups hold similar characteristics and expectations of returns from the programs (Gertler et al., 2016). Equation (1) is, therefore, estimated with a linear combination of independent variables Xj as shown in Equation (2):

where PAE, Transp, and JEC are the key dichotomous variables in this study that capture treatment. The retention programs are assumed not to be correlated with the outcome (the probability of1 dropout). The variable PAE is equal to 1 if the student is a beneficiary of PAE, and 0 otherwise; Transp is equal to 1 if the student has access to the School Transportation Program, and 0 otherwise; and JEC is equal to 1 if the student is a beneficiary of the Complementary School Day Program, and 0 otherwise.

There are several controls are included in Equation (2). Stratum012 takes the value of 1 if the student belongs to socioeconomic strata 0, 1, or 2, and 0 if they belong to the other strata (3, 4, 5, or 6). This is a proxy variable for the socioeconomic level of students and their families. Overage is a variable that takes the value of 1 if the student is overaged (they are at least 3 years older than the average age needed in the grade), and zero otherwise. Repeat is equal to 1 if the student is a repeater and zero otherwise. Victim is equal to 1 if the student is a victim of an armed conflict (in a situation of displacement, disassociated from armed groups, son/daughter of demobilized adults, and victim of anti-personnel mines, among others), and zero otherwise. Ethnic is a variable that takes the value of 1 if the student belongs to an ethnic group (Indigenous, Black, or Afro-Descendants), and 0 otherwise. The variable Disable takes on the value of 1 if the student has a type of disability (visual, intellectual, multiple, hearing, physical, psychosocial, or mental), and zero otherwise. Rural takes the value of 1 if the student lives in a rural area and zero if the student comes from an urban area. HouHead takes the value of 1 if the student is the head of household and zero otherwise. Colombia is equal to 1 if the student is Colombian and zero from other countries. Finally, Woman is a dichotomous variable that takes the value of 1 if the student is female and zero if the student is male.

Descriptive statistics of control variables show that 79 % of students belong to strata 0, 1, and 2; 4.9% are overage; 5% are repeaters; 5.9% are victims of the armed conflicts; 1.9 % of students belong to an ethnic group; 3.5 % suffer from some type of disability; 5.9 % reside in rural areas; 4.3 % are children of mothers who are heads of households; 87 % of the students are Colombians (the remaining are mainly from Venezuela); and 50.3% of the students are female. The variance inflation factor test yields a value of 1.02, showing that a perfect or quasi-perfect multicollinearity between the control variables is not present (Wooldridge, 2020). A low association between independent variables is confirmed through tetrachoric correlations.

A reduction in the probability of school dropout is expected to be greater for the treatment groups (beneficiaries of any of the programs cj: PAE, Transp, or JEC) compared to the effect for the control groups, ceteris paribus. The average treatment effects (ate) of school retention programs are estimated as:

Propensity Score Matching Method

The Propensity Score Matching (PSM) method belongs to quasi-experimental methods that mimic the randomized assignment method (Gertler et al., 2016). PSM helps to construct an artificial counterfactual group that has remarkably similar characteristics to the treatment group through statical techniques (Rosenbaum and Rubin, 1983). In this study, the method estimates the predicted probability (the propensity score Pic) that a student will be enrolled in a program c based on the eligibility characteristics that determine enrollment (X): SISBEN, school levels (Levels), and vulnerability conditions (Victim, Ethnic, and/or Disable). The heteroskedastic probit model by Harvey (1976) is employed to estimate the Pic of each retention strategy to capture for heteroskedastic parameters. The model specification is:

The denominator in Equation (4) shows a variance that can vary over some regressors ωj; this is,  . The linear combination of independent variables Xj (the index function 0 for the propensity score) includes the best combination of eligibility characteristics (linear and quadratic) as presented in Appendix A: The estimated propensity scores

. The linear combination of independent variables Xj (the index function 0 for the propensity score) includes the best combination of eligibility characteristics (linear and quadratic) as presented in Appendix A: The estimated propensity scores  for all students in the treatment groups are matched with the group of

non-enrolled students that have the closest propensity score. Consequently, Equation (1) is estimated with the estimated propensity score of each retention program (

for all students in the treatment groups are matched with the group of

non-enrolled students that have the closest propensity score. Consequently, Equation (1) is estimated with the estimated propensity score of each retention program ( ) using the indexe function z of Equation (5).

) using the indexe function z of Equation (5).

The ATE at the population after matching is obtained from the estimation of Equation (6), which shows the mean difference between the probability of dropout by students who access the program(s) and the probability of drop-out by students who do not access the program(s), the counterfactual group.

The box plots in Figure 3 show that the ATE from the PSM method applied to PAE, Transp, and JEC were able to balance all the covariates between treatment and control groups.

Figure 3. Balance Plots of PSM for Retention Programs

Source: the authors based on data from the men and sem.

Endogenous Treatment-Effects Method

This method controls for endogeneity that can arise from unobservable covariables that affect treatment assignments and the outcomes (StataCorp., 2023). The method in this study allows for correlation between students' unobservable characteristics that; explain the probability of participating in each program, and the students' probability of dropout. The probit model is employe d to estimate the probability of taking part in each retention program  , as shown in Equation (7), using cluster error correction:

, as shown in Equation (7), using cluster error correction:

The linear combination of independent variables Xj includes the combination of eligibility characteristics as done for the estimation of propensity scores in Appendix A. Thus, Equation (1) is estimated including  of each retention program and the covariates (the controls) that are directly associated with the probability of dropout as shown in Equation (8).

of each retention program and the covariates (the controls) that are directly associated with the probability of dropout as shown in Equation (8).

The Endogenous Treatment-Effects method follows Equation (9), where Pi is the observed probability of dropout, Pi1 and Pi0 are the potential dropout probabilities when students receive and do not receive the retention programs, respectively, and is  observed probality of getting the retention program (the binary treatment). We let the stochastic error terms of Pi1 and Pi0 functions εi1 and εi0) to be correlated with the error of

observed probality of getting the retention program (the binary treatment). We let the stochastic error terms of Pi1 and Pi0 functions εi1 and εi0) to be correlated with the error of  function (vi). This is,

function (vi). This is,  (Wooldridge, 2010).

(Wooldridge, 2010).

The Average Treatment Effect (s obtained as follows:

Heterogeneous Effects

There is a potential risk of estimating the impact of school retention programs when homogeneous impacts are assumed for all the recipients (Gertler et al., 2016). Our database holds student-characterizing regressors that are not associated with the eligibility criteria of beneficiaries. These characterizing variables (Zk) are Stratum012, Colombia, and Woman. We assess the potential heterogeneous effects of school retention programs on the probability of student dropout a round each characterizing factor for the Self-Selected Comparisons method in Equation (11), for the PSM method in Equation (12), and for the Endogenous Treatment Effects method in Equation (13).

4. Results

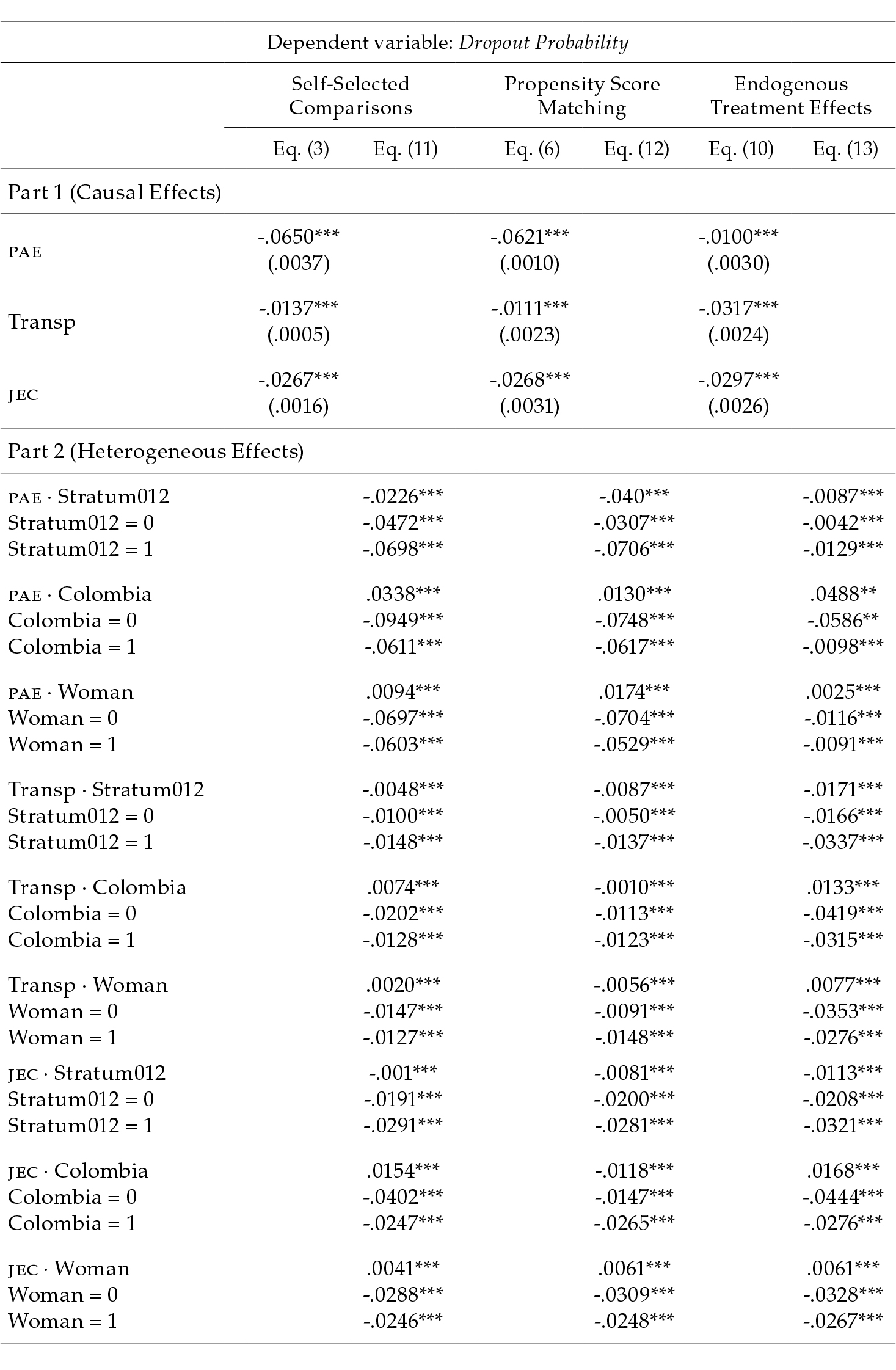

This section shows the ate results for the Self-Selected Comparisons method, the Propensity Score Matching method, and the Endogenous Treatment-Effects method in two analytical parts. Part 1 in Table 2 displays the ATE of retention strategies on school dropout probabilities following Equations (3), (6), and (10). The ATE coefficients are used to evaluate the first research hypothesis; this is, whether students enrolled in school retention programs (PAE, Transp, or JEC) have a greater reduction in the probability of dropout compared to students in the counterfactual group. Appendix A displays the estimated propensity scores of each retention program from Equation (4). Part 2 in Table 2 shows the ATE of retention strategies by subgroups of students based on Equations (11), (12), and (13), with which the second hypothesis is examined; this is, whether the expected lower dropout probabilities of students enrolled in school retention programs, compared to the non-enrolled students' dropout probabilities, differ among students based on their socioeconomic level (Stratum012), nationality (Colombia), and sex (Woman).

4.1 Causal Effects

Results from the three methods show that students enrolled in the school retention strategies under study, PAE, Transp, JEC, have a lower probability of dropping out compared to students who are not beneficiaries of these programs (Table 2, Part 1). The magnitude of the ate in the Self-Selected Comparison method and the PSM method are not significantly different from each other, suggesting high adequacy of the selection criteria, and the patterns of statistical randomness when choosing beneficiaries based on these criteria. However, the presence of endogeneity, confirmed through the control-function approach (StataCorp., 2023), supports the ate results from the Endogenous Treatment Effects method. There are unobservable characteristics of school dropout probabilities that are correlated with the retention programs- the treatment assignments. Factors that change school dropout probabilities, including mental health issues, can be correlated with school meal programs, school transportation, and complementary activities. PAE ensures nutritious food that is essential for students' well-being; transportation increases the motivation to attend classes without mobility stress and anxiety; and recreational activities increase students' retention as they liberate stress while improving their mental and body health conditions.

Results from the latter method in Table 2, Eq. (10) show that, controlling for endogeneity, students' dropout probabilities fall, on average, by -1.0 pp if students are beneficiaries of the PAE (from 2.34 % to 1.34% at the mean levels) by -3.17 pp if students are enrolled in the School Transportation program -Transp (from 3.30% to 0.13%), and by -2.97 pp if students receive Complementary School Day -JEC (from 3.88% to 0.91%). The results are statistically significant at the 1 % critical value.

Table 2. Average Treatment Effects of School Retention Strategies

Source: the authors based on data from the men and sem

These results show that the three retention strategies under study help to reduce the probability of student dropout in official schools from Medellin, being Transp the most effective in reducing school dropout, after controlling for endogeneity, followed by JEC. The results are in line with the findings by Leal and Oliveira (2022) and Carvalho et al. (2010), who consider that school transportation contributes to decreasing dropouts and increasing attendance. The findings also support results by Pedroza et al. (2021), García et al. (2013), and Tenti (2010), who show that extending school hours favors school retention and prevents students from lagging or repeating grades. These results mirror the findings by Caicedo et al. (2021) for Ciudad Bolívar (Bogotá) and Rosales (2020) for Ecuador, that estipulate that school meal programs promote class attendance and retention.

Results from the estimation of Equation (4) on the propensity scores of retention programs (presented in Appendix A) are of interest in this paper, as these propensity scores are estimated based on eligibility criteria. The estimated coefficients show that students are more likely to receive each program if SISBEN scores increase; there is a 1 % statistically significant quadratic shape of the propensity score of PAE and Transp as expected from Figure 2. Conversely, students are less likely to enroll in the programs as school levels increase, although there is also a quadratic shape that is statistically significant at the 1 % level. Students who are war victims are more likely to receive PAE. Disabled students are more likely to receive the benefits of PAE and/or Transp, and less likely to receive JEC. Ethnic students are more likely to receive PAE and/or Transp, and students from rural areas are more likely to receive any of the retention programs.

4.2 Heterogeneous Effects of School Retention Programs

The Average Treatment Effects of school retention programs on students' dropout probabilities can differ around students' socioeconomic level, nationality, and sex. Initial estimations from Equation (2) (not reported in Table 2) show that students with low socioeconomic levels are more likely to drop out as compared to students with more favorable socioeconomic conditions; Colombian students are less likely to drop out compared to students with other nationalities; and women are less likely to abandon the school compared to men. The results from Equations (11), (12), and (13) identified in Table 2, Part 2, show that the ate of school retention strategies on school dropout probabilities differ among subgroups of students. The results are statistically significant at the 1 % level. Figure 4 summarizes the results obtained from the Endogenous Treatment Effects method Equation (13), as they differ from those obtained from the Self-Selected Comparisons method and the PSM method; the latter two show biased estimates that arise from endogeneity issues already evaluated.

Figure (4a) shows that while the probability of dropout of students receiving PAE is reduced by -1.29 pp if the student belongs to a low socioeconomic level (Stratum012), the same probability is only reduced by -0.42 pp in students of greater socioeconomic levels. Thus, the reduction in the probability of dropout for students who are beneficiaries of the PAE is 0.87 pp greater for students in stratum 0, 1, 2 compared to students from the control group. This result implies a more positive effect of PAE in the reduction of school dropouts on economically vulnerable students, which is the expected outcome in programs of this kind.

Figure 4. Average Treatment Effects from PAE, Transp, and JEC by Subgroups

Source:

Figure (4a) also shows that the effect of PAE in Medellin is greater for the immigrant population than for Colombians, since for the former, the probability of dropping out is reduced by -5.86 pp when receiving the PAE, whereas, for locals, the probability of dropping out is reduced by -0.98 pp in PAE beneficiaries. Therefore, a decrease in the probability of student dropout for PAE beneficiaries is 4.8 pp greater in students who are not Colombians. Considering the results for female students, the coefficients in Figure (4a) show that the decrease in the probability of student dropout for PAE beneficiaries is 0.25 pp greater if the student is male compared to the control group. This is, although the probability of female student dropout is reduced by -0.9 pp when receiving the PAE, the probability of student dropout among the male population is reduced by -1.16 pp for PAE beneficiaries. This result leads to unbalances in the student dropout statistics between men and women in the short term from the implementation of PAE. In the long term, this implies a more favorable labor inclusion for men than for women, thanks in part to lower school dropout rates for men that arise from access to PAE.

Figure (4b) analyzes the ate from the Transportation program. The reduction in the probability of dropout for beneficiaries of the School Transportation program is 1.71 pp greater for students of low socioeconomic status (stratum012) compared to students in the control group (-3.37 pp vs -1.66 pp, respectively). Therefore, the positive effect of transportation in the reduction of school dropout becomes greater for economically vulnerable students as expected. Figure (4b) also shows that the decrease in the probability of student dropout in students enrolled in transportation programs is 0.1 pp greater for immigrant students compared to Colombian students (-4.19 pp vs -3.15 pp, respectively), and 0.77 pp greater for male students compared to female students (-3.53 pp vs -2.76 pp, respectively). These two results imply a greater effect of the transportation service as a retention strategy in immigrants and male students, compared to their counterparts (nationals and female students), respectively.

Finally, Figure (4c) shows that while the probability of dropout in students of vulnerable socioeconomic level is reduced by -3.21 pp in JEC beneficiaries, the student's probability of dropout in the population of higher stratum is reduced by -2.0 pp when JEC is supplied. Therefore, the decrease in the probability of student dropout for those who receive Complementary School Day benefits is 1.13 pp greater if the student belongs to stratum 0, 1, 2 compared to the control group. These results show the value of extracurricular activities to prevent economically vulnerable students from dropping out. The outcomes in Figured (4c) also identify better results from the Complementary School Day program for immigrants than for Colombians, as the reduction in the probability of student dropout is 1.68 pp greater for immigrant beneficiaries of JEC compared to Colombian beneficiaries of JEC (-4.44 pp vs -2.76 pp, respectively). The results for Woman coefficients find better results from the Complementary School Day program for male students compared to female students, as the reduction in the probability of dropout is 0.61 pp greater for men enrolled in the JEC program compared to women enrolled in the same program (3.28 pp vs 2.67 pp, respectively).

5. Conclusion and Discussion

This article analyzes the impact of the School Meals Program (PAE), School Transportation program (Transp), and/or Complementary School Day program (JEC) on the probability of dropping out of school in public schools from Medellin. The response variable of school dropout is modeled using the probit model. The causal effects of the three school retention programs on the predicted probabilities of students' dropout are estimated using three impact evaluation methods to obtain counterfactual groups: the Self-Selected Comparisons method, the Propensity Score Matching method, and the Endogenous Treatment-Effects method. The propensity score (in the Propensity Score Matching method) and the probability of treatment assignment (in the Endogenous Treatment-Effects method) are estimated using the heteroskedasticity probit model and the standard probit model, respectively, including regressors that reflect the eligibility criteria of beneficiaries. These criteria are followed for each program by school principals and committees, based on national regulation, and include sisben, school levels (grades), and vulnerability-associated variables (ethnicity, place of living -rural or urban, disability, and war victimization). The data are sourced from Colombia's Ministry of National Education and the Secretary of Education of Medellin, year 2019.

The results suggest that the reduction in school dropout probabilities is greater for students who have access to the retention programs by -1.0 pp (for PAE beneficiaries), by -3.17 pp (for Transportation beneficiaries), and by -2.97 pp (for Complementary School Day beneficiaries), compared to the control groups. Controlling for endogeneity, the programs with the largest impact on reducing student dropout are School Transportation and Complementary School Day. These results imply that school retention strategies are a great vehicle to continue driving educational retention by reducing financial burdens for low-income families and socially vulnerable students. The success in reducing school dropout rates driven by retention programs can serve as a lesson for other territorial entities that face challenges with the programs, including Vichada, La Guajira, and Soacha as the Unit of Meals to Learn has highlighted. The predicted probability of student dropout falls, on average, by -7.14 pp for students who are beneficiaries of all three programs simultaneously.

Sources of heterogeneity are seen regarding the effects of each school retention strategy on the probability of student dropout. At the 1 % significance level, it was found that the decrease in the probability of school dropout by students of Strata 0,1,2 is greater than the reduction of dropout probabilities by students of superior Strata (the counterfactual group) by 0.87 pp, 1.71 pp, and 1.13 pp, as they receive the benefits of PAE, School Transportation program, or Complementary School Day program, respectively. These outcomes show the effectiveness of school retention programs, not just to lower the overall students' probability of dropout, but also to balance dropout rates between economically vulnerable and nonvulnerable students; a matter that will affect the students' economic opportunities in the long run.

The Average Treatment Effect (ate) of the PAE, School Transport program, and Complementary School Day program on the reduction of dropout probabilities are found to be lower in Colombians compared to immigrants (mainly from Venezuela). The difference in the reduction of the probabilities of dropping out between these two subgroups (favoring immigrants) is 4.88 pp in PAE, 1.33 pp in Transp, and 1.68 in JEC.

The effects of school retention programs by sex show that the ate of PAE, Transp, and JEC on the probability of school dropout is greater for male students compared to female students by 0.25 pp, 0.77 pp, and 0.61 pp, respectively. The heterogeneous effects of school retention programs on the likelihood of dropping out favoring some subgroups (male immigrant and male students) should cast attention on education authorities in Medellin, who may examine whether the outcomes are as expected.

A limitation of this research is the impossibility of using a more correct variable for the students' socioeconomic level, such as income, due to missing data in simat records. Future research may include other variables associated with student dropout, including the parents' educational level and history of psychoactive substance use, among other variables, if other external data sources allow so. Finally, as the Complementary School Day's second operator is Comfenalco (which provides services for more students), it may be reasonable to think that the estimation of this program's effect on the decrease in student dropout is underestimated.

Future research endeavors may analyze the effects of strategies that are focused on overaged students and repeaters on students' dropout probabilities. These include "Aceleración del Aprendizaje" (Accelerated Learning) in elementary school and "Caminar en Secundaria" (Walking through High School), which seek to even out students who are lagging after having repeated several times, who may be thus at a higher risk of dropping out of school, according to the results of this research.

References

Abril, E., Román, R., Cubillas, M. J., & Moreno, I. (2008). ¿Deserción o autoexclusión? Un análisis de las causas de abandono escolar en estudiantes de educación media superior en Sonora, México. [Dropout or Self-Exclusion? An Analysis of the Causes of School Dropout among High School Students in Sonora, Mexico]. https://redie.uabc.mx/redie/article/view/183/319

Alcaldía de Medellín (2014). Acuerdo 50 de 2014. Gaceta Oficial N°4280. https://www.medellin.gov.co/irj/go/km/docs/pccdesign/SubportaldelCiudadano_2/PlandeDesarrollo_0_15/Publicaciones/Shared%20Content/GACETA%20OFICIAL/2015/Gaceta%204280/ACUERDO%20050%20DE%202014.pdf

Archambault, I., Janosz, M., Olivier, E., & Dupéré, V. (2022). Student engagement and school dropout: Theories, evidence, and future directions. In Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 331-355). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Barragán, S. P., & Lozano, O. L. (2022). Explanatory Variables of Dropout in Colombian Public Education: Evolution Limited to Coronavirus Disease. European Journal of Educational Research, 11(1), 287-304. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.11.1.287

Brown, M. B. (1977). Algorithm AS 116: The Tetrachoric Correlation and its Asymptotic Standard Error. Applied Statistics, 26(3), 343. https://doi.org/10.2307/2346985

Caicedo, F., Gutiérrez, G., Magin, G., & Molina, M. (2021). El Programa de Alimentación Escolar como Estrategia para la Permanencia Escolar [The School Meals Program as a Strategy for School Retention].

Camacho-Murillo, A., Méndez-Beltrán, J., & Laverde-Rojas, H. (2020). The role of Science-Oriented Workers on Innovation: The Case of the Accommodation Industry in Colombia (Working Document No 66/2020). Universidad Externado de Colombia).

Cardona, M., Montes, I. C., Vásquez, J. J., Villegas, M. N., & Brito, T. (2007). Capital humano: una mirada desde la educación y la experiencia laboral [Human Capital: A View from Education and Work Experience].

Carrillo, M. M. (2014). Política social para el avance de la educación: una evaluación del Programa de estímulos PrePa Sí del distrito federal (Vol. 18) [Social Policy for the Advancement of Education: An Evaluation of the Federal District's "PrePa Sí" Stimulus Program (Vol. 18)].

Carvalho, W. L., Moreira da Cruz, R. O., Câmara, M. T., & Guilherme de Aragão, J. J. (2010). Rural School Transportation in Emerging Countries: The Brazilian Case. Research in Transportation Economics, 29(1), 401-409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2010.07.051

Cespedes-Parra, J.; Camacho-Murillo, A. Digital Gap, and Academic Performance in the Covid-19 Pandemic: The Case of a Public School in Bogota. Preprints 2022, 2022110213. https://doi.org/10.20944/pre-prints202211.0213.v2

DANE (2023). Population Projections, Demographic Indicators. National Administrative Department of Statistics

De Janvry, A., Finan, F., & Sadoulet, E. (2012). Local electoral incentives and decentralized program performance. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(3), 672-685.

Espíndola, E., & León, A. (2002). La deserción escolar en América Latina: un tema prioritario para la agenda regional [School Dropout in Latin America: A Priority Issue for the Regional Agenda]. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, Vol. 30. https://doi.org/10.35362/rie300941

Espínola, V., & Claro Sturdo, J. P. (2010). Estrategias de prevención de la deserción en la Educación Secundaria: perspectiva latinoamericana [Dropout Prevention Strategies in High School Education: A Latin American Perspective]. Revista de educación, N°Extra-1, 257-280

Espinoza D., Óscar, Castillo G., Dante, González F., Luis Eduardo, & Loyola C., Javier. (2014). Factores familiares asociados a la deserción escolar en los niños y niñas mapuche: un estudio de caso [Family Factors Associated with School Dropout in Mapuche Children: A Case Study]. Estudios pedagógicos (Valdivia), 40(1), 97-112. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07052014000100006

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59-109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

García, B. (2016). Indicadores de abandono escolar temprano: un marco para la reflexión sobre estrategias de mejora [Early School Dropout Indicators: A Framework for Reflection on Improvement Strategies]. Pedagogika, 122(2), 124-140. https://doi.org/10.15823/p.2016.25

García, S., Fernández, C., & Weiss, C. C. (2013). Does lengthening the school day reduce the likelihood of early school dropout and grade repetition? Evidence from Colombia. Documento de Trabajo EGOB No 4. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2926193

Gertler, P. J., Martinez, S., Premand, P., Rawlings, L. B., & Vermeersch, C. M. (2016). Impact evaluation in practice, 2nd edition. World Bank Group and Inter-American Development Bank.

Gómez-Restrepo, C., Padilla Muñoz, A., & Rincón, C. (2016). Deserción escolar de adolescentes a partir de un estudio de corte transversal: Encuesta Nacional de Salud Mental Colombia 2015 [Adolescent School Dropout from a Cross-Sectional Study: 2015 National Mental Health Survey, Colombia]. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, 105-112.

Harvey, A. C. 1976. Estimating regression models with multiplicative heteroscedasticity. Econometrica 44: 461-465. https://doi.org/10.2307/1913974

Jiménez, M., & Jiménez, M. (2016). Efectos del programa Asignación Universal por Hijo en la deserción escolar adolescente [The Effects of the Universal Child Allowance Program on Adolescent School Dropout]. Cuadernos de Economía, 35(69), 709-752. https://doi.org/10.15446/cuad.econ.v35n69.54261

Leal, M. V., & Oliveira, M. (2022). School Transportation Program as Means to Improve Public Education in a Minor Rural Town in Northeastern Brazil. Ensaio, 30(114), 182-206. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-40362021002903093

Manzano, D. J., & Ramírez, J. R. (2012). Interrelación entre la deserción escolar y las condiciones socioeconómicas de las familias: el caso de la ciudad de Cúcuta (Colombia) [Interrelationship Between School Dropout and Family Socioeconomic Conditions: The Case of the City of Cúcuta (Colombia)], Revista de Economia del Caribe, 10.

Morales Vega, J. (2021). Deserción escolar en el marco de la Pandemia del covid-19 en Colombia [School Dropout in the Context of the covid-19 Pandemic in Colombia]. Universidad de los Andes. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/1992/55077

Murillo, A. F., & Gallón, A. F. (2018). Análisis de los determinantes socioeconómicos que influyen en la deserción escolar de la Institución Educativa Monseñor Díaz Plata en el Municipio de El Tarra, Norte de Santander [An Analysis of the Socioeconomic Decisive Factors that Influence School Dropout at the Monseñor Díaz Plata Educational Institution in the Municipality of El Tarra, Northern Santander] (master's thesis, Universidad Santo Tomás]. https://repository.usta.edu.co/

Nita, A.-M., Motoi, G., & Ilie Goga, C. (2021). School Dropout Determinants in Rural Communities: The Effect of Poverty and Family Characteristics. Revista de Cercetare Si Interventie Sociala. https://doi.org/10.33788/rcis.74.2

Pedroza, L. H., Ruiz, G., & López, A. Y. (2021). Duración de la jornada escolar y mejora del aprendizaje: Impacto del Programa Escuelas de Tiempo Completo en una entidad mexicana. [The School Day Length and Enhanced Learning: The Impact of the Full-Time Schools Program in a Mexican Entity]. Archivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas, 29(152). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.29.5679

Pérez-Arango, D., & Camacho-Murillo, A. (2022). Educación y comportamiento ambiental. Un estudio de caso [Education and Environmental Behavior. A Case Study]. Revista de Economía Institucional, 25(48), 193-213. https://doi.org/10.18601/01245996.v25n48.11

Rendón, E. (2024). La Alcaldía de Medellín inició la socialización sobre el Programa de Alimentación Escolar -PAE- en los 21 territorios del Distrito. Secretary of Education of Medellin https://www.medellin.gov.co/es/sala-de-prensa/noticias/la-alcaldia-de-medellin-inicio-la-social-izacion-sobre-el-programa-de-alimentacion-escolar-pae-en-los-21-territorios-del-distrito/

Rodríguez, D. (2021). Análisis de la deserción escolar por localidades en Bogotá [Analysis of School Dropout Rates by localities in Bogota]. (Master's thesis, Universidad Nacional de Colombia). https://repositorio.unal.edu.co/

Román, M. (2013). Factores asociados al abandono y la deserción escolar en América Latina: una mirada en conjunto [Factors Associated with School dropout and Abandonment in Latin America: An Overview]. REICE. Revista Iberoamericana Sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio En Educación, 11(2), 33-59. http://www.rinace.net/reice/numeros/arts/vol11num2/art2.pdf

Rosales, C. (2020). Impacto del Programa de Alimentación Escolar (PAE) del Ecuador en la matrícula y deserción escolar [The Impact of Ecuador's School Meals Program (PAE) on School Enrollment and Dropout] (Master thesis, Flacso Andes]. https://repositorio.flacsoandes.edu.ec/

Rosenbaum, P. & Rubin, D. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies of causal effects. Biometrika 70 (1), p. 41-55 https://doi.org/10.2307/2335942

Rute, A., & Verner, D. (2011). Factores de la deserción escolar en Brasil. El papel de la paternidad temprana, la mano de obra infantil y la pobreza [Factors of School Dropout in Brazil. The Role of Early Parenthood, Child Labor, and Poverty]. El Trimestre Económico, 75(310), 377-402. https://doi.org/10.20430/ETE.V78I310.38

SEM (2020). 2020 Management Report. Secretary of Education of Medellin.

SEM (2024). Programa de Transporte Escolar de la Secretaría de Educación de Medellín, Secretary of Education of Medellin. https://www.medellin.gov.co/es/secretaria-de-educacion/estudiantes/transporte-escolar/#:~:text=Tener%20entre%2010%20y%2028,educativas%20privadas%20becados%20al%20100%20%25.

Silvera, L. M. (2020). Diseño y validación de un modelo integrador para la medición, análisis y seguimiento de la deserción escolar en instituciones oficiales de educación básica y media del Distrito de Barranquilla y el Departamento del Atlántico [Design and Validation of an Integrative model for the measurement, Analysis and Monitoring of School Dropout in Official Elementary and Middle School Institutions in the District of Barranquilla and the Department of Atlántico] (Doctoral thesis, Universidad del Norte] https://manglar.uninorte.edu.co/

StataCorp. (2021). Statistical Software (Stata: Release 17.). College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.

StataCorp. (2023). Stata 18 Causal Inference and Treatment-Effects Estimation Reference Manual. College Station, TX: Stata Press

Tenti, E. (Coord). (2010). Estado del arte: Escolaridad primaria y jornada escolar en el contexto internacional. Estudio de casos en Europa y América Latina [State of the Art: Primary School and School Hours in the International Context. European and Latin American Case Studies]. SEP, IIPE-UNESCO- Buenos Aires Regional Headquarters.

Tovar, S. (February 2, 2024). Entre 2022 y 2023, de colegios y escuelas desertó el equivalente a la población de Pasto [The Equivalent of the Population of Pasto Dropped Out of Schools and Colleges between 2022 and 2023]. Red Mas Noticias, https://redmas.com.co/colombia/Entre-2022-y-2023-de-colegios-y-escuelas-deserto-el-equivalente-a-la-poblacion-de-Pasto-20240202-0036.html

UApA (2021). Resolución 335 de 2021sobre lineamientos técnicos-administrativos, los estándares y las condiciones mínimas del programa de alimentación escolar (PAE). Unidad Administrativa Especial de Alimentación Escolar.

Vergara, R., & Rodriguez, M. E. (2015). Políticas públicas instrumentales; la alimentación escolar como una respuesta a la deserción, análisis desde el enfoque sistémico [Instrumental Public Policies; School Meals as a Response to Dropout. An Analysis from a Systemic Approach]. Quaestiones Disputatae, 5(16), 176-189.

Wooldridge, J. (2010). Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: mit Press.

Wooldridge, J. (2020). Introduction to Econometrics: A Modern Approach, 7th edition, Cengage.

Appendix A

Propensity Scores for Retention Programs

* Standard errors adjusted for clusters (based on Stratum012

Source: the

authors based on data from the men (2019)

and sem.

Bitiur, cus, sa sa volupit as excestiuntur aspidundaese expliqui odioris dolest velestius alitas di coneceperae solor aut ad magnis maio. Dic tem ius maxim as rerum corro voluptata sum aut ipitas modia alitas ventis alia voluptaes etur serchil es doluptibus con por amus cus illanis quo odit mint explame nimus, sed qui qui sequatur moloreri berionsequas nobis dios eum sunt ma volum volupid quatur, simillorum dolupta volorro et estis ates si is quatio quam re volecabo. Ut laces ius.

Onsenim aximagn imincidis illupta temoluptus etus, expersp eratqui volorum hitae. Nequae pliquae stemodignis soleni omnimincto modis cuptaquiae. Enesto occabor ioresed entusae est molupta tiatet dem ratiam rem quid mos doloriosa et velecaerum estotat iorrovit autas ant et dolores aut lant veligendebit la volori blab ilignimposam sum ipsum quam ex eat minciat que rempores quate ma con et autem quis es voloreheni dest, nonse et aut quam vero mo is atur, voluptatis maios sum ipita doloriasped et ullorias nonsequosa quia aut fuga. Et vel magnatur arum qui ut ab il maios est vende ab is voles arum quibus.

Architium rectia non conseque volupti auditiosam quae endebis eumquis dus, si conecti nitaspel ent quaeresequas dit dolori ipient fugit mo dit liqui utenem eosae rescid earum quam quidel maionsequi beat ius ipiet aut es sedit, omnit quos as expernatur, sedis aut quia si consenimpore moluptatibus etur, sit ab in exces culles as ad est inciundio. Gent eum faccus et ligentia eum adi cumquatis arum et aut ut oditesenda nonsequam nis ex et et voluptio doloremqui aut res eum que simagni maximus.